Infrastructure development in Brazil repeatedly presents systemic flaws that fail to prevent poor quality projects from moving forward. This often results in projects with low returns for society or, occasionally, in the abandonment of projects altogether. The implementation of a pre-feasibility analysis at an earlier stage of the project life cycle may provide means to ensure more robust projects that reduce socio-environmental risks associated with their development.

Infrastructure projects mature through various stages of studies and public decisions. In particular, Feasibility Studies (Estudos de Viabilidade Técnica, Econômica e Ambiental – EVTEA) and the Environmental Impact Assessment (Estudo de Impacto Ambiental – EIA) analyze and assess the socio-environmental feasibility of projects. More robust and effective studies lower the probability of projects harming the environment, as well as work to ensure that infeasible or low feasibility projects do not reach a stage of near irreversibility. Recently, the Minister of Infrastructure acknowledged that environmental studies in Brazil are of low quality and indicated a need to review their elaboration procedures.[1]

The New Bidding Law[2] passed by Congress in April 2021 offers a unique opportunity to anticipate issues and address risks associated with infrastructure development that are currently discussed only during EVTEA or environmental licensing, through additional regulation of the rules dealing with the so-called preliminary technical studies. This additional regulation would allow infrastructure projects to reach the implementation phase more robustly and with higher quality, reducing the risk of legal litigation and increasing investment security.

Since the recently passed New Bidding Law changes the planning of infrastructure projects and complements, in subsidiary fashion, the Concessions and Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) laws,[3] changes in the planning and feasibility phases should also encompass new projects subject to the concession and PPP models, which currently govern most major infrastructure projects in Brazil.

In this analysis, researchers from Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-Rio) analyze the new law and provide recommendations for future regulatory decrees that would further strengthen the planning process and reduce the negative socio-environmental impacts of infrastructure projects.

HIGHLIGHTS

• By prescribing preliminary technical studies, the New Bidding Law introduces a new stage in the life cycle of infrastructure projects capable of strengthening planning and ensuring the implementation of higher quality projects.

• A pre-feasibility analysis, as proposed by CPI/PUC-Rio,[4] would implement an earlier socio-environmental analysis and structure the preparatory phase of the bidding process for infrastructure projects, by liaising and sequencing EVTEA, EIA, and environmental licensing.

• The pre-feasibility analysis would also increase the chances of obtaining environmental licenses and reduce project interruptions, while also preventing infeasible or low-feasibility projects from reaching the bidding phase, only to then be excluded, either by governmental decisions or lack of bidding proposals.

• The new law takes steps to improve infrastructure projects and prevent negative socio-environmental impacts by requiring an assessment of the entire preparatory phase by the courts of accounts and the legal advisory bodies of the Public Administration.

• While the new law takes steps to improve transparency mechanisms associated with better understanding the socio-environmental risks associated with projects, its failure to require social participation undermines some of this progress.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE REGULATORY DECREES

• Develop specific rules that incorporate a pre-feasibility analysis into the preparatory phase of the bidding process for infrastructure projects.

• Require the Public Administration to consolidate and release the following documents from the preparatory phase of the bidding process for infrastructure projects on a single official website: preliminary technical studies, EVTEA, the pre-feasibility analysis conducted by independent commissions, engineering studies, and the assessment of the preparatory phase by legal advisory bodies.

PRELIMINARY TECHNICAL STUDIES AS A NEW STAGE OF PLANNING

Preliminary technical studies were already mentioned in the bidding law previously in effect as a basis for the preparation of engineering studies and as a document capable of ensuring the feasibility of projects and the adequate treatment of their environmental impacts.[5] However, the previous law did not detail the content of these studies.[6]

The New Bidding Law, on the other hand, innovates by addressing the preliminary technical studies in a much more detailed way, without, however, seeming to treat them as equivalent to the EVTEA,[7] in view of referring only to the technical and economic feasibility of the contracting.[8] The analysis of social and environmental issues, an inherent aspect of EVTEA in infrastructure projects, is not a mandatory element of the studies[9] and is restricted to the mere description of possible environmental impacts and respective mitigating measures.[10] The analysis of possible social impacts is not even mentioned.

