Indonesia’s economy has seen rapid growth in recent decades, largely driven by natural resource extraction and land-based commodity production. Coal mining has featured prominently. The District of Berau, in East Kalimantan, is a case in point. In Berau, the mining sector regularly contributes more than 60% to Berau’s Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) and coal royalties contribute about a quarter of the district government’s overall revenue.

However, this dependence on coal has made Berau’s fiscal conditions fragile, with lower coal prices shocking the economy into a budget deficit in 2015 and 2016. The growth rate of the coal sector has diminished in recent years and price uncertainty makes it challenging for Berau to rely solely on mining to drive development and provide fiscal stability. The government acknowledges that its focus on resource extraction is not sustainable for the long-term and is beginning to shift its attention from mining to cultivation, with an emphasis on palm oil.

Prima facie, this appears to be a good strategy. Palm oil provides promise as a substitute to a coal-based economy. Even withstanding an economic slowdown at the national level, palm oil has provided a steady economic growth and jobs to Indonesians.

This CPI study, produced as part of Project LEOPALD or Low Emissions Oil Palm Development examines whether palm oil’s potential as an economic driver will bear out for Indonesia’s goals, using Berau as an example case. We find the following:

1. With palm oil edging out other estate crops, Berau’s economy currently lacks diversity and is unsustainable

Palm oil production in Berau has grown exponentially, with both Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFB) production and Crude Palm Oil production from mills increasing by 340% from 2011-2016.

