In Brazil, deforestation is a major driver of increased carbon emissions, exacerbating the effects of climate change. In the last decade, deforestation rates in the Amazon rainforest have risen, with a sharp increase of 74% between 2018 and 2022.[1]

Reversing this trend is a priority of the Brazilian government that has pledged to achieve zero deforestation in the region by 2030.[2] To meet this goal, it will be essential to implement public policies that focus on areas of greatest impact. With this in mind, Gandour and Mourão (2022) identified the reduction of deforestation in rural setllements in the Amazon as a priority for forest protection.[3]

Rural settlements are areas designated for agrarian reform, where landless families are settled so that they can cultivate the land and have better living conditions.[4] These settlements comprise an essential part of Brazil’s strategy to promote greater equality in land distribution and social justice.[5]

Despite the importance of the rural settlements to Brazil’s agrarian reform, a significant amount of deforestation in the Amazon occurs in these areas. While they make up for just 8% of the biome, 28% of deforestation occurred in settlements between 2012 and 2022.

In this publication, researchers from Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-Rio) analyze deforestation in settlements in the Amazon between 2012 and 2022. They find that deforestation in settlements is highly concentrated and suggest priority areas for government action to combat deforestation in the Amazon.

Where to act?

In 2022, 75% of forest loss in settlements occurred in only 5% of the 2,312 settlements in the biome. This pattern is both concentrated and persistent: the same settlements have contributed to most of the deforestation from year to year.

Changing the land use patterns of this small group of settlements would have significant impacts on the preservation of the forest, both in the short and long term. In the short term, it would address the fact that these settlements have been a main driver of deforestation in recent years. For the long term, targeting these settlements would also prevent them from maintaining this role over the next decade.

How to act?

Certain policies are essential for combatting deforestation and should be applied broadly in rural settlements. These include strengthening environmental monitoring and imposing effective punishments for those responsible for deforestation. The adoption of other policies, however, can vary depending on the specific context of each settlement.

Different settlements may require different approaches from the government. Identifying the factors and actors driving forest destruction in rural settlements is a crucial step in establishing an effective intervention strategy. This will make it possible to decide on an appropriate mix of policies to complement command and control efforts for each situation.

The Amazon in Agrarian Reform

The Amazon biome contains 70% of settled areas and 63% of settlers of the land reform. The agrarian reform movement gained strength in the region during the 1970s, with the creation of colonization projects that encouraged the destruction and occupation of the forest. In 1984, the government began to create conventional settlements, primarily focused on agriculture. The late 1990s and early 2000s saw increased momentum for projects with sustainable production models that included the biome’s traditional communities as well as the extractive industries.

From the mid-2000s onwards, the environmental perspective became a central element of land reform policies in the Amazon. Guidelines were established to limit new conventional settlements to consolidated areas and to prioritize the creation of environmentally differentiated settlements.[6] These settlements focus on activities that are compatible with the forest and aim to boost conservation.[7] Between 2004 and 2012, the environmentally differentiated settlements increased from 1.7 to 12.4 million hectares. Since that time, the biome has experienced only modest expansion of any type of settlement, with a settlement growth rate of just 1% between 2012 and 2022.

The Amazon biome is currently home to 2,312 settlements, 77% of which are conventional, and 21% are environmentally differentiated. Environmentally differentiated settlements extend over larger areas, providing more hectares per family, in line with the demand for larger spaces to develop sustainable activities.

Table 1. Settlements in the Amazon Biome, 2023

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA,[8] Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA,[9] PRODES/INPE,[10] and Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019),[11] 2023

Note: Conventional settlements refer to projects in the following categories: Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento – PA) and State Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentameno Estadual – PE). Environmentally differentiated settlements refer to the following projects: Agro-extractive Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Agroextrativista – PAE), Sustainable Development Project (Projeto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável – PDS) and Forest Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Florestal – PAF). Other refers to the following projects: Joint Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Conjunto – PAC), Directed Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Dirigido – PAD), Municipal Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Municipal – PAM), Quilombola Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Quilombola – PAQ), Rapid Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Rápido – PAR), Cocoon Settlement Project (Projeto de Assentamento Casulo – PCA) and Integrated Colonization Project (Projeto Integrado de Colonização – PIC).

