What Is Classified as Government Spending?

The government spending analyzed in this chapter is the paid expenditure of the federal public budget, including the entire executive sphere and transfers to states and municipalities. Federal public policies are related to flows tracked in various sections of this publication, but the direct budget is highlighted for its structuring role, especially in the native forest sector. This section maps the budget disbursed by federal government ministries and agencies, related to climate objectives for the land use sector. Using this filter, the volume and profile of the federal government’s direct action on the agenda is explored.

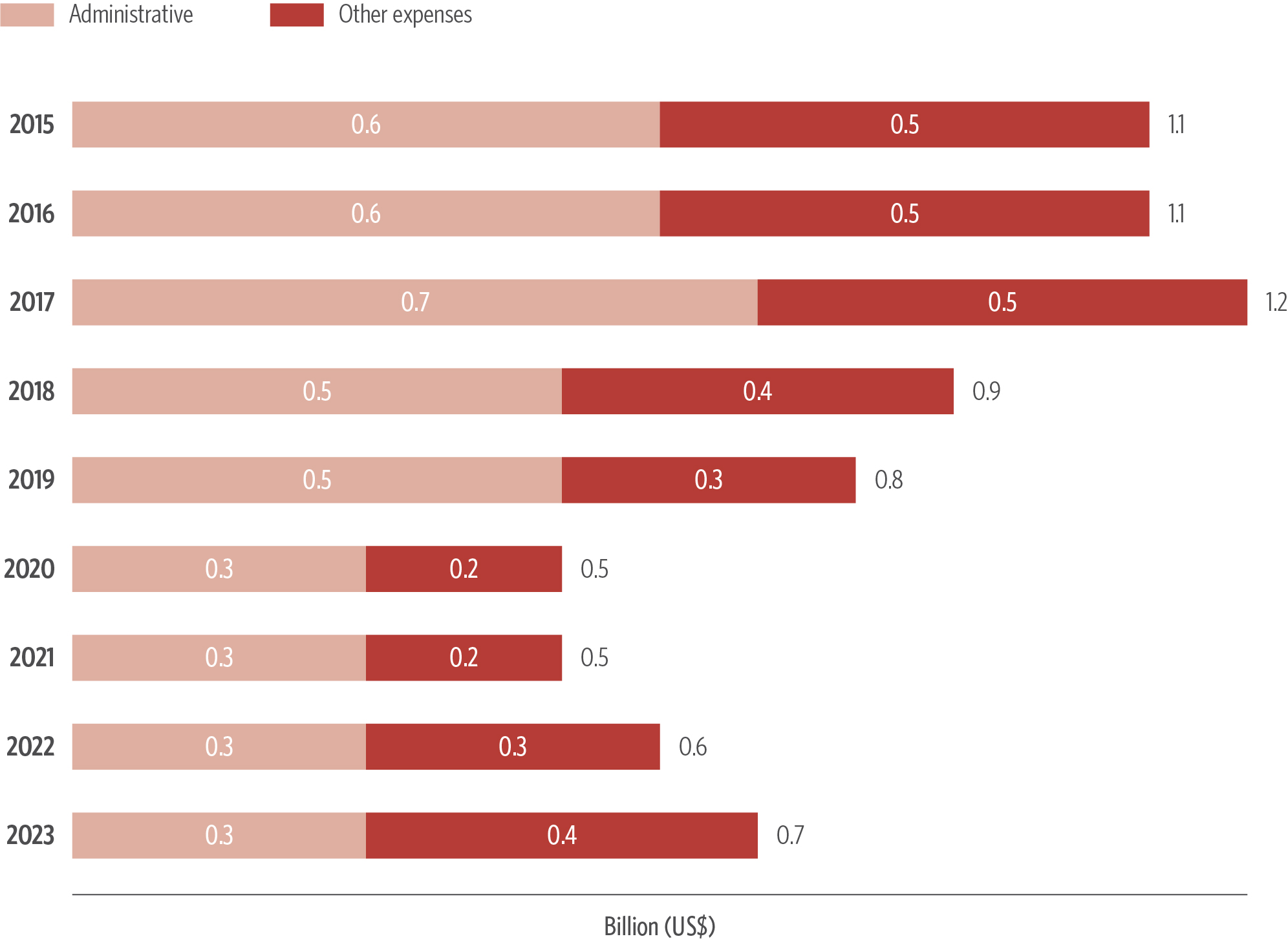

Between 2021 and 2023, federal public budget spending accounted for 3% of climate resources for land use, totaling US$ 561 million per year.[1] During this period, there was a 48% increase in flows, returning to levels seen prior to the Bolsonaro government (Figure 10). This interrupts a downward trend that had been observed since 2016, which coincided with the change of the federal executive to more liberal coalitions and the adoption of Constitutional Amendment no. 95/2016, known as the “Spending Ceiling”, which culminated in the reduction and, in certain cases, the extinction of climate-relevant government programs (IPEA 2021). Despite the change in trend, flows from government spending in the last three years are 40% lower than the average of what was tracked between 2015 and 2020.