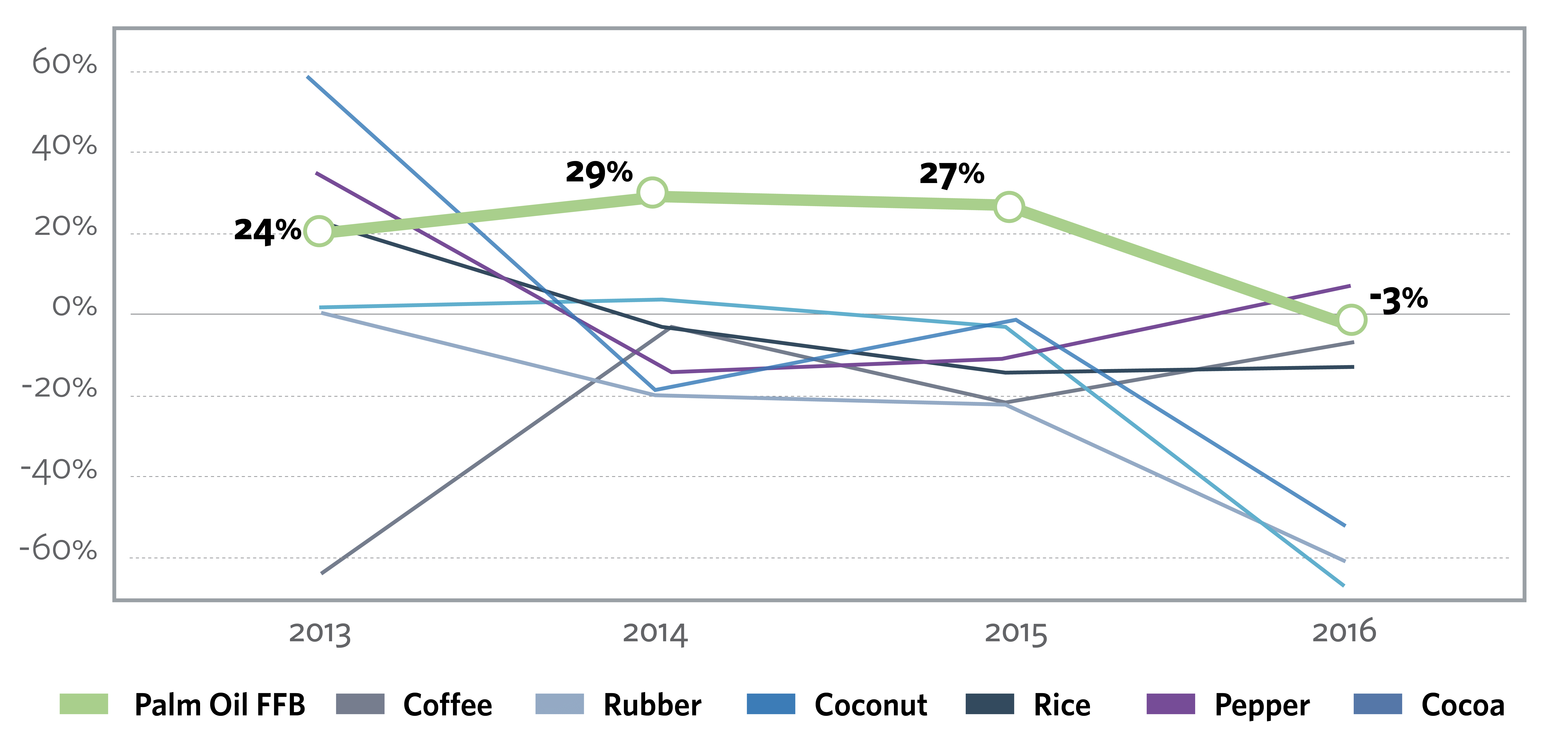

At the same time, most other estate and food crops have experienced declines in both total area and production. Coconut, rubber, and cocoa have witnessed the most prominent production declines. Pepper is starting to show positive momentum, and rice is slowly but steadily declining. See Figure ES 1. The result of these dynamics is that today, roughly 90% of the planted area and 31% of plantation land in Berau is devoted to palm oil.

Figure ES1. Year-on-year commodity production growth rates

Source: Dinas Perkebunan Kabupaten Berau 2016 and Berau in Figures 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, BPS of Berau Regency.

Source: Dinas Perkebunan Kabupaten Berau 2016 and Berau in Figures 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, BPS of Berau Regency.Financially, dependence on a single commodity exposes Berau to risks from price and demand fluctuations.

International demand for palm oil is currently slowing. Palm oil has long been subject to global criticism as many consider it one of the main drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss. The European Parliament recently called for the use of palm oil in biofuels to be banned from 2030 onward, and many of the world’s largest food and drink companies are aiming to procure only certified sustainable palm oil.

The edging out of food crops in particular is a troubling sign that Berau is shifting from a food secure region with enough staple food such as rice to self-subsist, to becoming a region increasingly reliant on imports of food crops from other regions for food security. Shifting from a focus on one extractive commodity to mono-cropping palm oil may not enable sustained economic growth. Overall, a more diversified approach is likely more promising.

2. Sustainable palm oil can be a starting point for economic growth, but needs to be hedged by a transition plan prioritizing efficiency over expansion, diversification into value-added products, and diversification into other crops

In order to hedge the risks of dependence on a single commodity, Berau can pursue several pillars of a transition plan.

First, Berau can incentivize Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certification for its existing palm oil producers. Globally, products with RSPO certification currently achieve a price premium of 1–4%. Based on the levels of production in Berau, RSPO-certification at the district level could lead to an estimated 7% increase (for a range of IDR 31—158 million/year added value) in added value per year, at the upper level. At present, though, while several palm oil companies operating in Berau are members of RSPO, few are certified, and the majority are neither members nor committed to “no deforestation.” To reduce the cost of certification, district government could become more actively involved by facilitating a single certification which declares the entire district to be deforestation-free (one of the principles of jurisdictional certification).

