Introduction

The bioeconomy sector has emerged as a new production paradigm gaining significant attention in Brazil and globally, and is the focus of a forward-looking G20 initiative introduced by the third Lula administration.[1]

An evolution has been underway in Brazil for several years to begin to better regulate the bioeconomy and to provide a broad legal framework, but major progress has been made since President Lula da Silva took office again in 2023.

The first significant action taken by the new Lula government in this arena was the creation of a vice-ministry level office, the National Secretariat of Bioeconomy (Secretaria Nacional de Bioeconomia – SNB), within Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima – MMA). The Secretariat’s mission is to prioritize efforts to enable economic growth while conserving biodiversity and promoting social justice.

The federal government has also established a National Bioeconomy Strategy to coordinate and implement public policies aimed at developing the bioeconomy and integrating economic and social practices with the protection of biodiversity, food, climate and energy security. The publication of a specific strategy for the bioeconomy demonstrates the current government’s commitment to this new production model.[2]

Researchers from the Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-RIO) have mapped and analyzed Brazil’s regulatory frameworks and governance structure related to the bioeconomy, with a focus on the post-2023 period. The researchers use the report “Bioeconomy in the Amazon: Conceptual, Regulatory and Institutional Analysis,” published by CPI/PUC-RIO in September 2022, as a starting point to understand what has changed with the new Lula government, what regulatory progress has been made, how the new ministerial office has advanced its agenda and how the National Bioeconomy Strategy addresses and integrates different visions of the bioeconomy.[3]

This publication provides a current and comprehensive overview of the bioeconomy in Brazil; this is especially relevant at a time of political and strategic transformation ahead of the development of the National Bioeconomy Development Plan (Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Bioeconomia – PNDBIO). The PNDBIO will be the main instrument for implementing the National Bioeconomy Strategy. It represents an important opportunity to comprehensively carry out the Strategy by ensuring effective coordination between government agencies. This will allow the bioeconomy to become a key development pathway that will promote the sustainable use of biodiversity, incorporate Indigenous and other traditional knowledge and perspectives, develops new industry models, accelerate the clean energy transition and create wealth while also striving for socio-economic inclusion.

Bioeconomy Visions

The forward-looking report “Bioeconomy in the Amazon: Conceptual, Regulatory and Institutional Analysis”[4] proposed the classification of bioeconomy into three visions, biotechnological, bioresources and bioecological,[5] with the aim of organizing multiple narratives, strategies, governance structures and regulatory frameworks. At that point in time, Brazil had no regulatory frameworks that fully defined the bioeconomy.

The three visions all depend on the use of biobased raw materials to produce goods and services, although each seeks to serve a different purpose. The biotechnological vision focuses on the innovation and commercialization of products derived from biotechnology; the bioresources vision promotes the production and processing of biomass to replace fossil-fuel based raw materials; and the bioecological vision aims to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity.[6]

This nomenclature—biotechnology, bioresources and bioecology—has not been universally adopted in the literature, but it is common for the bioeconomy to be classified on the basis of these three elements: technology, biomass and biodiversity.[7],[8] These visions of the bioeconomy are used in this publication to assess the changes brought about by the new Lula government, both at the regulatory and institutional levels.

Key Messages

- The bioeconomy has gained prominence in the new Lula government with the creation of the National Secretariat of Bioeconomy and the publication of the National Bioeconomy Strategy. This new regulatory framework is fundamental to giving the country direction in this area, coordinating and aligning the various policies, plans and programs that deal with different sectors of the bioeconomy.

- The National Bioeconomy Strategy is primarily aligned with the bioecological vision, as it defines bioeconomy restrictively as a model of economic and productive development based on the sustainable use, regeneration and conservation of biodiversity.

- The development and espousal of the National Bioeconomy Development Plan (Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Bioeconomia – PNDBIO) is an opportunity to broaden the concept proposed by the National Strategy and to ensure effective coordination across the different visions of the bioeconomy with the public policies in place.

- In addition to the National Strategy, other regulatory frameworks and programs relevant to the bioeconomy have been enacted by the new administration, in particular the Fuel of the Future Law, the Productive Forests National Program and the National Food Supply Policy (Política Nacional de Abastecimento Alimentar – PNAAB), which address biofuels, the use and conservation of biodiversity, and food security.

- New ministries have taken a leading role. The MMA now leads the agenda at the federal level, together with the Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services (Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria, Comércio e Serviços – MDIC) and the Ministry of Finance (Ministério da Fazenda – MF). However, the PNDBIO is an opportunity for improved coordination across all ministries.

Regulatory Advances

The Bioeconomy Gets a National Strategy

On June 5, 2024, the federal government issued Decree no. 12,044 establishing the National Bioeconomy Strategy with the aim of coordinating and implementing public policies to develop the bioeconomy, in conjunction with civil society and the private sector.[9]

The decree establishes the guidelines and objectives of the National Strategy and provides for the creation of the National Bioeconomy Commission, which will be responsible for creating and implementing the PNDBIO. The decree also provides for the creation, by the MMA, of a National Information and Knowledge System on the Bioeconomy.