Profile of Deforestation in Settled Areas

Despite occupying only 8% of the Amazon, settlements accounted for 28% of all deforestation between 2012 and 2022.[12] Over this period, 5% of settlements (116 projects) were responsible for 17% of deforestation in the biome. In terms of area, this means that almost a fifth of deforestation is concentrated in just 2% of the biome (Figure 1). Thus, implementing policies aimed at these settlements presents an opportunity to reduce deforestation in the region rapidly and on a large scale.

Figure 1. Deforestation in Settled Areas in the Amazon Biome, 2012-2022

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, PRODES/INPE, and Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), 2023

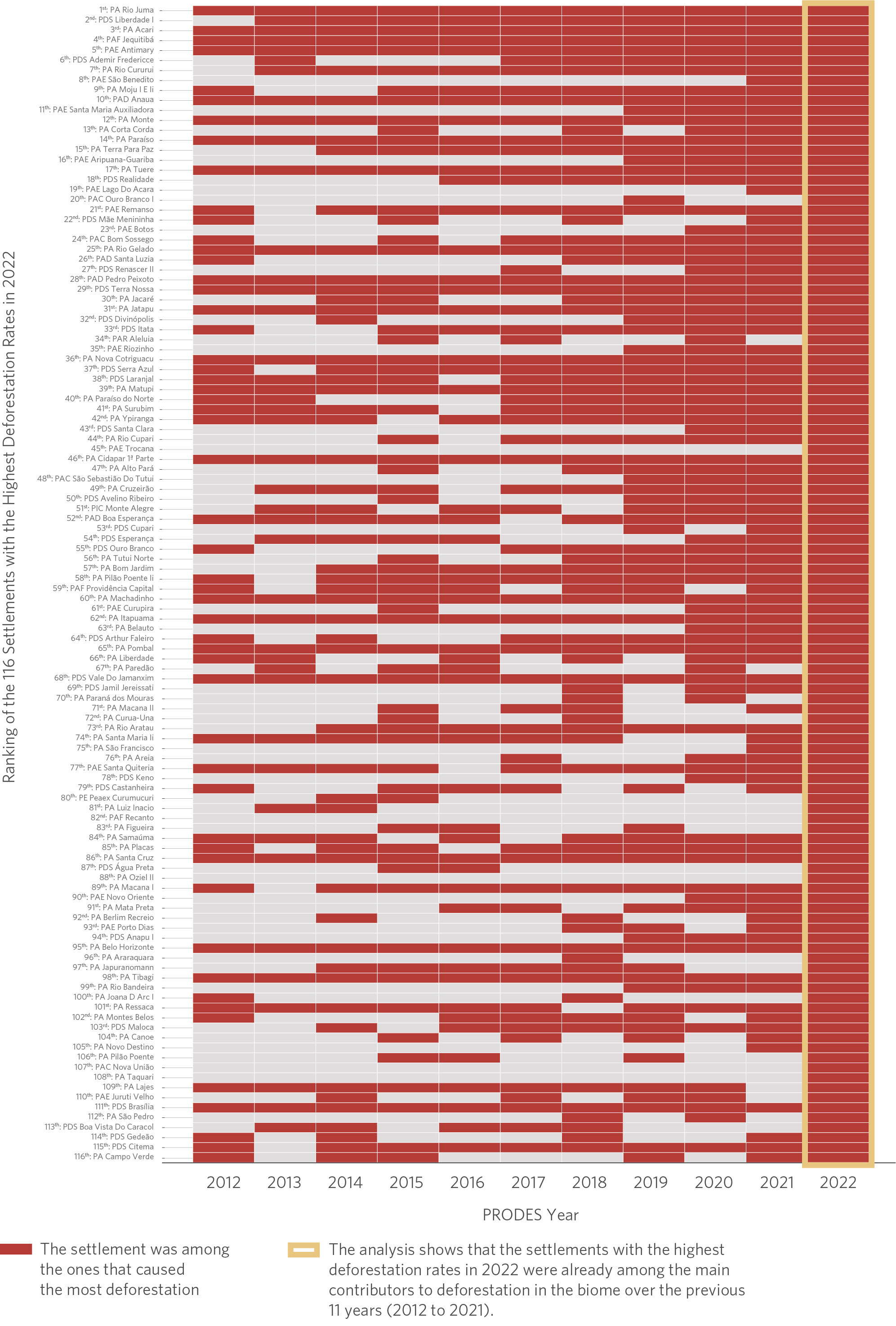

The settlements that recorded the highest rates of deforestation in the biome in 2022 were also among those where most of the deforestation happened in previous years. Figure 2 shows the pattern of deforestation over the last decade in the 116 rural settlements with the greatest amounts of deforestation in 2022. Of the 116 settlements, 23 were among the 5% where more deforestation happened throughout the entire period analyzed and 68 comprised part of this group for at least half of the period.

Figure 2. Participation in Deforestation of the 116 Settlements Responsible for the Most Deforestation in 2022 in the Amazon Biome, 2012–2022

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, PRODES/INPE, and Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), 2023