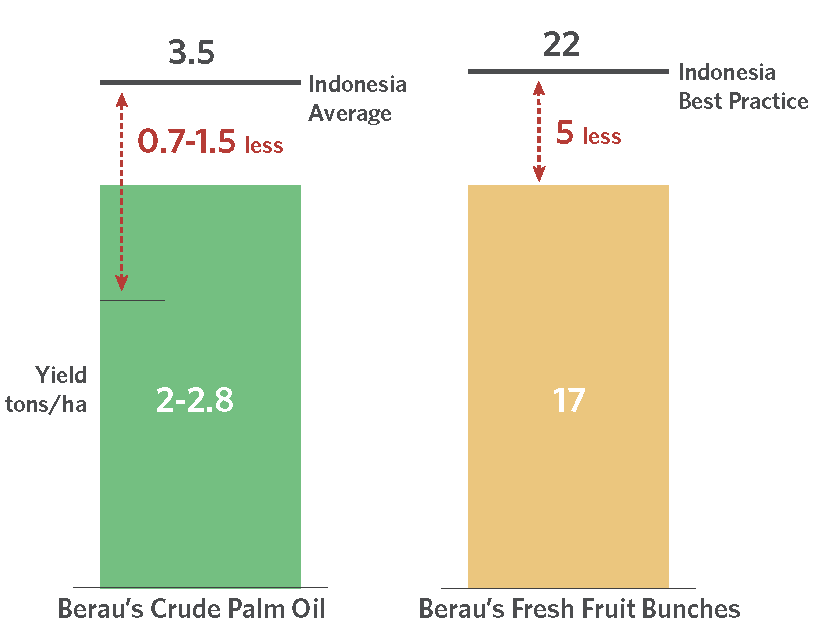

Figure ES2. Berau falls short on palm oil production

Source: CPI Calculations

Second, Berau should push palm oil plantations to become more efficient. At the moment, Berau’s FFB yield is less than 17 tons/ha, well below the national best practice of 22 tons/ha for crops of the same age range (Figure ES2). Current CPO yields in Berau are estimated at around 2.0–2.8 tons/ha while the national average in Indonesia is 3.5 tons/ha. Optimizing production and productivity within the existing plantation areas and at the mill level would allow Berau to increase its FFB yields as well as its oil yields without having to expand into new areas (Mafira, Rakhmadi, Novianti, 2018).

Third, and still within the palm oil sector, there is significant potential to expand into value-added products. There are approximately 146 types of products that could be produced by the palm oil industry in Berau. However, at present raw CPO from Berau mills are sent to eight refineries across Indonesia and Malaysia; Berau does not have a single refinery (Mafira, Rakhmadi, Novianti, 2008). This means that Berau fails to capture much of the potential added-value from processing CPO within the district.

Fourth, analysis of Berau estate crop production values per hectare between 2010 and 2014 shows that other crops may be more profitable than palm oil FFB. Cocoa and pepper show particular promise. On average, pepper production value per hectare has been more than three times palm oil FFB smallholders and nearly double palm oil FFB private companies. The estimated production value per capita of smallholder farmers lends to the same narrative: pepper is by far the most valuable estate crop on a production value basis, and cocoa is nearly equal to palm oil FFB. This suggests that encouraging farmers to explore different crops can help Berau’s overall economic diversity.

Lastly, it is important to develop the downstream industry not just for palm oil but also for other agricultural products. Recently, small home industries have shown an interest in developing consumer products from cocoa and pepper. These need to be supported and scaled. Small businesses operating in other parts of Indonesia have been successful in developing social enterprises that utilize Indonesia’s raw agricultural commodities to capture added value and drive sustainable economic growth, and these models could be replicated in Berau. Village enterprises (Badan Usaha Milik Kampung – BUMK) could be utilized to develop and/or connect with these social enterprises.

3. Berau’s fiscal health can also be supported through optimization of government revenue sources and improvements to budget allocations