For the purposes of the National Strategy, bioeconomy is “the model of productive and economic development based on values of justice, ethics and inclusion, capable of generating products, processes and services efficiently, based on the sustainable use, regeneration and conservation of biodiversity, guided by scientific and traditional knowledge and its innovations and technologies, with an eye toward adding value, generating work and income, sustainability and climate balance.” (as translated by the authors).[10]

While comprehensive, this definition of the bioeconomy is based primarily on the bioecological vision, as it describes a productive model “based on the sustainable use, regeneration and conservation of biodiversity.”[11] The Strategy does not use the term biological resources, which is employed by the European Union and other countries such as Colombia, Costa Rica and Canada and appears to not include products and processes derived from biomass, such as sugar cane, soy and planted forests.[12],[13],[14],[15]

As a whole, though, the National Strategy integrates all three visions of the bioeconomy. Through this framework, the bioeconomy emerges as a new paradigm for economic development. The Strategy mandates that the production model be guided by innovation and scientific and traditional knowledge in order to add value to products, processes and services derived from the sustainable use of biodiversity. In this sense, the National Strategy also incorporates the biotechnological vision into its concept of the bioeconomy, albeit less overtly than the bioecological vision. Its guidelines seek to expand research, development and innovation (RD&I) related to biodiversity assets, as well as reinforce the importance of fair and equitable sharing of the benefits derived from this use. This strengthens the obligations set out in the Biodiversity Legal Framework which regulate and protect access to genetic heritage and associated Indigenous and other traditional knowledge.[16]

The National Strategy adopts the core objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity and addresses additional emerging issues, such as social justice and equity, by targeting the reduction of inequalities and the inclusion of women and young people in the bioeconomy. The Strategy also promotes the restoration of native vegetation, healthy food systems capable of promoting food security and sociobiodiversity (in order to guarantee the conservation and regeneration of biodiversity) and ecosystem services.

The bioresources vision is not explicitly included in the National Strategy, although there is a guideline that addresses the decarbonization of production processes and biomass processing, as long as it does not lead to the conversion of original native vegetation. The bioresources vision is also considered indirectly in the objective to strengthen national bio-based production in the transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient economy. The National Bioeconomy Strategy does not focus on the climate change challenge; it places its emphasis on biodiversity and food security issues. The bioeconomy and climate agendas could be much better aligned.

Although the concept of bioeconomy established by the National Strategy is quite limited in what it directly addresses, the guidelines and objectives are broad enough to allow for comprehensive implementation. All three classifications, biotechnological, bioresources and bioecological, can be included in the PNDBIO, which is in the process of being drafted and already has the support of several ministries. According to the National Strategy, the Plan will be guided by at least five thematic axes and should be framed in line with public policies on environmental protection, industrial development, science, technology and innovation, agriculture, family farming and food security, biodiversity and access to genetic heritage and benefit sharing and climate change, among others.[17]

It is important to point out that the National Strategy was adopted at a time when the country already had an extensive regulatory framework covering all visions of the bioeconomy. The new government has adopted additional regulatory frameworks that reinforce the importance of different sectors (Figure 1). Although the Strategy needs to be implemented in coordination with other public policies already in force, it is important that its objectives also guide the evolution of the agenda in the country.

New Regulatory Frameworks Reinforce the Potential of the Bioeconomy in Brazil

Regulatory Frameworks and the Different Visions of the Bioeconomy

In addition to the adoption of the National Bioeconomy Strategy in 2024, several key regulatory frameworks covering the different visions of the bioeconomy have been adopted since 2023. The recently adopted frameworks primarily address food security, the use and conservation of biodiversity and the promotion of biofuels.

In the Aquaculture, Fisheries and Mangroves sector, the National Program for Sustainable Aquaculture Development (Programa Nacional de Desenvolvimento Sustentável da Aquicultura – PROAQUI) and the National Program for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Mangroves (Programa Nacional para a Conservação e Uso Sustentável dos Manguezais – PROMANGUEZAL) were adopted.[18],[19] These programs provide important measures to combat food insecurity and biodiversity loss. PROAQUI seeks to strengthen and develop aquaculture production chains that foster the bioeconomy. PROMANGUEZAL focuses on the conservation, recovery and sustainable use of mangrove resources and their ecosystem services; it also promotes the use of native species to generate income for traditional communities, with the proper sharing of any resulting benefits. This is in line with the guidelines and objectives of the National Bioeconomy Strategy and the Biodiversity Legal Framework.

The Productive Forests National Program (Programa Nacional de Florestas Produtivas) should also be highlighted in the sector of Sociobiodiversity Products.[20] It seeks to recover and reforest altered or degraded areas for productive purposes in rural establishments owned by family farmers, including agrarian reform settlements and Indigenous and traditional peoples territories and communities. The program, which spans the six Brazilian biomes, promotes food security and biodiversity conservation with a concentration on healthy food output and sociobiodiversity products, such as açaí, that come from local cultures and communities.

In the Family Agriculture and Organic Farming sector, the National Program of Urban and PeriUrban Agriculture has been adopted.[21] This is an innovative Brazilian government effort to promote the sustainable use of agro-sociobiodiversity to produce healthy food. The National Food Supply Policy (Política Nacional de Abastecimento Alimentar – PNAAB), part of the National Food and Nutritional Security System (Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional – SISAN), also aims to promote sustainable and healthy food systems, based on agroecology and sociobiodiversity.[22] These policies all reflect a commitment to food security along with the protection of biodiversity, with a goal of increasing productivity and adding value.