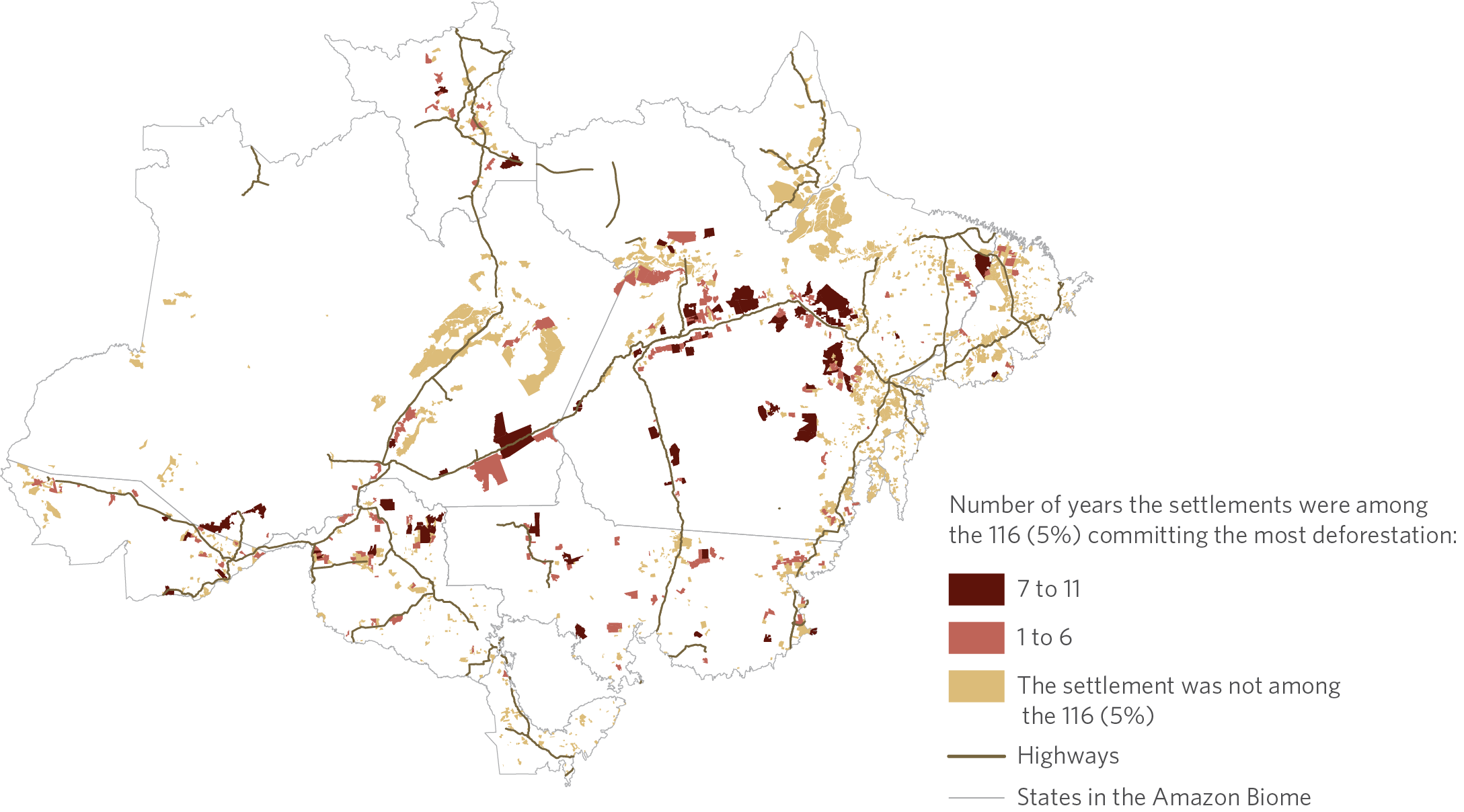

In addition to the pattern observed in the settlements with the most deforestation, there is also a spatial concentration. Figure 3 shows the spatial distribution of all settlements in the Amazon according to the number of times they were among the 116 (5%) committing the most deforestation between 2012 and 2022. Note that the settlements clearing the most forest are often concentrated in specific locations, usually close to federal highways. This pattern points to the potential for implementing policies targeting priority areas in the fight against deforestation.

Figure 3. Settlements in the Amazon Biome by Participation in Deforestation, 2012–2022

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, PRODES/INPE, and Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), and DNIT/SNV (2018),[13] 2023

It is also worth noting that the deforestation in the 116 settlements with the most deforestation is concentrated in episodes covering larger areas (Figure 4). For example, in 2022, 36% of the deforestation in these 116 settlements occurred in large-scale areas of over 100 hectares. For the other settlements, this number was only 4%. This pattern suggests a possible link between forest loss in these settlements and larger-scale agriculture activities.

Figure 4. Deforestation in Settled Areas of the Amazon Biome by Size of Deforestation Episode, 2012–2022

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, PRODES/INPE, and Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), 2023

Public policies for land use in settlements