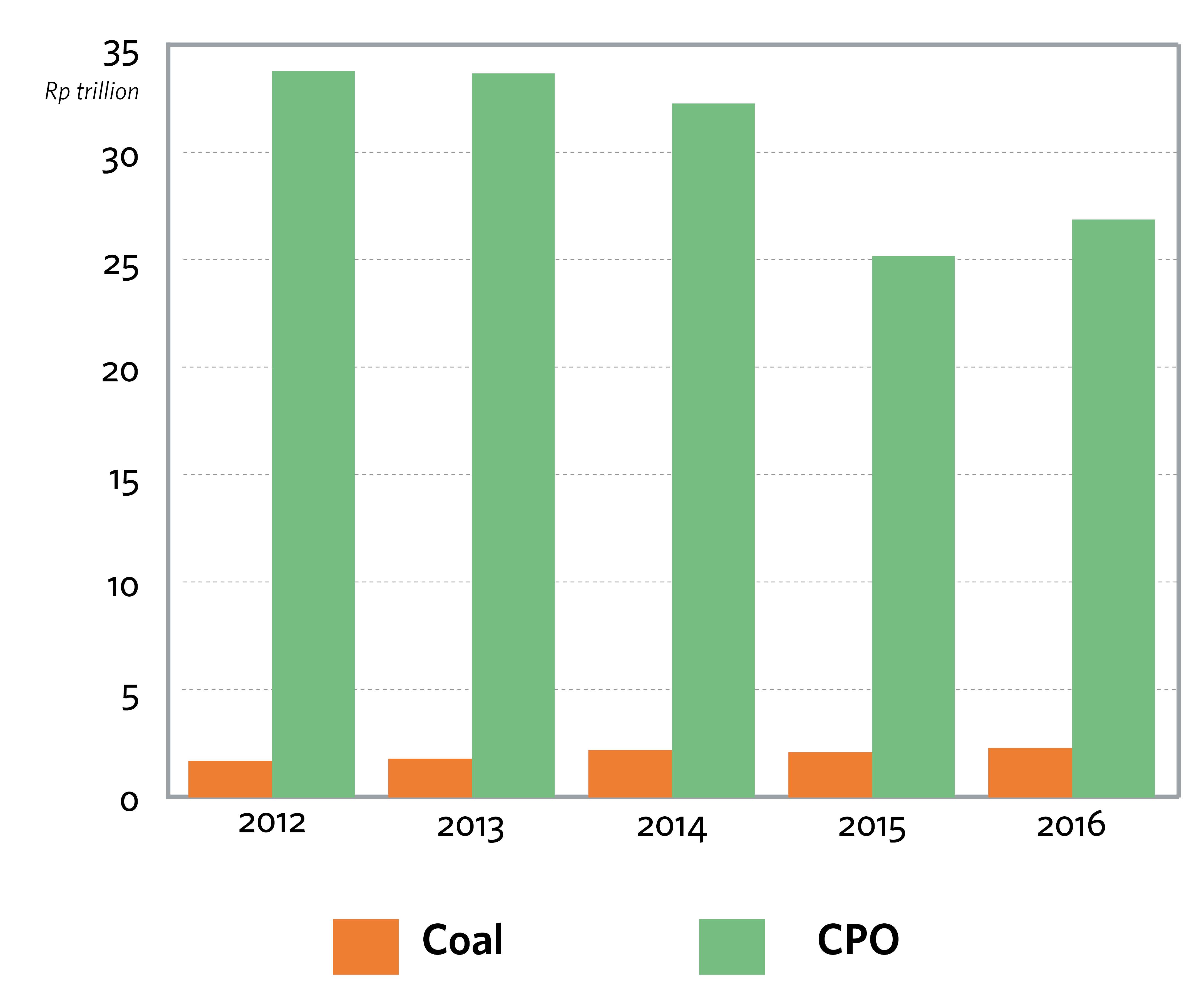

Our analysis of Berau’s fiscal data shows that Berau’s district government revenue is dominated by central government transfers with a large portion coming from revenue sharing funds related to coal mining. Palm oil growth has not translated into government revenue growth. Berau’s palm oil sector contributed an estimated IDR 559 billion (USD 42 million) to central government revenue in 2016, and only IDR 9.77 billion (USD 734,955), or 2% of their total tax contribution, went back to Berau via the Dana Bagi Hasil/DBH (IDR 1.8 billion from personal income tax and IDR 7.94 billion from the land and building tax). At the same time, palm oil does not contribute much to Berau’s own-source revenue. Approximately 80% of Berau’s own-source revenue from taxes and retribution originate from service-related industries (e.g., restaurants, hotels, healthcare, and financial markets). Despite the strong focus on agriculture and mining, currently, little revenue is secured from land licenses or permits for agriculture or mining. Figure ES2, illustrates how unrealistic it is to expect palm oil to replace coal revenues.

Figure ES3. CPO production value versus coal production value (IDR trillion)

Source: CPI Analysis, 2018

Source: CPI Analysis, 2018So, while palm oil may have direct benefits to Berau’s economy in terms of employment and improving GDRP, these benefits do not translate into government revenue that can be strategically deployed to improve overall sustainable economic growth in the district.

There are several ways in which revenue as well as spending can be improved to more strategically benefit Berau’s sustainable growth plans.