If the goal of the new law had been to establish an identity between preliminary technical studies and EVTEA, then a great opportunity to regulate them in a robust way would have been missed, considering the fragility of EVTEA and its limited ability to ensure the feasibility of projects, especially with respect to socio-environmental issues. Thus, it seems possible to consider the preliminary technical studies as a new stage of infrastructure project planning.

ANTICIPATING THE SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS IN PRELIMINARY TECHNICAL STUDIES

According to this interpretation of the New Bidding Law, the preliminary technical studies continue to open the preparatory phase of the bidding process and to form the basis for preliminary engineering studies (“anteprojetos”), engineering studies, and terms of reference.[11] The preliminary technical studies also continue to be the first step in the feasibility analysis of infrastructure projects.[12] However, this analysis must be further developed through the EVTEA and during the first stages of environmental licensing. Under this interpretation, the new law’s requirement to detail preliminary technical studies is in line with CPI/PUC-Rio’s previous proposal to introduce a pre-feasibility phase into the planning process.[13] The main objective of this phase would be to improve project selection and prioritization.

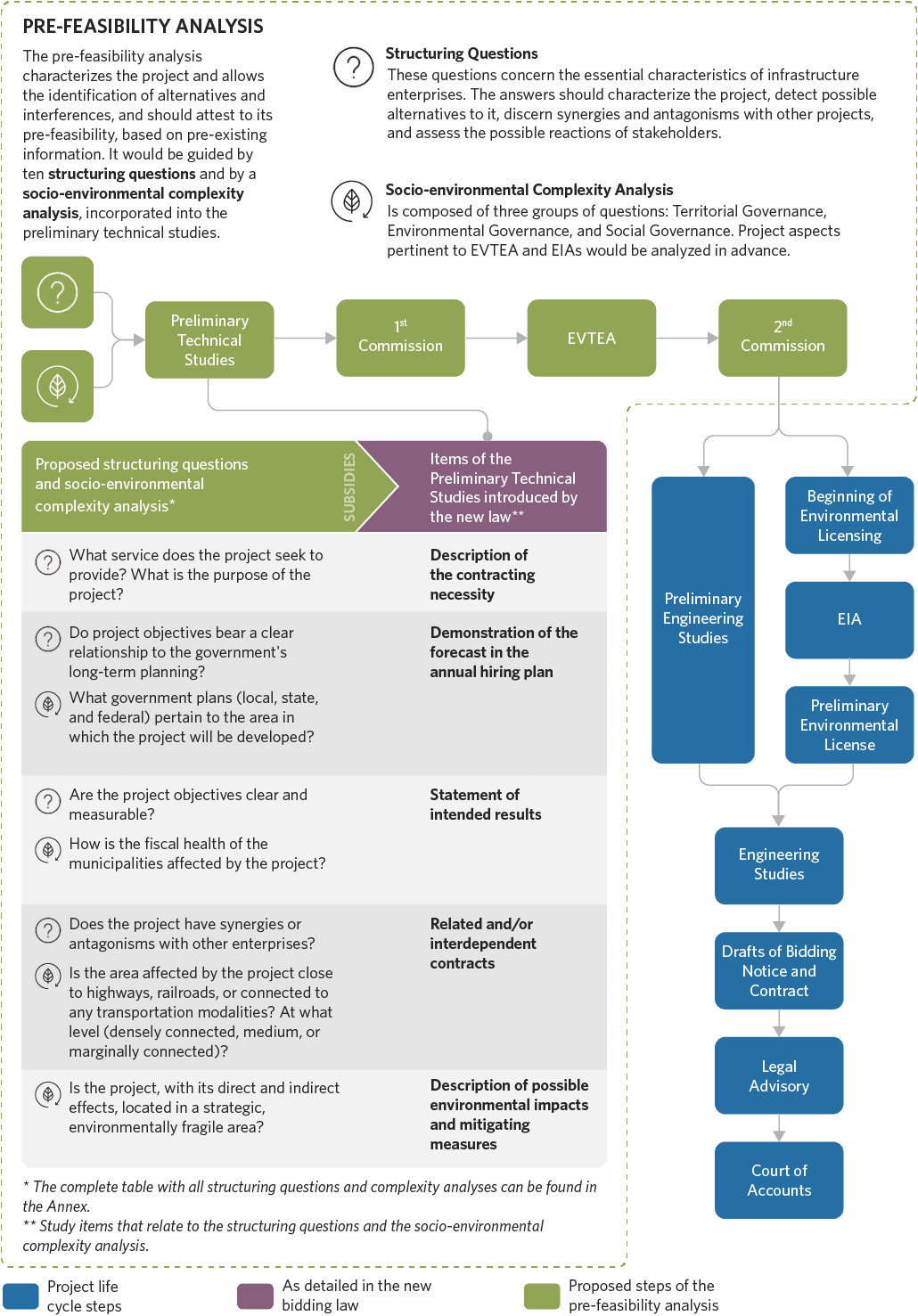

The pre-feasibility analysis proposed by CPI/PUC-Rio would be guided by 10 structuring questions about the essential features of infrastructure projects, as well as by a socio-environmental complexity assessment, in which aspects of the projects relevant to EVTEA and EIAs would be analyzed in advance. An independent commission would evaluate these characteristics and aspects and then either authorize the project or veto it from moving forward. This assessment would mark the end of the pre-feasibility analysis in the strict sense. If authorization is granted to proceed, the methodology mandates the execution of EVTEA as a reference for the project to be assessed by a separate independent commission before environmental licensing can begin. In the broad sense, the pre-feasibility analysis ends with this second assessment.

