Strict lockdowns across the globe in response to the COVID-19 crisis have led to severe economic consequences. Compared to 2019, the global GDP in 2020 fell by 4.3 %, the most severe decline since 1960 – exceeding the 0.1% drop which followed the global financial crisis in 2009 (World Bank, 2021).

While early responses to the pandemic were focused on rescue efforts, governments are now transitioning into economic recovery efforts. The two countries analyzed in this report – South Korea and Indonesia – announced stimulus packages of USD 333.7 billion and USD 74.7 billion, respectively (Climate Policy Initiative, 2021).

This study, produced in collaboration with the Seoul National University, aims to analyze the COVID-19 recovery policies in South Korea and Indonesia, particularly the role of fiscal stimulus in their energy transition goals. Both countries are actively trying to increase the share of renewable energy in their energy mix. Given the similarities in the energy supply mix and the energy market structure, this study will also explore the relationship between newly developed energy and fiscal stimulus policies and clean energy transition. It will further delve into the impact of crisis-induced fiscal spending on the trajectory of energy transition development in both countries.

This analysis is an extension to the study “Improving the impact of fiscal stimulus in Asia: An analysis of green recovery investments and opportunities” which measures the ‘greenness’ of the COVID-19 recovery packages and their contribution towards country-level climate objectives in five Asian countries.

Despite the difference in the level of electricity consumption in both countries – South Korea’s electricity consumption in 2019 was 10,192 kWh per capita, compared to Indonesia’s 972 kWh per capita – the problems faced by the energy sectors are somewhat similar. For many years, energy policies in both countries were focused on an affordable and stable supply of power to boost economic growth. As a result, the energy mix in power generation became heavily dependent on fossil fuels. However, now there is a political will to accelerate the transition to renewable energy, and both countries aim to boost renewables and reduce carbon emissions significantly. South Korea plans to increase its share of renewable electricity production to 20% by 2030 and 30-35% by 2040. Meanwhile, Indonesia aims to meet a 23% national renewable energy target by 2025. Crisis policies should ideally be in line with and support these targets.

Table: Electricity supply mix in South Korea and Indonesia by 2019

KEY FINDINGS

1. The impact of COVID-19 on the energy sectors of both countries is quite similar: In the first half of 2020, electricity consumption in both South Korea and Indonesia dropped by -2.8% and -7.06% respectively, compared to 2019.

From January to July 2020, South Korea saw a decline of -2.8% in electricity consumption compared to 2019. This decline mainly came from the industrial (-5.1%) and commercial (-1.7%) sectors and reflects an immediate response to the COVID-19 containment measures like lockdowns and an aggressive push for work/school from home. Similarly in Indonesia, from January to June 2020, electricity consumption fell by -7.06% which was again due to the industrial (-19.2%) and commercial (-18.7%) sectors. Energy consumption in the industrial and commercial sectors is expected to go back to business-as-usual once the pandemic is under control in both countries.

On the contrary, residential electricity demand increased significantly by 5.5% in South Korea and 10% in Indonesia, primarily due to restrictions that required people to stay at home for long hours.

2. The primary focus of fiscal stimulus in response to the COVID-19 crisis in South Korea and Indonesia has been to address health emergencies and to provide support to vulnerable households and businesses for survival. At the same time, South Korea managed to seize the opportunity by using the economic recovery momentum to address climate and environmental challenges.

