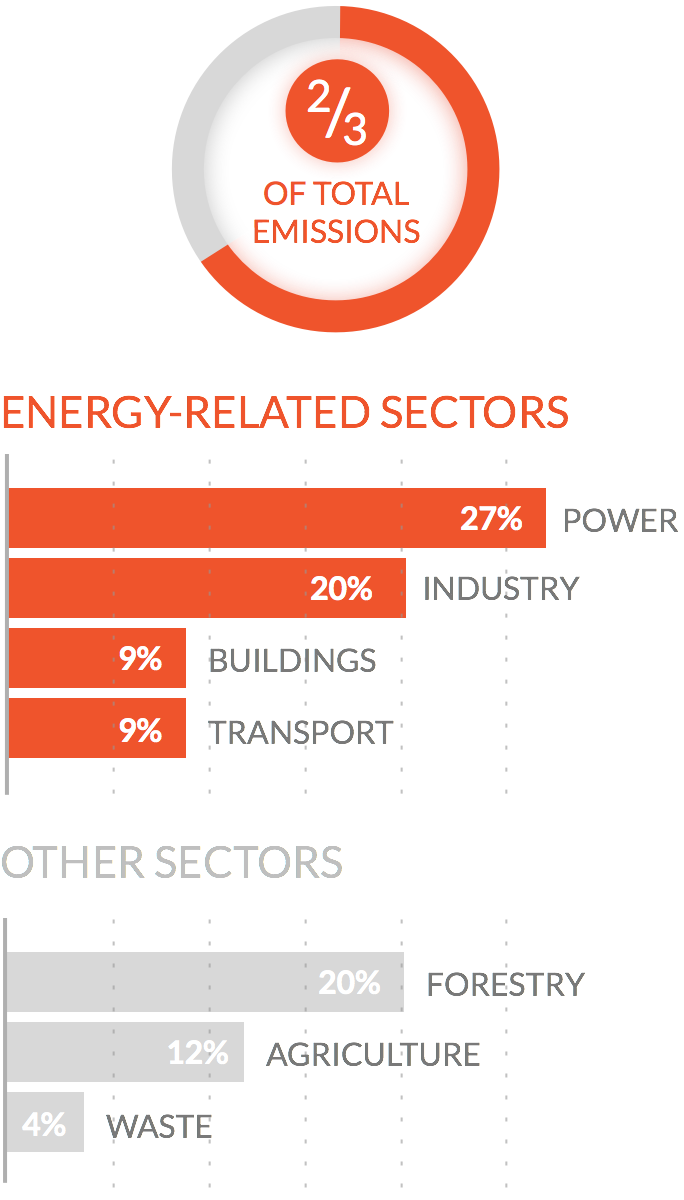

To keep economies growing and avoid dangerous climate change, the world will need to transition to a low-carbon energy system. The question on the minds of many is: will this transition hurt the economy and the financial system? Analysis shows that this does not have to be the case.

The net cost or benefit of a low-carbon energy transition will depend on governments

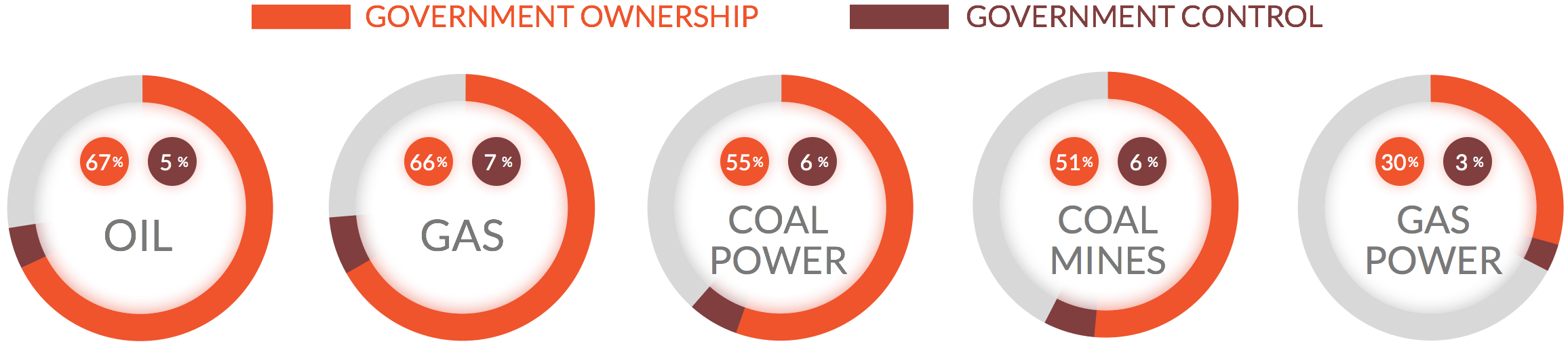

Governments own over half of global fossil fuel production and control as much as 70% of oil and gas production through companies that are wholly or majority owned by governments.