Therefore, the detailing of the preliminary technical studies, according to this reading, is more useful when mandating that the studies include a description of potential environmental impacts and mitigating measures for infrastructure projects.[14] This anticipates the environmental analysis in the project life cycle, similarly to the provisions set forth in the pre-feasibility analysis proposal, but without getting in the way of the socio-environmental analysis by the EVTEA. Other study items listed in the new law also align with CPI/PUC-Rio’s proposed structuring questions and socio-environmental complexity assessment, as evidenced by the Annex to this document.

Therefore, future decrees for the new law should introduce and regulate a pre-feasibility analysis, to anticipate not just environmental, but socio-environmental analysis, through the preliminary technical studies, and to structure the preparatory phase of the bidding process, by means of a procedural interlinking between preliminary technical studies, EVTEA, EIAs, and licensing, as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pre-Feasibility Analysis Introduced into the Preparatory Phase

Note: The order of the steps following the pre-feasibility analysis was adapted, based on the New Bidding Law, from a previous study by CPI/PUC-Rio (Chiavari, Joana, Luiza Antonaccio, and Gabriel Cozendey. Regulatory and Governance Analysis of Transportation Infrastructure Projects in the Amazon. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, forthcoming).

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio, based on analysis by CPI/PUC-Rio and Inter.B, 2021

NEED FOR ALIGNMENT BETWEEN PRELIMINARY TECHNICAL STUDIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL LICENSING

A specific provision of the New Bidding Law on environmental licensing also confirms the need for alignment between the contents of preliminary technical studies, EVTEA, EIAs, and licensing. It refers to the possibility of unilateral contract termination by the Public Administration if the environmental license causes substantial changes to the preliminary engineering studies or when obtaining such a license is impossible.[15] As made clear, preliminary engineering studies must be prepared based on preliminary technical studies.

If a license cannot be acquired or causes a substantial change to the preliminary engineering study, this means that the preliminary technical studies, the EVTEA, and the preliminary engineering study were based on mistaken assumptions refuted later in the licensing process. This can be avoided by the 10 structuring questions and the socio-environmental complexity assessment proposed by CPI/PUC-Rio, which aim to prevent infeasible projects from moving forward and provide more consistent premises for sustainable enterprises, making them less likely to be interrupted and more likely to be granted licenses.