In the biofuels sector, the Fuel of the Future Law was passed, which aims to decarbonize road, air transport and natural gas, update the percentages of ethanol blended into gasoline and biodiesel blended into diesel, and encourage the use of green diesel and sustainable fuel.[23] This framework is particularly important in the bioresources vision of the bioeconomy to combat climate change by replacing fossil fuels with biobased fuels, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Figure 1 illustrates the most important regulatory frameworks for the bioeconomy in Brazil and classifies them according to the three visions: biotechnological, bioresources and bioecological.

The biotechnological vision emphasizes the use of research and commercial application of biotechnology in different sectors of the economy. Legal frameworks addressing science, research, technology and innovation are essential to this vision. The bioresources vision encourages the development of new processing chains for biobased raw materials with the aim of replacing fossil raw materials. Policies and regulations that promote the production and processing of biomass for biofuels, biorefineries and energy generation are highlighted, as well as legal frameworks for land use. Finally, the bioecological vision emphasizes the importance of the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and environmental services. Family, organic, and low-carbon crops as well as the knowledge and production methods of traditional peoples and communities are valued. Policies and regulations valuing Brazilian sociobiodiversity, protection, and sustainable use of forests and other forms of native vegetation are central to this vision.

It is important to note that the visions are all somewhat porous and that a given regulation may be relevant to more than one vision. The classification presented considers the alignment between the legislative aims and the visions of the bioeconomy.

Figure 1. Regulatory Frameworks and the Three Visions of the Bioeconomy

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO, 2024

Regulatory Frameworks and Structuring Public Policies for the Bioeconomy

In addition to the policies that are directly linked to the different visions of the bioeconomy, there are others that are enabling and structuring for the bioeconomy itself, such as land regularization, the circular economy, and the ecological transformation of the economy.

The federal government has reinstituted the Technical Office for the Distribution and Land Regularization of Federal Rural Public Lands, with a particular focus on the creation of new protected areas, the demarcation of indigenous lands and the regularization of family farmers.[24] So far, the new Lula administration has ratified ten additional indigenous territories and officially defined the boundaries of four.[25] The government has instituted the National Policy for Quilombola Territorial and Environmental Management (Política Nacional de Gestão Territorial e Ambiental Quilombola – PNGTAQ) and, with the new regulation of the Public Forest Management Law, it has allowed the recognition of traditional territories in undesignated public areas, through the Concession of Real Right of Use.[26],[27] To strengthen the national agrarian reform program, the government created the Terra da Gente Program with the aim of promoting access to land, productive inclusion to reduce social inequality, and increased food production.[28] Finally, in 2023, a working group was set up to develop a National Land Governance Policy and a National Land Regularization Plan, but these have not yet been implemented.[29]

The new National Impact Economy Strategy (Estratégia Nacional de Economia de Impacto – ENIMPACTO) is also important for the success of the bioeconomy, as it promotes initiatives that enable the restoration of natural resources and contribute to an inclusive, equitable and regenerative economic system.[30] This aligns with the objectives of the National Bioeconomy Strategy and serves as an instrument to promote the different bioeconomy sectors. The National Circular Economy Strategy (Estratégia Nacional de Economia Circular – ENEC) also impacts the bioeconomy, as it focuses on the conscious use and reuse of natural resources, seeking to guarantee more fair, inclusive and equitable transition.[31]

In December 2023, the Ministry of Finance launched the Ecological Transformation Plan, which has several areas of focus, including bioeconomy and agri-food systems, important vehicles for biodiversity conservation and food security, as well as energy transition with an emphasis on biofuels.[32]

Finally, in August 2024, the three branches of the Brazilian federal government signed a Pact for Ecological Transformation, in which they commit to acting, within their respective areas of responsibility and power, to promote a sustainable economic development based on social, climate and environmental justice that is capable of safeguarding the rights of present and future generations.[33] Through this pact, the legislative, executive and judicial branches are committed to prioritizing regulations that reduce environmental impact and stimulate new economies of nature, including the bioeconomy. In addition, the pact adopts three priority axes with policy instruments to accelerate territorial and land-use planning, the process of a just energy transition including expanding the use of biofuels, and sustainable development with an emphasis on economic activities compatible with the conservation of biodiversity and the Brazilian biomes.

Institutional Advances

The Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change Takes the Lead

The MMA played a secondary role in the governance of the country’s bioeconomy until 2023, when it took center stage in the agenda with the creation of the National Secretariat of Bioeconomy (SNB). Among its duties, the SNB is responsible for coordinating the National Bioeconomy Strategy and the PNDBIO. Given the multidisciplinary and cross-cutting nature of the bioeconomy, the National Strategy is being coordinated jointly by the MMA with the Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services (MDIC) and the Ministry of Finance (MF). In addition, the MMA is leading the drafting of the PNDBIO with the MDIC and MF, in partnership with other ministries.[34] This cross-cutting approach is not limited to government bodies. The MMA has promoted technical and scientific seminars with representatives from the government, civil society, academia and the private sector to draw up the plan.[35]

The SNB office has three divisions: the Department of Policies to Foster Bioeconomy, responsible for drawing up and implementing bioeconomy policies and strategies in the broadest sense; the Department of Shared Fisheries Resources Management, which will carry out its work in conjunction with the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Ministério da Pesca e Aquicultura – MPA); and the Department of Genetic Heritage, responsible for implementing the instruments of the Biodiversity Legal Framework. The Department of Genetic Heritage is responsible for implementing the National Program for Benefit Sharing (Programa Nacional de Repartição de Benefícios – PNRB), for operating the National System for Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge Management (Sistema Nacional de Gestão de Patrimônio Genético e do Conhecimento Tradicional Associado – SISGEN) and is also the Executive Secretariat of the Genetic Heritage Management Council (Conselho de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético – CGEN).