First, Berau’s own-source revenue has room for growth, as it is at the moment dominated by passive income (such as returns from deposits). This could be improved by focusing on increasing the pool of productive activities from which regional taxes could be sourced, and adds a further imperative to developing downstream industries. Specific ways in which Berau could enhance its own-source revenue include adding to the list of retributions items, such as IMB refinery permits, port permits, refining plant permits, and jurisdiction certification service to boost own-source revenue.

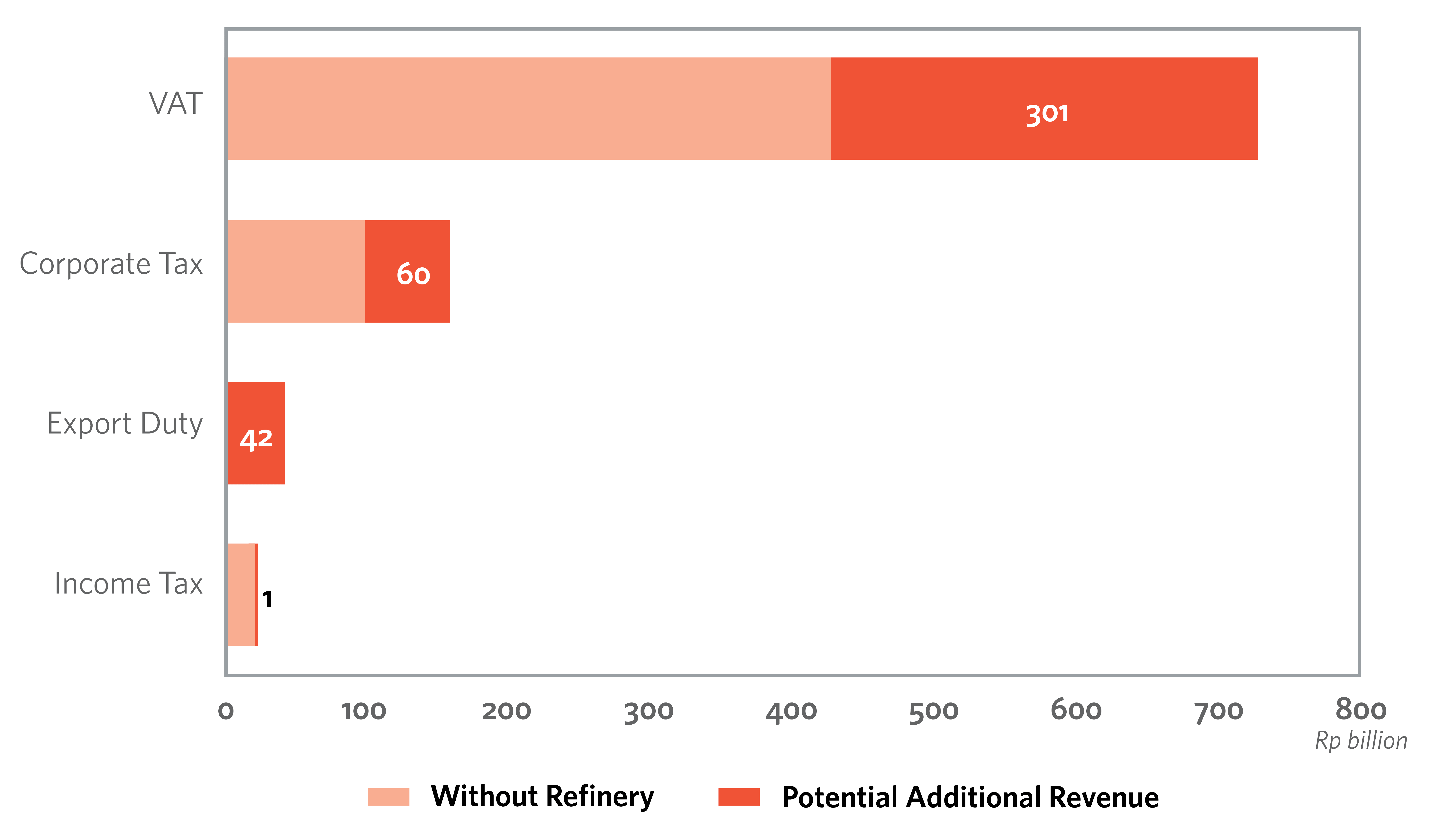

First, Berau’s own-source revenue has room for growth, as it is at the moment dominated by passive income (such as returns from deposits). This could be improved by focusing on increasing the pool of productive activities from which regional taxes could be sourced, and adds a further imperative to developing downstream industries. Specific ways in which Berau could enhance its own-source revenue include adding to the list of retributions items, such as IMB refinery permits, port permits, refining plant permits, and jurisdiction certification service to boost own-source revenue.Second, income tax could be optimized by diversifying agricultural production and down-streaming. The opening of refineries would not only create more jobs and added value for the palm oil sector in Berau, but it would also boost Berau’s government revenue. We estimate that if all CPO could be refined in Berau, this would result in a boost of approximately IDR 405 billion (USD 31 million) in national tax revenue. These additional revenues could be reinvested into infrastructure and services that support sustainable agriculture in Berau.

Figure ES5. Potential national income from palm oil refineries in Berau (IDR Billion), 2016

Source: CPI calculations, 2018

Source: CPI calculations, 2018Third, certain fund allocations could be improved by investing in business units that could leverage capital, instead of being spent on programs. For example, the Village Fund could be channeled to support village enterprises (Badan Usaha Milik Kampung – BUMK). In Berau, only 15 out of the 100 villages allocated investment for BUMK in 2017. That said, the number of BUMK nearly doubled from 26 in 2016 to 42 in 2018. The government of Berau would like to increase the number of BUMK, especially the number of BUMK structured as financial institutions, to help develop community businesses from 99 in 2017 to 584 in 2021. In Berau, 3 out of the 42 existing BUMK already conduct some form of business related to palm oil. This could be scaled up and improved by allocating more resources to developing professional BUMK.

4. Innovative fiscal transfer mechanisms need to be developed

