Transforming Indonesia’s energy sector is becoming increasingly important to achieve the country’s climate goals. According to the country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement, Indonesia seeks to reduce 834 MT CO2 emissions by 2030, 38% of which will come from reduced energy emissions. This is not only an ambitious target, but a significant increase in energy emissions reductions from previous climate change mitigation commitments.

These targets will ultimately require increased use of clean energy for power generation, and indeed, Indonesia seeks to achieve 23% renewable share in its primary energy mix by 2025. The current share of renewable energy, however, is less than 8%. This means that Indonesia will need to quickly pick up the pace if it is to achieve these goals in the next six years. And while different sources of renewable energy in Indonesia hold great potential, none have been utilized at significant levels to-date.

In 2017, renewable energy capacity only reached 6.3 GW of the total target capacity of 45.2 GW in 2025. Finance for renewable energy generation will be a key driver to help Indonesia meet its clean energy goals. PLN, the state electricity company, estimates that the total investments needed to reach renewable energy targets is IDR 2,000 trillion, or equivalent to USD 154 billion (PLN, 2016). For power generation alone, investment needs amount to IDR 1,400 trillion, or an average of IDR 140 trillion per year. To meet this target, the Government of Indonesia needs to attract other sources of finance, particularly from private actors.

Blended finance instruments, which make use of public and/or philanthropic funds to mobilize multiples of additional private capital (Tonkonogy et al., 2018), offer promising finance structuring solutions to address the risks and barriers to clean energy investment. Around the world, blended finance offers more than USD 1 trillion in investment opportunities for clean energy.

This report presents the findings from the first study in a series of reports by Climate Policy Initiative Indonesia in partnership with the Indonesian Ministry of Finance that look at national opportunities for blended finance. In particular, this study aims to understand the role of public finance instruments for clean energy and identify opportunities to optimize them to spur private investment in Indonesia. The ultimate objective is to inform Indonesia’s public resource allocation strategy so that it will address the most critical barriers to

clean energy investment and improve public capital efficiency.

The key findings of the study are as follows:

Between 2012 and 2016, public finance provided by the Government of Indonesia to support clean energy development amounted to at least IDR 12.4 trillion.

Tracked government funding between 2012 and 2016 amounted to at least IDR 2.5 trillion per year on average. The amount, directly and indirectly, was successful to the deployment of 2,140 MW of renewable energy projects across Indonesia. Of that additional power capacity, about 1,240 MW benefitted from guarantee instruments provided by the government, of which 910 MW have reached construction and operational stage (a potential 330 MW geothermal power plant is still under exploration).

Public finance instruments have different roles in supporting clean energy deployment, and some are more effective in catalyzing private investment than others.

For this study, we looked at eight public finance instruments for clean energy: budget appropriation to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR); funds transferred to regional governments under the Special Allocation Fund for Physical Development; fiscal incentives; guarantees; capital injection to state-owned enterprises; finance intermediation; viability gap funding; and feed-in tariffs.

Our assessment based on the finance provided in the period of 2012-2016 indicates that guarantees and capital injections to state-owned enterprise have the highest impact for leveraging private investment.

On the other hand, budget appropriations to line ministries and fiscal transfers to regional governments show no direct impact to address private sector barriers to renewable energy investments. Fittingly, these instruments are typically deployed to support small-scale renewable projects in remote areas in which private investment interest is absent.

There are opportunities for public finance instruments to further address financing barriers, thereby helping unlock private capital and growing the clean energy market in Indonesia.

There are several main finance barriers in Indonesia that have prevented growth in private investment in clean energy, and which public finance instruments could help to address. These include:

- High financing costs: Indonesia’s persistently high interest rate pose a significant challenge for developers looking to raise finance that allows them to meet their target financial returns.

- Limited long-term debt funding: structural problems in Indonesia’s financial system make it difficult to raise the much-needed long-term debt finance for clean energy development.

- Inefficient policy frameworks skewing risk-return profile: inefficient tariff design skews the risk-return profile of clean energy projects, and hence, becomes challenging to put together a bankable project.

- Financial sector’s risk aversion: the local financial sector’s inexperience with the clean energy sector and its reluctance to provide funding in a project finance scheme may increase the perception of risk when developing clean energy projects.

These barriers are spread across the life cycle of clean energy projects, making the case for more strategic use of public finance instruments to accelerate private participation in clean energy.

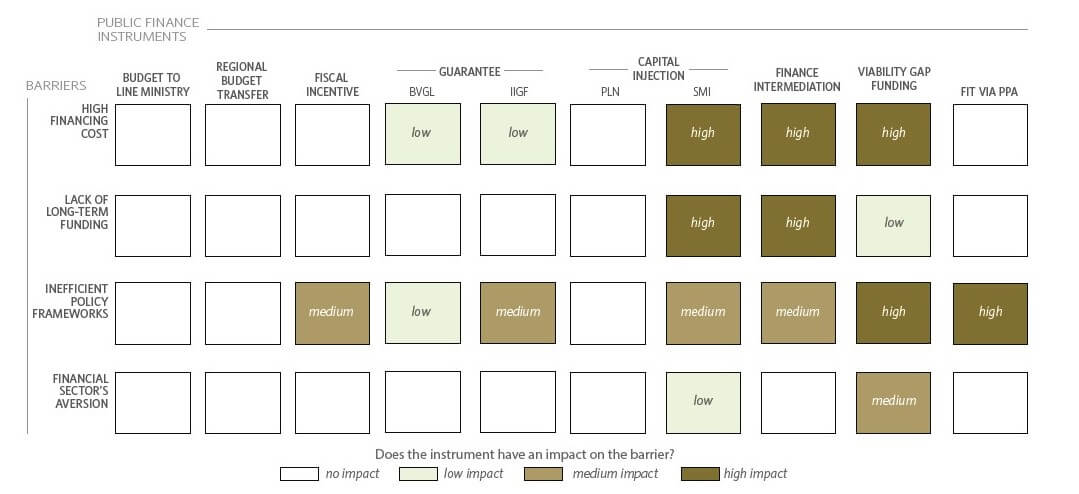

Figure 1 summarizes which public finance instruments have the most potential for addressing each financing barrier.