The forest sector is responsible for 71% of these disbursements, through the work of key agencies for implementing Brazil’s climate commitments in the land use sector, which involves conservation, restoration, and reforestation actions, such as IBAMA, ICMBIO, FUNAI, MMA, the SFB and the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden Research Institute (Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro – JBRJ). These agencies are fundamental to environmental preservation and the protection of native vegetation, the fight against deforestation and fires, and the protection of indigenous peoples. For this reason, their budget was fully accounted for[2] among the climate flows tracked, including administrative expenses,[3] which accounted for 53% of the amounts in the three-year period. However, the administrative budget was stagnant between 2021 and 2023, not keeping pace with the budgetary expansion observed in the sector over the same period.

Figure 10. Climate Finance for Land Use via the Public Budget by Type of Resource, 2015-2023

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO with data from SIOP/MPO (2023), 2024

On the other hand, the effort to increase non-administrative spending by the federal executive in line with the climate was successful, with a growth of 124% between 2021 and 2023.

Water infrastructure and irrigation projects related to climate adaptation for agriculture in the northeast of Brazil represented the biggest impact on the growth of government spending between 2021 and 2023. In 2023, US$ 92 million was channeled through the Ministry of Integration and Regional Development (Ministério da Integração e do Desenvolvimento Regional – MIDR) for water supply projects, in particular the construction of adductor canals taking advantage of the transposed waters of the São Francisco River.

In 2023, spending on environmental and land regularization and land use planning, which are fundamental to the success of policies to combat deforestation, reached a peak of US$ 68 million, an increase of US$ 35 million compared to 2021. The creation, management, and implementation of federally protected areas by ICMBIO had a budget of US$ 36 million in 2023, an increase of 82% on 2021. Activities related to the demarcation, monitoring, and inspection of indigenous lands received US$ 25 million from the public budget in 2023, an increase of 249% on 2021, with FUNAI, ICMBIO, and IBAMA as the main agencies disbursing funds for these activities.

Spending on actions to prevent and control deforestation and fires had a budget of US$ 72 million in 2023, representing growth of US$ 30 million on 2021. ICMBIO’s budget for “environmental inspection and preventing and fighting forest fires” increased by US$ 25 million in 2023, 112% more than in 2021.

These activities reinforce the government’s role as one of the main financiers of Brazil’s forest sector. The public budget was responsible for two-thirds (67%) of the resources for native forests in Brazil between 2021 and 2023, with US$ 400 million per year. These government disbursements are structural for the national strategy of monitoring, preventing, and combating deforestation and fires and for promoting the conservation of native vegetation and its recovery. For this reason, it is essential to continue the climate policy and expand government programs and actions aligned with climate objectives, strengthening the aforementioned agencies to ensure concrete, long-term impacts.

National Fund for Climate Change

The National Fund for Climate Change (Fundo Nacional sobre Mudanças do Clima – FNMC)—known as the Climate Fund—is an accounting fund linked to the MMA, established by Law no. 12,114/2009 to mobilize resources for projects aimed at climate mitigation and adaptation. In December 2023, it had US$ 260 million available in funds (BNDES 2024a), which are raised through taxes from national oil companies, in addition to receiving resources from public and private institutions (CEPAL 2016). However, difficulties in accessing the fund’s resources due to tax, management, and execution issues have limited its impact (INESC 2022). During the period tracked, the Fund mobilized only US$ 30 million per year, between reimbursable and non-reimbursable modalities, of which US$ 14 million per year was related to the land use sector.

The Climate Fund operates through two modalities. The non-reimbursable modality is run by the MMA and operates through grants, mainly to subnational government projects. This modality has mobilized US$ 0.46 million per year, with US$ 0.37 million per year for land use, 86% of which went to projects in Brazil’s Northeast Region. The fund’s reimbursable modality is managed by the BNDES through low-cost credits under the Climate Fund Program, and has financed US$ 30 million per year, with US$ 14 million per year related to land use. These flows were covered in the “Capital markets and other financial instruments” section of this report because of the financial instrument used to channel these funds.

Although the amount disbursed in the tracked period is limited, the Climate Fund has great impact potential. In August 2023, the MMA and the BNDES announced reforms for the fund, relaunching it as the New Climate Fund, with a contribution of R$ 10 billion (U$$ 2 billion) to the reimbursable finance line and revising its governance model to include the participation of representatives from civil society and the private sector (MMA 2023).

[1] Budget expenditures on compensations for the PROAGRO and Crop Guarantee Fund programs are considered in the Agriculture Risk Management section and are therefore not included in this section.

[2] The budget was accounted for with the exception of pensions and precatory payments.

[3] This report consides administrative expenses as payroll, benefits for active staff and the administration.