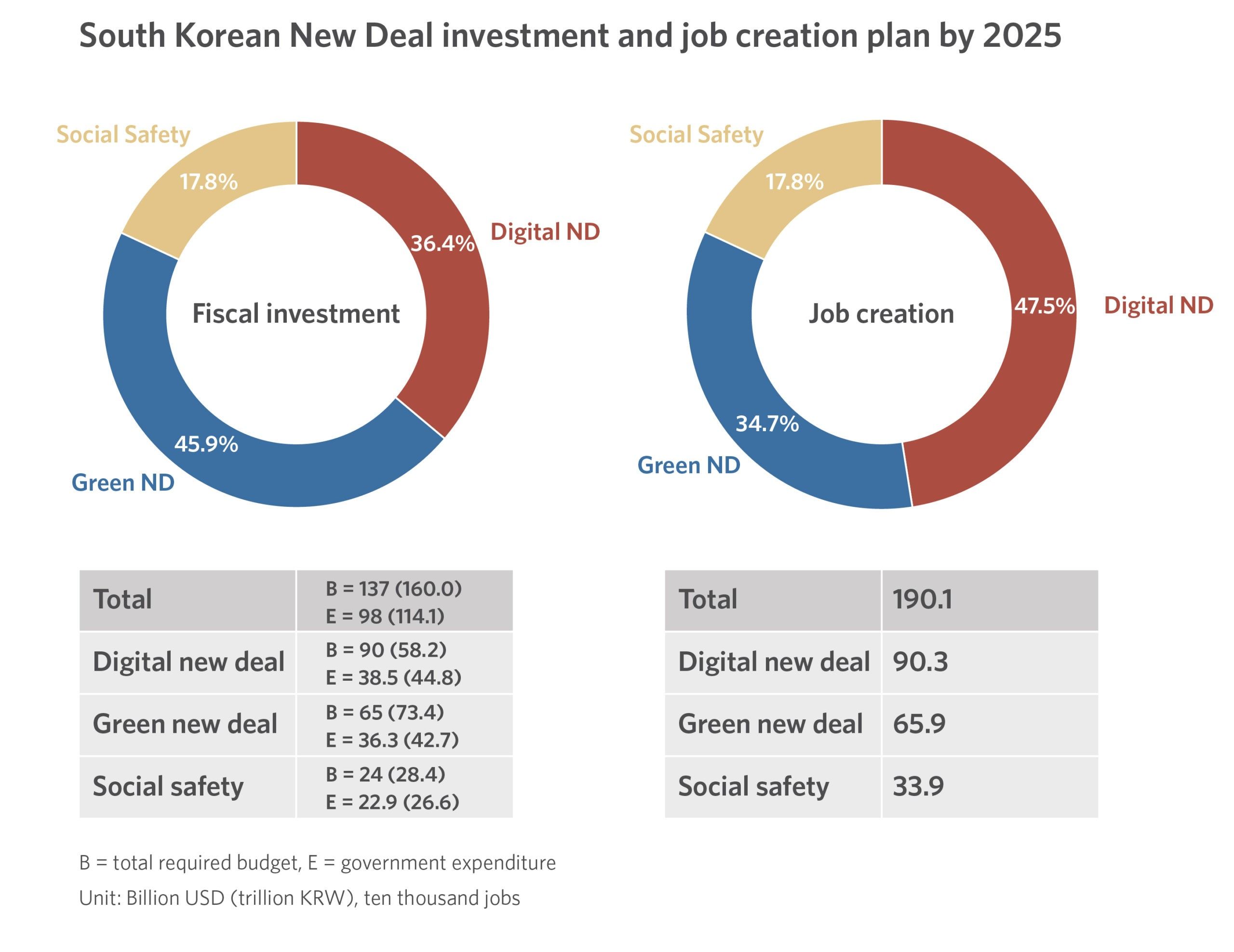

As of July 2020, the South Korean government has announced fiscal stimulus packages amounting to USD 238 billion (277 trillion KRW). It includes the South Korean New Deal (KND) equaling USD 137 billion (KRW 160 trillion) which aims to strengthen the economy by creating close to 1.9 million jobs. ln addition to the stimulus packages, the South Korean government introduced the Green New Deal (GND). The policies and projects proposed under the GND can be largely grouped into three categories: (1) transitioning buildings and infrastructure into green, (2) expansion of low-carbon and distributed energy, and (3) green industrial innovation. South Korea shows that it is possible to address both economic and climate concerns through fiscal stimulus packages. The GND, along with other recent developments, signifies a positive change of political commitment and a promising opportunity to leverage large-scale public investments for reaching long-term, sustainable growth goals.