This provision under the New Bidding Law places the obligation to obtain the license squarely on the contracted party. This possibility was contemplated,[16] in view of the procedures in place for PPP projects[17] and the Investment Partnerships Program (Programa de Parcerias de Investimentos – PPI).[18] PPP and PPI also seem to have inspired an attempt to determine that prior licensing or guidelines for environmental licensing must be obtained before the bidding notice is made, in cases when the Administration is responsible for license acquisition. However, the President of the Republic vetoed this attempt.[19]

ASSESSMENT OF THE PREPARATORY PHASE BY LEGAL ADVISORY BODIES

Under the new law, the entire preparatory phase of the bidding process must be submitted for assessment to the Administration’s legal advisory bodies.[20] Examples of such bodies include the federal Attorney General’s Office (Advocacia-Geral da União – AGU) and the state and municipal prosecutors’ offices. This provision represents progress from the previous bidding law, which used to restrict the assessments by these bodies to bidding notice drafts and the drafts of contracts, agreements, covenants, or adjustments.[21] Thus, the new law increases the scope of the assessment and enables legal advisory bodies to evaluate the soundness of preliminary technical studies and pre-feasibility analyses. In doing so, these bodies can strengthen these mechanisms to prevent the socio-environmental impacts caused by infrastructure projects.

RISK MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTIVE CONTROL BY COURTS OF ACCOUNTS

A controversial change introduced by the New Bidding Law refers to the establishment of courts of accounts as entities in charge of risk management and preventive control for bidding processes,[22] including the prevention of risks derived from socio-environmental issues.[23] The new law does not include details on how these tasks should be carried out, but they are quite commonplace in the scope of infrastructure project governance. PPI projects, for example, are subject to prior control by the Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União – TCU).[24] There is controversy because there is no explicit constitutional authorization to exercise this type of control – what some legal scholars call an “eloquent silence”: unless specifically provided for in the Constitution, the courts of accounts may not exercise prior control.[25]

The TCU justifies its preventive actions with practical reasons, such as the need to improve bidding processes or avoid project interruptions.[26] These actions are also justified by the existence of implicit powers needed for the court to operate effectively.[27] The provision in the new law is expected to placate the criticism against prior control and strengthen the TCU’s position in this controversial matter, with potential ramifications for state and municipal courts of accounts. The New Bidding Law also establishes that oversight bodies must follow the guidance provided by the TCU’s interpretation of the provisions established therein.[28] This strengthens the court’s role in unifying the interpretation of the new law.

MORE TRANSPARENCY AND LESS SOCIAL PARTICIPATION

According to a CPI/PUC-Rio assessment of federal projects for the concession of land transportation infrastructure in the Amazon, 57% of the documents and information on these projects could not be found.[29] In most cases, it is impossible to ascertain whether a missing document or information is unavailable or simply does not exist. Situations like this usually add insecurity when inspection bodies, investors, and civil society evaluate the socio-environmental risks associated with infrastructure projects.

As such, the New Bidding Law was justified in creating a single official website, which must contain all bidding notices, draft contracts, contracts, terms of reference, preliminary engineering projects, related annexes, and reports on the achievement of contract objectives.[30] The law was also correct in referring to[31] the need to comply with the Freedom of Information Act.[32]

However, it is important for future decrees regulating this new law to create a specific obligation to make the following documents from the preparatory phase of the bidding process for infrastructure projects available on the website: preliminary technical studies, EVTEA, the pre-feasibility analyses conducted by independent commissions, engineering studies, and the assessments of the preparatory phase by legal advisory bodies. A generic obligation to make such annexes available is already mandated by the new law.

In terms of social participation, the New Bidding Law has backtracked by simply encouraging – rather than mandating – the Administration to summon consultations or public hearings prior to bidding.[33] At the very least, it should have kept the requirement to hold hearings for projects budgeted above a certain threshold, as was the case in the previous bidding law.[34] This setback in the new law undermines its efforts to increase transparency.