Because governments control much of the policy that may lead to stranding, they can limit the impact of asset stranding and, in many cases, create financial benefits.

What it Costs Depends on How it's Done

There are two transitions within the energy sector that are important: The transition to low-carbon electricity and the transition to low-carbon transport. Let's take a look at the transition to low-carbon electricity first.

The Transition to Low-Carbon Electricity Frees up as Much as $1.8 Trillion of Investment Capacity

Renewable energy has significantly lower operational costs compared to the high ongoing expenses of coal and gas extraction and transportation. Though capital costs are higher for renewables, the net result is still up to $1.8 trillion in increased investment capacity, creating opportunities for growth and lower costs that could reverberate across the economy.

The Transition to Low-Carbon Transport Can Also Benefit the Economy, with the Right Policies

The same policy affects producers, consumers, and governments differently. The net effect on global investment capacity could be positive or negative.

For example, in the transition to low-carbon transport, relying only on tax-based, demand reduction policies could result in a net decrease in global investment capacity.

…while relying on innovation could result in a net increase in global investment capacity.

Since relying only on innovation is uncertain, a combination of demand-reduction and innovation policies provides the most promising approach to achieve a net financial benefit.

Governments Can Benefit Even If They Act Alone

REGION Select a Region:

Regions that consume more oil than they produce can act independently of net oil producers and still enjoy almost all of the benefits of the transition to low-carbon transport. For example, if the U.S., Europe, China, India, and other oil importers were all to institute policies to reduce demand for oil, these countries could still achieve 80% of the target reduction in oil usage to keep from dangerous global warming, and receive 95% of the financial benefit they could see with global action. If these net consumers acted, net oil producing countries would benefit from reducing their consumption as well. Innovation would have an equally important cross-border impact.

Governments would do well to focus on the transition away from coal, which is the most cost-effective path to a low-carbon economy.

The global community can achieve approximately 80% of necessary carbon reductions by transitioning away from coal for 12% of global economic value at risk. In the power sector, the U.S. and EU are already on track for a transition with minimal economic value loss; China and India need alternatives to new coal plants to minimize the cost of transition to a low-carbon economy.

In the U.S. and EU, by Retiring Plants on Schedule, and Halting New Development, Future Losses Will Be Minimal.

The U.S. and EU can reduce their coal consumption with minimal loss in asset value, simply by letting their 40 and 60-year-old power plants retire at the end of their natural lives rather than refurbishing them and reducing annual hours of operation for existing plants. With the right market design (one that places a higher value on flexible power), existing plants can remain just as profitable.

Delaying Policy Action Can Markedly Increase Stranding Costs

To stay below a 450 ppm limit on CO2 emissions, many developing countries need to meet their growing energy needs without building additional coal-fired power plants. Additional coal development will result in loss of asset value. Finding an alternative to coal-fired power generation for developing countries must be a priority.

Our analysis is based on assets and investments in operation as of 2014. Delaying policy action or continuing with uncertain policy creates the risk that more investments will be made, increasing potential asset value loss in the future. Clear signals will ensure that the right investments continue at a reasonable cost while investments that are at risk of value loss are avoided.

Policies and financial innovation can help ensure the benefits of transition by reducing financing costs of low-carbon energy.

Inefficient financing methods add to the cost of renewable energy in both developed and emerging economies. There is a huge opportunity for policy to reduce financing costs and thereby reduce the costs of renewable energy.

In Emerging Economies, Achieving Low-Cost, Longer-Term Loans Will Have a Large Impact

In emerging economies with high debt costs, concessional, long-tenor debt could provide significant support for renewable energy projects at 30% less cost to governments.

In the U.S. and EU, Improving Financing with Business Model Innovation and New Financial Instruments Can Lower the Cost of Renewable Projects by Close to 20%

In the U.S. and EU, investment vehicles such as YieldCos that can efficiently channel low-cost institutional investment into low-carbon energy infrastructure have the potential to reduce the cost of low-carbon power by 20%.