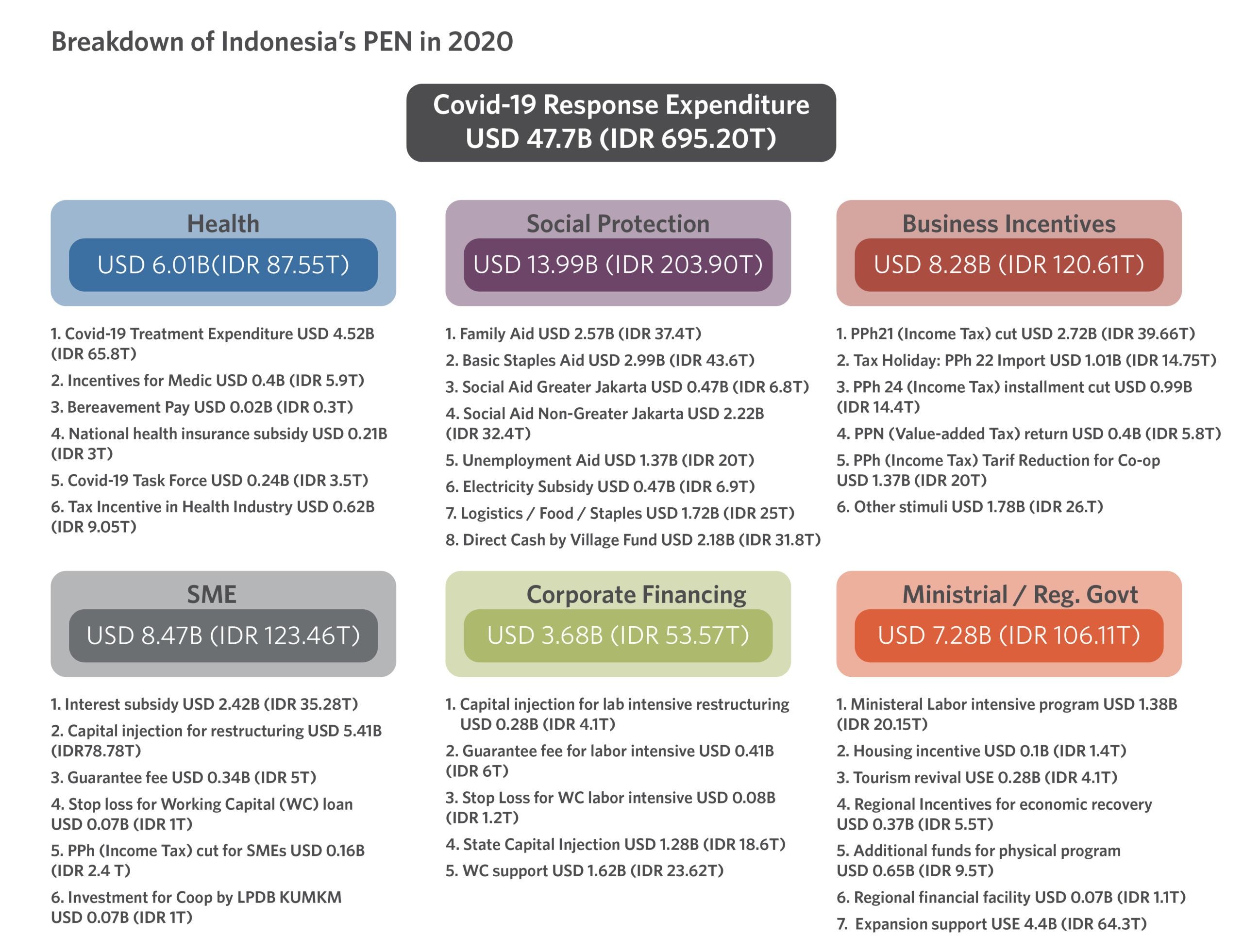

On the other hand, the Indonesian government issued a fiscal stimulus package, known as the National Economic Recovery or Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional (PEN) program, which sets out stimulus policies to soften the economic impact caused by the pandemic. PEN allocates USD 49 billion (IDR 695.2 trillion) to focus on social protection and fiscal incentives for businesses in different sectors. Allocations related to energy transition represent only 0.9% of the total PEN budget. In other words, Indonesia’s PEN does not focus on green recovery specifically. The Indonesia Planning and Development Agency (Bappenas) published recommendations to Build Forward Better, which includes the importance of clean energy for short-term and long-term economic benefits as well as better job creation than conventional energy (Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional, 2020), but these have not yet materialized into fiscal stimulus action. Overall, Indonesia’s fiscal stimulus has the potential for improvements that would support energy transition while still addressing short-term economic recovery.

3. South Korea’s Green New Deal (GND) and Indonesia’s National Economic Recovery (PEN) program both provide new impetus to the environmental and climate sectors. However, structural challenges and short-term policies jeopardize long-term sustainability.

The current energy structure and market are one of the key barriers to renewable energy transition in South Korea. Unfavorable market policies and practices have made the energy sector unattractive to private investors, which is of considerable concern considering 42% of the GND is dependent on mobilizing private investments. Therefore, policy adjustments, discussed in this report, will likely be required to ensure an increase in active participation from various private actors and prosumers ).

Undeniably, the introduction of the GND is a welcome step, but it is not without shortfalls. The deal primarily emphasizes fiscal investments and job creation, but fails to include specific targets, timelines, and plans to reduce emissions and stimulate economic recovery. By comparison, the European Green New Deal proposes new legislation that stipulates emissions reduction targets, and a revision of existing policies with more detailed plans for measurement and monitoring.