PRIORITY GIVEN TO ENVIRONMENTAL LICENSING OF CONSTRUCTION WORKS

The New Bidding Law establishes priority for environmental licensing of construction works.[35] Like other innovations introduced by the law, such prioritization might only be applied two years after its entry into force. The priority refers only to works contracted under the new law, and the bidding law previously in effect will be revoked only at the end of the two-year period. During this time, there will be two bidding laws in effect, and the Administration may choose between either of them, for new projects.[36] A strong adherence to the new law, during this period, would mean that the Administration has already adapted to its rules, which does not seem likely. Even a two-year period seems insufficient: the government has been working to comply with the previous bidding law for almost three decades, and the challenges are evident.

NEW BIDDING LAW AND LEGISLATIVE BILL FOR A NEW CONCESSIONS LAW

Lastly, a legislative bill is currently under consideration by National Congress to create a new concessions law. The bill aligns well with this analysis, since it raises relevant points about environmental licensing and EVTEA, as detailed in a previous analysis and recommendations by CPI/PUC-Rio.[37]

Regarding licensing, there is an opportunity for this bill to establish the use of sectoral rules to determine when a preliminary environmental license must be obtained and who would be responsible for obtaining it. These measures would add legal certainty and predictability to risk allocation for infrastructure projects.

On the EVTEA front, the project can advance along three paths: it may establish a minimum set of criteria for analysis by these studies; it may mandate that EVTEA assessment and approval methods be regulated; and it may set the execution of studies as a precondition for bidding on greenfield infrastructure projects.

CONCLUSION

The New Bidding Law offers an opportunity to further minimize and prevent the negative socio-environmental impacts of infrastructure projects. For this to happen, future regulatory decrees should incorporate the pre-feasibility analysis proposal presented by CPI/PUC-Rio. This would anticipate the socio-environmental analysis, structure the preparatory phase of the bidding process, increase the chances of obtaining licenses and avoid eventual project interruption. This potential is reinforced by the innovations of the law in terms of transparency and the involvement of courts of accounts and legal advisory bodies. Setbacks in social participation, on the other hand, undermine the prevention of socio-environmental impacts.

ANNEX

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio, based on analysis by CPI/PUC-Rio and Inter.B, 2021

The authors would like to thank Luiza Antonaccio for her review and support in the conception of figures, Natalie Hoover El Rashidy and Giovanna de Miranda for revision and editing and Meyrele Nascimento, Nina Oswald Vieira, and Matheus Cannone for the graphic design work.

[1] O Estado de S. Paulo. Infraestrutura admite que estudos ambientais do governo são de baixa qualidade e revê processos. 17 February 2021. bit.ly/3f6u1vO.

[2] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[3] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 186. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[4] Chiavari, Joana, Luiza Antonaccio, Ana Cristina Barros, and Cláudio Frischtak. Ciclo de vida de projetos de infraestrutura: do planejamento à viabilidade. Criação de nova fase pode elevar a qualidade dos projetos. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2020. bit.ly/2T47kjf.

[5] Presidência da República. Lei nº 8.666. Art. 6, IX. 1993. bit.ly/3f6qfm4.

[6] The closest attempt to detailing content seems to have been to list, as the minimum contents of a “work plan”, in a decree that has already been revoked, the justification of the need to contract, the quantities contracted, and the demonstration of the results of the contracting (Presidência da República. Decreto nº 2.271. Art. 2. 1997. bit.ly/344HTQZ).

[7] In the context of the previous law, such an equivalence seemed to exist, according to the interpretation of the Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União. Acórdão nº 2.215 – Plenário. 2016. bit.ly/3462UuE).

[8] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 18, §1º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[9] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 18, §1º, XII. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[10] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 18, §2º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[11] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 6, lines XX; XXXIII, ‘b’; XXIV, ‘g’; and XXV; and Art. 18, I. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[12] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 18, § 1º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[13] Chiavari, Joana, Luiza Antonaccio, Ana Cristina Barros, and Cláudio Frischtak. Ciclo de vida de projetos de infraestrutura: do planejamento à viabilidade. Criação de nova fase pode elevar a qualidade dos projetos. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2020. bit.ly/2T47kjf.

[14] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 18, § 1º, XII. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[15] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 137, VI. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[16] “Art. 25. (…) § 5º The bidding notice may require the contracted party to: (…) I – obtain an environmental license”.