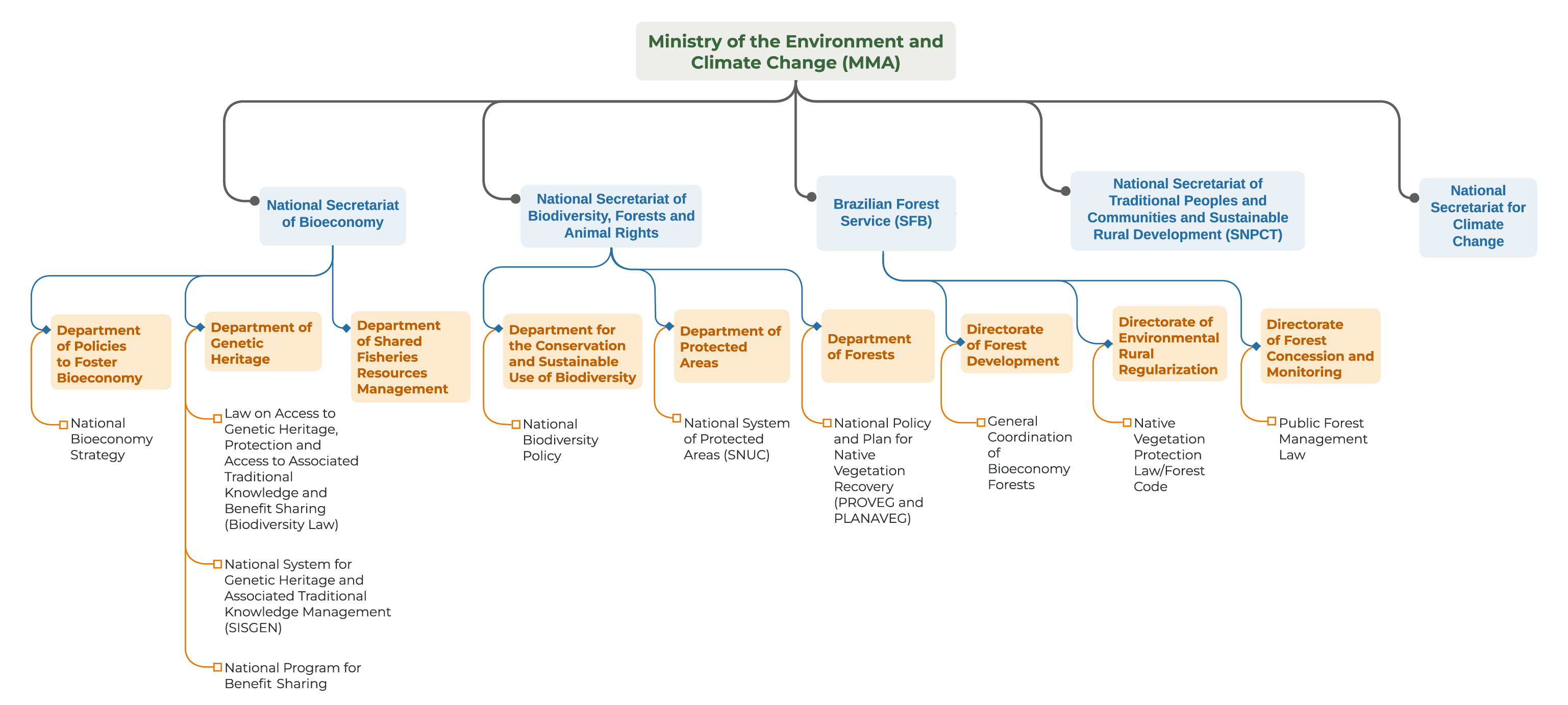

In addition to the SNB, the MMA also has other key posts that are relevant to the success of the bioeconomy, such as the National Secretariat of Biodiversity, Forests and Animal Rights; the National Secretariat of Traditional Peoples and Communities and Sustainable Rural Development (Secretaria Nacional de Povos e Comunidades Tradicionais e Desenvolvimento Rural Sustentável – SNPCT); and the Brazilian Forest Service (Sistema Florestal Brasileiro – SFB). These offices are responsible for policies and programs related to sociobiodiversity, agrobiodiversity, agroextractivism, agroforestry, sustainable forest management, forest restoration, forest bioeconomy and other actions for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity (Figure 2).