The fight against deforestation in settled areas of the Amazon requires strategic action on the part of the government. More than 70% of deforestation in settlements occurs in municipalities classified as “under pressure” by Veríssimo et al. (2022).[14] In other words, these are municipalities that are on the Brazilian Ministry of Environment’s (Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima – MMA) list of priority municipalities, or that have deforested more than 100 km² in the last three years (Figure 5). The fight against deforestation in settlements therefore requires action in the same municipalities targeted in the national strategy.

Figure 5. Deforestation in Settled Areas of the Amazon Biome by Type of Municipality, 2012-2022

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, PRODES/INPE, Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), and Veríssimo et al. (2022), 2023

The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis – IBAMA) plays an essential role in halting deforestation in the Amazon given that most of it is illegal (95%).[15], [16] Overall, deforestation rates have increased with the weakening of IBAMA’s activities in the Amazon in recent years.[17] This also holds true for deforestation in the settlements, which has also increased (Figure 6). Reversing this trend and strengthening environmental control agencies is central to protecting the forest in the settlements.

Figure 6. Number of Fines for Infractions Against the Flora and Deforestation in Settlements, 2012-2022

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, PRODES/INPE, Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), and Fiscalização – auto de infração/IBAMA (2022),[18] 2023

While command and control efforts are fundamental, they are not enough. In addition to punishing the destruction of the forest, it is important to encourage practices that favor its conservation. The persistence of deforestation in settlements indicates that the country needs a robust framework of tools, with the aim of not only reducing but also ending deforestation.