[17] Based on Art. 10, VII, of Federal Law 11.079/2004, which allows for biddings after the licensing guidelines have been set, meaning that the license acquisition may be placed under the responsibility of the contracted party: “Art. 10. Contracting of public-private partnerships will be preceded by a competitive bidding process, and the opening of the bidding process is conditioned on: (…) VII – prior environmental licensing or issuance of guidelines for the environmental licensing of the enterprise, in accordance with regulations, whenever the object of the contract so requires”.

[18] Based on Art. 6 of PPI Council Resolution 1/2016: “Art. 6. When the object of the contract requires it, the bidding process for the enterprise will be conditioned, in accordance with the applicable legislation, to the attestation of its environmental feasibility through the issuance of a Preliminary License (LP, Licença Prévia) or guidelines for environmental licensing”.

[19] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 115, § 4º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[20] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 53, caput and § 3º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[21] Presidência da República. Lei nº 8.666. Art. 38, parágrafo único. 1993. bit.ly/3f6qfm4.

[22] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 169, caput and line III. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[23] A study commissioned by CPI/PUC-Rio on preventive assessments of socio-environmental aspects of PPI projects by the Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União – TCU) found that the court looks into, for example, whether environmental obligations can influence the economic and financial balance of concession contracts. The TCU has also noted the low quality of the EVTEA conducted for these projects. (Rodrigues, Juliana Garcia Vidal. Atuação do TCU na fase interna da licitação dos projetos de privatização do PPI de rodovias e ferrovias: estudos socioambientais. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, forthcoming).

[24] Conselho do Programa de Parcerias de Investimentos. Resolução nº 1. Art. 16. 2016. bit.ly/3f8teKT.

[25] Jordão, Eduardo. “A intervenção do Tribunal de Contas da União sobre editais de licitação não publicados: controlador ou administrador?” In Tribunal de Contas da União no Direito e na Realidade, 345. São Paulo: Almedina, 2020.

[26] Jordão, Eduardo. “A intervenção do Tribunal de Contas da União sobre editais de licitação não publicados: controlador ou administrador?” In Tribunal de Contas da União no Direito e na Realidade, 353. São Paulo: Almedina, 2020.

[27] Jordão, Eduardo. “A intervenção do Tribunal de Contas da União sobre editais de licitação não publicados: controlador ou administrador?” In Tribunal de Contas da União no Direito e na Realidade, 357. São Paulo: Almedina, 2020. The Brazilian Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal – STF) has already validated this thesis (loc. cit.).

[28] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 172. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[29] Chiavari, Joana and Gabriel Cozendey. Viabilidade Ambiental de Infraestruturas de Transportes Terrestres na Amazônia Legal. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, forthcoming.

[30] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 25, § 3º; Art. 54; Art. 174, I; Art. 174, § 2º, III and V; and Art. 174, § 3º, VI, ‘d’. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm. The availability of the contract and amendments is an indispensable condition for contractual effectiveness, that is, the contract, in theory, could not be executed before this requirement is met (Art. 94).

[31] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 174, § 4º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[32] Presidência da República. Lei Federal nº 12.527. 2011. bit.ly/3hG59wJ.

[33] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 21. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[34] Presidência da República. Lei nº 8.666. Art. 39. 1993. bit.ly/3f6qfm4.

[35] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 25, § 6º. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm. The Federal Law 13.334/2016, which creates the PPI, includes a similar provision, stating that “projects qualified under the PPI will be treated as enterprises of strategic interest and will be granted national priority by all public entities in the administrative and controlling spheres at the federal, state, Federal District, and municipal levels of government ” (Art. 5).

[36] Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.133. Art. 191; Art. 193, II; and Art. 194. 2021. bit.ly/3fuxvHm.

[37] Antonaccio, Luiza, Joana Chiavari, and Gabriel Cozendey. Ajustes no projeto da nova lei de concessões podem garantir uma infraestrutura mais sustentável e de maior qualidade. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2020. bit.ly/3fArHw3.