Although there are important synergies between the bioeconomy and climate change agendas, among the responsibilities of the National Secretariat for Climate Change and the National Secretariat of Bioeconomy there is no specific mention of policies and programs that handle the energy transition and decarbonization of the economy by replacing fossil raw materials with biomass. In addition, the National Secretariat for Climate Change does not appear as a relevant and active role alongside the National Secretariat for Biodiversity. There is a focus on the bioecological vision in the MMA’s work on the bioeconomy agenda, with some relevance of the biotechnological vision when related to research, development and innovation to add value to products and services from sociobiodiversity. However, it is possible to more fully integrate all visions in the PNDBIO.

Figure 2. Institutional Mapping of the Bioeconomy in the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO, 2024

The Bioeconomy across Ministries

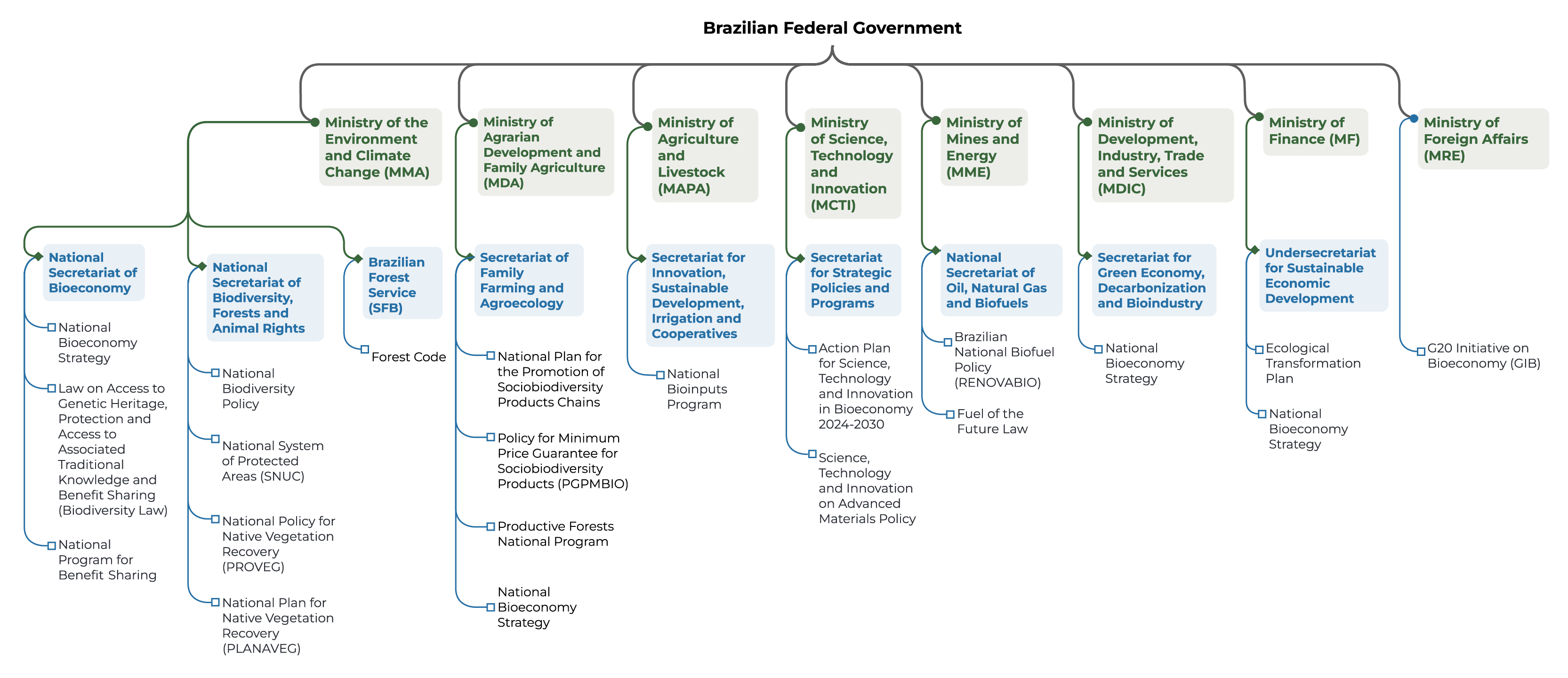

Under the Bolsonaro administration, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação – MCTI) took the lead in building a national agenda for the bioeconomy. In the current Lula administration, although the MMA has taken on a more important role, the agenda is managed cooperatively by several ministries of the Brazilian Federal Government, due to its multisectoral nature and the extensive legal framework related to it, which is implemented through multiple ministries (Figure 3). The work of these ministries, through public policies, plans, programs and projects, takes place in a broader spectrum of the bioeconomy, involving sectors related to the bioecological, biotechnological, and bioresources visions.

The Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Agriculture

The Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Agriculture (Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário e Agricultura Familiar – MDA) was reinstituted in 2023 and the office of the Secretary for Family Farming and Cooperativism, which previously belonged to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (Ministério da Agricultura e Pecuária – MAPA) has been replaced with the Secretariat of Family Farming and Agroecology (Secretaria de Agricultura Familiar e Agroecologia – SAFA). SAFA runs some important programs for the bioeconomy, such as the Bioeconomy Brazil – Sociobiodiversity Program, the Social Biofuel Seal Program and the National Program for Strengthening Family Farming (Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar – PRONAF). PRONAF has a specific sub-program for the bioeconomy, called PRONAF Bioeconomia, which finances family farmers in activities related to forestry, land recovery and advances in the productive capacity of soil. Recently, the MDA launched the Productive Forests National Program, with the aim of promoting processes to restore degraded areas in settlements and while contributing to sustainable production and food security.