Fiscal incentives have good potential to improve the risk-return profile of medium-to-large scale renewable energy projects. A lower tax rate or deferred tax expenses can both directly lower generation costs and improve the risk-return profile for the project developer.

Guarantee instruments channeled through business viability guarantee letter (BVGL) and Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF) primarily focus on public sector performance, BVGL is key to guarantee PLN’s business viability and its ability to fulfill its financial obligation, both as an off-taker and borrower. IIGF covers political and public-sector performance risk in infrastructure projects under a Public Private Partnership (PPP) scheme. The coverage of risks by these instruments, which so far are still limited, have the potential to be expanded.

The government’s capital injection to PLN (state electricity company) and SMI (local development financial institution) are critical to strengthen the financial foundations of these public companies but have different impacts in terms of addressing barriers to private investment. Capital injection to PLN provides a more minor impact as most power plants developed by PLN are wholly-owned by PLN. In contrast, capital injections to SMI have high impact potential because, as a quasi development financial institution, SMI has the capacity to blend capital provided by the government with external sources of capital and the flexibility to develop financial instruments to meet the needs of renewable energy projects.

Finance intermediation also has high potential to address many private sector financing challenges, particularly if channeled through domestic public financial institutions, like SMI and its subsidiary, Indonesia Infrastructure Finance. These instruments typically channel funds from multilateral organizations which, through their excellent credit rating, have the ability to raise and provide low-cost funding with more flexible terms compared to what the recipients would be able to get in the financial market.

Viability Gap Funding (VGF) has high potential application in addressing high financing cost and in improving the risk-return profile of large-scale projects but so far it has not been provided for clean energy projects. VGF, typically in the form of grant support that does not require financial return, is provided to support infrastructure projects that are economically and technically feasible but lack commercial viability. VGF is available only to projects developed under PPP scheme, and hence, typically only to large-scale projects.

Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) has high potential in improving the risk-return profile of renewable energy projects. FiT influences the only source of revenue for renewable energy project financiers. FiT is regulated by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources and implemented through Power Purchase Agreement between PLN and Independent Power Producers.

Recommendations

Our recommendations for more optimized public finance to leverage private clean energy investment are as follows:

Provide sufficient revenue support

For renewable energy developers and financiers, proceeds from electricity sales to PLN are the only source of revenue to pay interest, repay debt, and generate returns. This means that the financial viability of a renewable energy project will be very dependent on the tariff at which IPPs are able to obtain. Under the current tariff framework, many renewable energy projects are deemed not viable due to insufficient revenue support as the technologies are still more expensive than fossil fuel alternatives in Indonesia. Therefore, tariff for renewable energy projects need to be adjusted and designed to reflect the costs of the technologies, and independent of local generation costs, complemented by cost reduction strategy in the long-run. Having a competitive tender process for awarding renewable energy projects and accessing finance at competitive terms from international sources are opportunities to reduce costs in the short-to-medium term.

Expand the role of local development financial institutions

Finance channeled through a public financial intermediary provides the highest opportunity for addressing key private investment barriers in clean energy projects in Indonesia. A local DFI, like SMI, is well positioned to assume the role as a financial intermediary between the public and private sector. As a state-owned enterprise, SMI considers both development objectives and financial return. This allows SMI to bridge financing gaps in certain sectors until they reach a stage where full market-based solutions exist. With a strong capital base from the government and networks with international donors and DFIs, SMI can source funding with competitive terms and raise debt financing in the financial market at a lower rate than their private sector peers.

Direct public finance to address critical early-stage project development risks

Public finance is more effective when directed to address the most critical risks throughout the project life cycle. The risk profile of each phase of a clean energy project varies and risks typically decrease as projects move towards operation phase. Our analysis indicates that de-risking commercial risks have more impact to reducing project costs than de-risking political risks. While the importance of instruments in mitigating political and public-sector performance risks should not be underestimated, our outreach suggests that investors have become more comfortable in dealing with these risks. For example, the need for Business Viability Guarantee Letter is not as crucial as it was in the past as investors have become more accustomed to dealing with the state-owned off-taker and, in consequence, their perception of the risk has also improved.

Expand guarantee coverage and increase focus on climate-related projects

Expanding the coverage of guarantee instruments could help increase their visibility and reach a wider range of investors. Increasing the supply of guarantees is useful for investors as they can choose the products most suited to their needs. This means investors do not have to pay for coverage of risks they are already comfortable with.

Furthermore, increased supply of guarantee products would be more effective if underpinned by specific objectives. A mandate to increase the use of guarantee for climate-related projects could also help align the interests between policy makers and guarantee providers, and hence, improve utilization. Having specific objectives and increasing the transparency of guarantee instruments in many instances proves to have positive impacts on utilization (CPI, 2013).