On the other hand, Indonesia’s PEN is fully financed by public fiscal spending but has addressed some potential barriers for private investment in renewable energy through financing and subsidy for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This can lower the barriers to high financing costs for renewable energy development. PEN’s direct electricity subsidy to consumers should help stabilize electricity consumption levels, which in turn will help ensure demand for renewable energy is relatively steady. However, given that allocations related to energy transition covers only 0.9% of total PEN, few barriers to private investment in clean energy can be addressed. The 2021 fiscal stimulus does not provide much comfort either, as the budget for business and tax incentive programs has declined by 15.7%, and these programs received the smallest portion with an allocation of USD 2.89 billion (IDR 47.27 trillion). This may not be helpful for small renewable energy businesses and services that still struggle with cashflow and require greater fiscal incentives to bounce back.

In conclusion, PEN is designed to address only the short-term COVID-19 impacts and is not adequate for long-term sustainability. It also fails to explicitly mention green recovery or jobs creation targets.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on our research, we recommend the following focused interventions to ensure a sustainable economic recovery and accelerate the energy transition agenda in South Korea and Indonesia:

- Stimulus spending offers a window of opportunity for both nations to support short-term economic growth while addressing longer-term climate, sustainability, and economic inclusion goals. South Korea is already on this path, but adjustments proposed in this report could increase the power of the proposed government spending by removing barriers and creating more incentives that would attract private investment. Learning from South Korea’s GND, Indonesia needs to take advantage of the economic recovery momentum to boost the long-term energy transition agenda by formalizing green recovery aspects and making green job creation more explicit within the PEN framework.

- To further ensure public spending is efficiently applied towards longer-term sustainability goals, South Korea and Indonesia’s fiscal stimulus need to include specific targets, timelines, sectoral pathways and plans to reduce emissions and stimulate economic recovery. A toolbox of policies and measures, such as reallocating subsidies to support solar PV adoption in Indonesia and revising relevant laws in South Korea to allow companies to enter into power purchase agreements with renewables providers as discussed in this report, are required to better address both short-term incentives and long-term structural changes.

- Specific attention needs to be given to create enabling environments that attract private investment in the green transition plan, while relieving the pressure on public spending. For South Korea, market policies and practices need to be reformed, while for Indonesia, better fiscal policies are needed, to address long-term investment barriers and attract private investment in both countries.