The National Supply Company (Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento – CONAB), previously an entity linked to MAPA, has been transferred to the MDA, bringing with it the Policy for Minimum Price Guarantee for Sociobiodiversity Products (Política de Garantia de Preços Mínimos para os Produtos da Sociobiodiversidade – PGPMBIO) which guarantees a minimum price for extractive products derived from the sustainable exploration of biodiversity thereby helping to conserve Brazilian biomes.[36]

Figure 3. Institutional Mapping of the Bioeconomy in Brazil

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO, 2024

The Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock

Crops are central to the bioeconomy in its broadest definition, as suppliers of bio-based raw materials for the production of goods and services. In this context, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAPA) plays an important role in overseeing agricultural policies for the production of biomass and bio-inputs. The Secretariat for Innovation, Sustainable Development, Irrigation and Cooperatives is MAPA’s central office for handling this work, and is responsible for the National Bioinputs Program and for implementing the National Plan for the Development of Planted Forests (Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento de Florestas Plantadas – PNDF). The planted forest sector is important for the production of cellulose, a natural polymer derived from plants that can be used as a substitute for plastic (which is derived from petroleum), helping to reduce the use of and dependence on fossil fuels.

MAPA, together with the MMA and the MDA, is also responsible for implementing the National Policy for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Genetic Resources for Food, Agriculture and Livestock. MAPA runs the National Program for the ex situ Conservation of Genetic Resources, the MMA runs the National Program for the in situ Conservation of Genetic Resources and the MDA runs the National Program for the on farm Conservation of Genetic Resources.[37],[38],[39] There is now unprecedented joint coordination of the bioeconomy that has been established explicitly among the governing bodies.

Finally, it is important to highlight the role of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária – EMBRAPA), an entity linked to MAPA, in developing research and technologies related to the bioeconomy, such as EMBRAPA Agroenergy, which develops solutions for converting biomass into biofuels and bioproducts, such as the project aimed at using macauba to produce aviation fuel, green diesel, thermal energy and other value-added bioproducts.[40]

The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation

The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) plays an important role in the development of the bioeconomy, despite not having been selected by the current government to be part of the coordination of the National Bioeconomy Strategy. Its organizational structure includes a Coordination of Programs and Projects for Bioeconomy, linked to the Department of Thematic Programs of the Secretariat for Strategic Policies and Programs. The Secretariat for Strategic Policies and Programs also works on the development of the Action Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation in Bioeconomy 2024-2030 (Plano de Ação em Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação em Bioeconomia 2024-2030 – PACTI-Bioeconomy) and the National Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation (Estratégia Nacional de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação – ENCTI), which has a focus on ecological transition, biodiversity and the bioeconomy. The Secretariat for Technological Development and Innovation coordinates the Bioeconomy Production Chains Program, which until May 2024 supported 54 research and development projects that encourage production chains for products from Brazilian biodiversity, with an investment of approximately R$ 130 million.[41] In addition, the Center for Strategic Studies and Management (Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos – CGEE), a social organization linked to the MCTI, carries out various studies and projects related to various sectors of the bioeconomy.

The MCTI coordinates the National Technical Commission on Biosafety (Comissão Técnica Nacional de Biossegurança – CTNBIO), which is responsible for providing technical support for the implementation of the National Biosafety Policy. Finally, other entities linked to the MCTI also play an important role in RD&I in the bioeconomy and related themes, such as the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia – INPA), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq) and the Brazilian Company of Research and Industrial Innovation (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa e Inovação Industrial – EMBRAPII).

The Ministry of Mines and Energy

The Ministry of Mines and Energy (Ministério de Minas e Energia – MME) has a long-standing role in the Brazilian biofuels program, which is becoming increasingly important in Brazil. The ministry is responsible for coordinating the Brazilian National Biofuel Policy (Política Nacional de Biocombustível – RENOVABIO), through the National Secretariat of Oil, Natural Gas and Biofuels (Secretaria Nacional de Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis – SNPGB) and the Brazilian National Agency for Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis – ANP), an entity linked to the MME. The ANP is the body responsible for authorizing biofuel production and operating the Decarbonization Credits (Créditos de Descarbonização – CBIOs) management platform. The SNPGB coordinates the RENOVABIO Committee and the Biofuels Department is responsible for conducting biofuel development programs. In addition, the MME holds the presidency of the National Energy Policy Council (Conselho Nacional de Política Energética – CNPE), the body responsible for the recently published Fuel of the Future Law that includes measures, initiatives, and programs to promote low-carbon mobility.

The Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services

The Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services (MDIC) has become more prominent in the current Lula administration. Along with being one of the ministries responsible for jointly coordinating the National Bioeconomy Strategy, the Secretariat for Green Economy, Decarbonization and Bioindustry has divisions relevant to activities involving the bioeconomy. The Department of New Economies is responsible for implementing the National Bioeconomy Strategy and the National Circular Economy Strategy (Estratégia Nacional de Economia Circular – ENEC). The Department of Genetic Heritage and Productive Chains of the Biomes and the Amazon coordinates the Program of Routes of Productive Chains of Sociobiodiversity and the Department of Bioindustry and Strategic Health Supplies is responsible for the Amazon Seal Program.