Some lessons can be learned from the Sustainable Settlements Project.[19] This is a third sector initiative[20] financed by the Amazon Fund that was active in three settlements in Pará between 2012 and 2017, providing technical and administrative assistance to settlers.[21] The project aimed to strengthen family farming in the Amazon region by integrating agro-ecological transition, environmental preservation, and recognition of ecosystem services.[22]

As part of the program, 350 families had access to payments for environmental services (PES). PES schemes make it possible to reward rural settlers for preserving the forest, promoting their economic development in a sustainable way. Subsequent studies have shown that these families have increased their production and reduced their deforestation.[23] A result indicating that PES payments and technical assistance encourage forest conservation and promote more productive and sustainable farming.

The region is a natural setting for regeneration initiatives.[24] This is reflected in the settlements, which have vast areas of secondary forest (Figure 7). In 2019, approximately 2.1 million hectares had been naturally regenerated, occupying almost 25% of the entire deforested area in the Amazon settlements.[25] Figure 7 also shows that all settlements have a significant fraction of their deforested area occupied by secondary vegetation. This indicates that even in the settlements where there is the most deforestation, there is room for forest restoration initiatives.

Figure 7. Secondary Vegetation in Settled Areas in the Amazon Biome, 2012-2019

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from Acervo Fundiário/INCRA, Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos/INCRA, Biomas do Brasil/IBGE (2019), and Mapbiomas (2022),[26] 2023

Even without public incentives, almost a quarter of the deforested area in the settlements is already in the process of regeneration. This share could grow rapidly with a program that pays settlers to promote forest restoration and management. These results indicate that environmental restoration policies can be a promising strategy for the region.

Conclusion

The urgency of protecting the Amazon and achieving zero deforestation in the region by 2030 demands that efforts be directed towards high-impact actions with rapid effects. This is why altering land use patterns in the region’s settled areas is a national priority.

Deforestation in the settlements is concentrated in a small group of settlements, indicating that targeted actions are likely to be effective. Policies that prioritize these areas could therefore bring significant results for the preservation of the forest as a whole.

Yet curbing deforestation in settled areas is not enough to guarantee the success of Brazil’s land access policy. It is essential that rural settlers have the means to develop productive and sustainable economic activities. This requires the implementation of comprehensive policies that promote environmental conservation and encourage economic activities that are compatible with the forest.

The authors would like to thank the methodological support of Juliano Assunção. This publication benefited from the comments and suggestions of Luciano Mattos (MDA), Cristina Leme Lopes, and João Arbache. We would also like to thank Natalie Hoover El Rashidy, Giovanna de Miranda, and Camila Calado for the editing and revision of the text and Nina Oswald Vieira for formatting and graphic design.

[1] Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra. Prodes Amazônia. 2023. Access date: May 24, 2023. bit.ly/3qFHtzl.

[2] In the fifth edition of the Action Plan to Prevent and Combat Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (Plano de Prevenção e Combate ao Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal – PPCDAM), zero deforestation by 2030 was defined as ending illegal deforestation and compensating for legal deforestation. bit.ly/3DxGnsc.

[3] Gandour, Clarissa and João Mourão. Coordenação Estratégica para o Combate ao Desmatamento na Amazônia: Prioridades para os Governos Federal e Estaduais. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022. bit.ly/CoordenacaoEstrategica.

[4] Chiavari, Joana, Cristina L. Lopes, and Julia N. de Araujo. Panorama dos Direitos de Propriedade no Brasil Rural. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2021. bit.ly/PanoramaDireitosDePropriedade.

[5] Souza, Maria Lucimar. Assentamentos Rurais da Amazônia Diretrizes para a Sustentabilidade. Amazônia 2030, 2022. bit.ly/3Y8fe8M.

[6] Souza, Maria Lucimar. Assentamentos Rurais da Amazônia Diretrizes para a Sustentabilidade. Amazônia 2030, 2022. bit.ly/3Y8fe8M.

[7] Chiavari, Joana, Cristina L. Lopes e Julia N. de Araujo. Panorama dos Direitos de Propriedade no Brasil Rural. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2021. bit.ly/PanoramaDireitosDePropriedade.

[8] Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (INCRA). Acervo Fundiário. Assentamentos Brasil. Access date: April 28, 2023. bit.ly/44ytbyD.