Lastly, inter-governmental fiscal transfer mechanisms could be improved to support district economic health for districts like Berau that are prioritizing sustainability, by making transfers conditional upon the achievement of certain sustainability performance indicators.

For central-to-regional government transfers, the Special Allocation Fund (DAK) and the Regional Incentives Fund (DID) show promise as these funds already incorporate some degree of direct or indirect ecological variables. For example, the DAK allocation includes measures relating to water quality and pollution control, and a recent 2019 addition to the DID formulation actually provides incentives to local governments to manage waste more effectively, including through waste reduction and waste recycling.

For province-to-district fiscal transfers and district-to-village fiscal transfers, new fiscal transfer mechanisms which insert ecological criteria are being developed by civil society and tested in a few regions. These are:

- Ecology-based Provincial Budget Transfer (Transfer Anggaran Provinsi berbasis Ekologis – TAPE), which is a fiscal transfer mechanism between provinces to districts; and

- Ecology-based District Budget Transfer (Transfer Anggaran Kabupaten berbasis Ekologis – TAKE), which is a fiscal transfer mechanism between districts to villages.

These mechanisms envision funds to be delivered out of the Provincial Financial Aid fund (Dana Bantuan Keuangan Provinsi) using a formula for allocation that rewards the protection of forests. The indicators used to calculate the formulas are specific to forest cover and forest changes.

However, these formulas are still being discussed and are continuously being developed and modified for different provinces. The fact that the formula only considers forest cover as a variable also discriminates against districts that do not have any forest cover at all, but may have policies supporting sustainability (such as urban park initiatives or sustainable marine areas).

Next steps

Based on this analysis, we recommend specific next steps that include creating strategy for agriculture growth in Berau that prioritizes efficiency over expansion from palm oil, as well as diversification into other crops and value-added products. In addition, policymakers in Berau should encourage national-level dialogue regarding the allocation formulas for central-to-regional fiscal transfer mechanisms (e.g., DAU, DAK, DBH, DID, and the Village Fund) as well as taking small adjustments to other mechanisms to better reward and incentivize sustainable land management, setting the District up for longer-term fiscal and economic health.

In following studies, CPI will take a closer look at ecological fiscal transfer mechanisms learning from the TAPE and TAKE initiatives. Follow up studies will delve deeper into what the incentives formula might be for these transfer instruments, and how to deploy them effectively.