With the restructuring of the Ministry of Finance, the MDIC took over the governance of issues related to intellectual property rights and became responsible for the Brazil’s National Intellectual Property Strategy. In addition, the National Institute of Industrial Property (Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial – INPI), an entity linked to the ministry, is responsible for ensuring that patent applications on access to Brazilian genetic heritage and/or associated traditional knowledge comply with the Biodiversity Law.[42] The National Council for Industrial Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Industrial – CNDI), another entity linked to the MDIC, is responsible for executing the Action Plan for Neoindustrialization 2024-2026, which has a specific mission focused on “bioeconomy, decarbonization and energy transition and security to guarantee resources for future generations.”[43]

The Ministry of Finance

The Ministry of Finance (MF) plays an important role in designing and structuring the bioeconomy in Brazil and helps coordinate the National Bioeconomy Strategy with the MMA and MDIC. The Secretariat of Economic Policy, through the Undersecretariat for Sustainable Economic Development, coordinates and implements the Ecological Transformation Plan, which has a pillar dedicated to the Bioeconomy and Agri-Food Systems.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ministério das Relações Exteriores – MRE) began to play a prominent and coordinating role in the current administration on the subject of the bioeconomy with the creation of the G20 Initiative on Bioeconomy (GIB), under the Brazilian presidency of the G20, in 2024. Through this Initiative, the MRE worked together with the MMA, MDIC, MCTI and MF, and was able to count on the participation of several other ministries to put the bioeconomy issue in the spotlight at the multilateral level. As a result of this initiative, the National Bioeconomy Strategy has gained greater traction, with discussions and collaborations between various ministries to draw up the PNDBIO.

Other Relevant Ministries

Other ministries have bodies or responsibilities related to the bioeconomy in their governance structure. The Ministry of Integration and Regional Development (Ministério da Integração e do Desenvolvimento Regional – MIDR) launched the National Bioeconomy and Sustainable Regional Development Strategy (Estratégia Nacional de Bioeconomia e Desenvolvimento Regional Sustentável – BIOREGIO) with the aim of developing the bioeconomy by strengthening production chains and the sustainable management of natural resources in different regions of Brazil. The National Aquaculture Secretariat of the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Ministério da Pesca e Aquicultura – MPA) is responsible for implementing the National Program for Sustainable Aquaculture Development. The creation of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples (Ministério dos Povos Indígenas – MPI) demonstrates the importance that the current administration gives to the country’s Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples are central players in a bioeconomy agenda in Brazil and, although the National Strategy emphasizes traditional knowledge, a role for the MPI has not yet been defined. Finally, education, science and research are critical to the success of the bioeconomy and, for this reason, the Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação – MEC) is particularly important because of its relationships with Brazil’s public universities and research institutes.

This report received financial support from the Institute Climate and Society (ICS) and Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI).

The authors would like to thank Sarah Robbins, Natalie Hoover El Rashidy, Giovanna de Miranda, and Camila Calado for proofreading and editing the text, and Meyrele Nascimento, Nina Oswald Vieira, and Julia Berry for formatting and graphic design.

[1] The Lula administration proposed the Bioeconomy Initiative in 2024, bringing the topic of the bioeconomy to the G20 for the first time. Learn more at: G20 Brasil 2024. Initiative on Bioeconomy. 2024. Access date: October 17, 2024. bit.ly/3YtvySa.

[2] Decree no. 12,044, June 5, 2024. bit.ly/4g65CnF.

[3] Lopes, Cristina L. and Joana Chiavari. Bioeconomy in the Amazon: Conceptual, Regulatory and Institutional Analysis. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022. bit.ly/BioeconomyAmazon.

[4] Lopes, Cristina L. and Joana Chiavari. Bioeconomy in the Amazon: Conceptual, Regulatory and Institutional Analysis. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022. bit.ly/BioeconomyAmazon.

[5] Bugge, Markus M., Teis Hansen and Antje Klitkou. “What is the bioeconomy? A review of the literature”. Sustainability 8, no. 7 (2016). bit.ly/3B0NOI9.

[6] Lopes, Cristina L. and Joana Chiavari. Bioeconomy in the Amazon: Conceptual, Regulatory and Institutional Analysis. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022. bit.ly/BioeconomyAmazon.

[7] Lesenfants, Yves et al. Re-imagining bioeconomy for Amazonia. Inter-American Development Bank and Igarapé Institute, 2024. bit.ly/4eJlGKR.

[8] Dias, George P. et al. Uma Base de Conhecimento para a Estratégia Nacional de Bioeconomias. São Paulo: Instituto de Engenharia, 2024. bit.ly/3U6qpOn.

[9] Decree no. 12,044, June 5, 2024. bit.ly/4g65CnF.

[10] Original text: “o modelo de desenvolvimento produtivo e econômico baseado em valores de justiça, ética e inclusão, capaz de gerar produtos, processos e serviços, de forma eficiente, com base no uso sustentável, na regeneração e na conservação da biodiversidade, norteado pelos conhecimentos científicos e tradicionais e pelas suas inovações e tecnologias, com vistas à agregação de valor, à geração de trabalho e renda, à sustentabilidade e ao equilíbrio climático”. Learn more at: Decree no. 12,044, June 5, 2024. bit.ly/4g65CnF.