[9] Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (INCRA). Assentamentos – Relação de Projetos. Access date: April 28, 2023. bit.ly/3EjGUyv.

[10] Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra (OBT), and Projeto de Monitoramento do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal por Satélite (PRODES). Downloads. Access date: May 24, 2023. bit.ly/3L7iH27.

[11] Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Biomas do Brasil: shapefile, 2019. 2019. Access date: September 16, 2020. bit.ly/4690QQH.

[12] These figures do not include settlements of the following types: RESEX, RDS, FLONA and FLOE. These types of settlements correspond to sustainable use conservation units recognized by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) as part of the National Agrarian Reform Program (PRNA) and thus have access to public policies associated with programs aimed at beneficiaries of agrarian reform. If they had been included, settlements would occupy 14% of the biome’s area and would account for 30% of deforestation after 2012.

[13] Departamento Nacional da Infraestrutura de Transportes (DNIT) and Sistema Nacional de Viação (SNV). Plano Nacional de Viação e Sistema Nacional de Viação. 2018. Access date: February 22, 2019. bit.ly/3YZH9bj.

[14] Veríssimo, et al. As 5 Amazônias: bases para o desenvolvimento sustentável da Amazônia Legal. Amazônia 2030, 2022. bit.ly/3qFHtzl.

[15] Azevedo, Tasso et al. Relatório Anual do Desmatamento no Brasil. Mapbiomas, 2023. bit.ly/3rKKzlY.

[16] Gandour, Clarissa and Juliano Assunção. O Brasil Sabe Como Deter o Desmatamento na Amazônia: Monitoramento e Fiscalização Funcionam e Devem ser Fortalecidos. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2019. bit.ly/3Khr36O.

[17] Gandour, Clarissa. Políticas Públicas para Proteção da Floresta Amazônica: O que Funciona e Como Melhorar. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2021. bit.ly/PolíticasProteçãoAMZ.

[18] Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Renováveis (IBAMA). Fiscalização – auto de infração. 2023. Access date: October 21, 2023. bit.ly/3qTy5IA.

[19] Souza, Maria Lucimar and Ane Alencar. Assentamentos Sustentáveis na Amazônia. IPAM, 2021. bit.ly/3OcOWxK.

[20] The project was led by the IPAM Institute.

[21] As part of the project, (i) around 2,700 families received information on the country’s environmental and land regulations, (ii) 1,300 received administrative support to register with the Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural – CAR), (iii) 650 received technical assistance to develop forest-compatible activities (intensification of livestock farming, agroforestry systems, and horticulture), and (iv) 350 had access to payments for environmental services amounting to as much as R$ 1,680 per year. The amount received was conditional on compliance with requirements such as preserving vegetation cover and refraining from using fire as a management technique.

[22] Souza, Maria Lucimar. Assentamentos Rurais da Amazônia: Diretrizes para a Sustentabilidade. Amazônia 2030, 2022. bit.ly/3Y8fe8M.

[23] Demarchi et al. Beyond Reducing Deforestation: Impacts of REDD+ project on Household Livelihoods. Center for Environmental Economics – Montpellier (CEE – M). Working paper, 2022. bit.ly/47KDAK4.

[24] Assunção, Juliano, Cláudio Almeida, and Clarissa Gandour. O Brasil Precisa Monitorar sua Regeneração Tropical: Sistema de Monitoramento é Tecnologicamente Factível, mas Precisa de Apoio da Política Pública. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2020. bit.ly/RegeneracaoTropical.

[25] The secondary vegetation data was generated by MapBiomas. When compared to the loss of primary vegetation from the “Deforestation History 1987-2019” collection, approximately 2.1 million hectares of secondary vegetation account for 24.4% of the loss of primary vegetation in the settlements. If we consider the deforested area until the PRODES year 2019 according to the PRODES/INPE data, the same 2.1 million hectares correspond to 16% of the deforested area in the settlements.

[26] MAPBIOMAS. Histórico do Desmatamento 1987 – 2019 – Coleção 6.0. Access date: June 6, 2023. brasil.mapbiomas.org.