[11] Ibid.

[12] European Commission. A sustainable bioeconomy for Europe: strengthening the connection between economy, society and the environment – Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. 2018. bit.ly/4h55THT.

[13] Gobierno de Colombia. Bioeconomia para una Colombia Potencia viva y diversa: Hacia una sociedad impulsada por el Conocimiento. 2020. bit.ly/3BNVJLK.

[14] Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Telecomunicaciones. Estrategia Nacional de Bioeconomía Costa Rica 2020-2030. 2020. bit.ly/3UARABx.

[15] Bioindustrial Innovation Canada et al. Canada’s Bioeconomy Strategy: Leveraging our Strengths for a Sustainable Future. 2019. bit.ly/407djEs.

[16] Law no. 13,123, May 20, 2015. bit.ly/406fgBf.

[17] The thematic axes are: I – public and private financial instruments; II – normative, regulatory and fiscal instruments; III – data, information and knowledge; IV – infrastructure, sustainable production systems, markets and value chains; and V – professional education, research, science, technology and innovation.

[18] Decree no. 11,852, December 26, 2023. bit.ly/40aKRld.

[19] Decree no. 12,045, June 5, 2024. bit.ly/4eKAkBC.

[20] Decree no. 12,087, July 3, 2024. bit.ly/48eiIfd.

[21] Decree no. 11,700, September 12, 2023. bit.ly/3UDGZWa.

[22] Decree no. 11,820, December 12, 2023. bit.ly/40c8Jou.

[23] Law no. 14,993, October 8, 2024. bit.ly/4eKMeLV.

[24] Decree no. 11,688, September 5, 2023. bit.ly/4hp8mgL.

[25] Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Situação Jurídica das TIs no Brasil hoje – Demarcações nos últimos governos. 2024. Access date: October 16, 2024. bit.ly/487gqhR.

[26] Decree no. 11,786, November 20, 2023. bit.ly/48l3oqB.

[27] Decree no. 12,046, June 5, 2024. bit.ly/3Y9qv9u.

[28] Decree no. 11,995, April 15, 2024. bit.ly/3Yuru5x.

[29] MDA Ordinance no. 17, June 21, 2023. bit.ly/40sP0RR.

[30] Decree no. 11,646, August 16, 2023. bit.ly/3YEca6t.

[31] Decree no. 12,082, June 27, 2024. bit.ly/4hdQAwS.

[32] MF. Plano de Transformação Ecológica. 2024. Access date: October 9, 2024. bit.ly/4eLOd29.

[33] Governo Federal. Pacto pela Transformação Ecológica entre os Três Poderes do Estado Brasileiro. 2024. Access date: October 9, 2024. bit.ly/3BHkRUg.

[34] MMA. Painel Técnico-Científico sobre Bioeconomia – 1º dia. 2024. Access date: October 9, 2024. bit.ly/4h7qb3s.

[35] MDIC. Estratégia Nacional de Bioeconomia pode ser o eixo condutor de políticas sustentáveis. 2024. Access date: October 9, 2024. bit.ly/407b2cj.

[36] They are: açaí, andiroba, babassu, baru, extractive rubber, buriti, extractive cocoa, Brazil nuts, juçara, macaúba, mangaba, murumuru, pequi, piassava, pine nuts, managed pirarucu and umbu.

[37] In ex situ conservation, genetic resources are conserved outside their natural habitat. Learn more at: Convention on Biological Diversity. Art. 2. 1992.

[38] It is the conservation of genetic resources in their natural habitats, without human interference. Learn more at: Convention on Biological Diversity. Art. 2. 1992.

[39] It is the conservation of genetic resources under human cultivation. Learn more at: Santonieri, Laura and Patricia G. Bustamante. ”Ex situ and on farm conservation of genetic resources: challenges to promote synergies and complementarities”. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi – Ciências Humanas 11, no. 3 (2016): 677-690. bit.ly/3YrbjWq.

[40] EMBRAPA. Embrapa and Acelen Renewables start macaw palm domestication for aviation fuel and bioproducts. 2024. Access date: October 9, 2024. bit.ly/4f88saw.

[41] The Bioeconomy Productive Chains Program supports the “MCTI Licuri Productive Chain” project, which has resulted in the filing of two patents by the National Center for Energy and Materials Research (CNPEM), in which the Caatinga Bioprospecting Center of the Biochemistry Department of the Federal University of Pernambuco (NBIOCAAT/UFPE) and the extractive community – the Cooperative of the Piemonte da Diamantina Region (Coopes) – are co-depositories. This achievement is unprecedented in the country and is in line with the National Bioeconomy Strategy, which aims to align scientific knowledge with traditional knowledge. Learn more at: Vialli, Andrea. “Pesquisa revela potencial dos biomas para fármacos”. Valor Econômico. 2024. Access date: October 9, 2024. bit.ly/4hbpVRk.

[42] Law no. 13,123, May 20, 2015. bit.ly/406fgBf.

[43] MDIC. Plano de Ação para Neoindustrialização 2024-2026. 2024. bit.ly/3A9Gigo.