Only two of Africa’s 54 countries—Mauritius and Botswana—have investment-grade ratings of BBB- or higher[1]. Most are rated between B and CCC, representing a level of risk too high for most debt investors. This drives up the cost of capital, with CPI reporting interest rates ranging from 12.8% to 29.5% for high-emission African countries. Such prohibitive costs are a significant barrier to investment in critical climate change projects.[2]

Despite being a preferred risk mitigation tool that can increase finance mobilization by 25%, guarantees remain underutilized globally.[3]

CPI’s Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa 2024 report reveals that climate finance flows to the continent amounted to USD 44 billion in 2021/22, of which only USD 8 billion (18%) came from the private sector. What’s more, ten countries received 76% of Africa’s total private climate finance. Given the stark disparity between the continent’s climate finance requirements and existing funding, there is an urgent need for catalytic interventions to bridge the gap. Guarantees offer one such solution.

How can guarantees mobilize private climate finance in Africa?

Guarantees catalyze private climate finance by lowering risks, thereby reducing the cost of capital, strengthening local debt markets, and diversifying financial products to attract both local and international investors.

The current landscape of guarantees in Africa

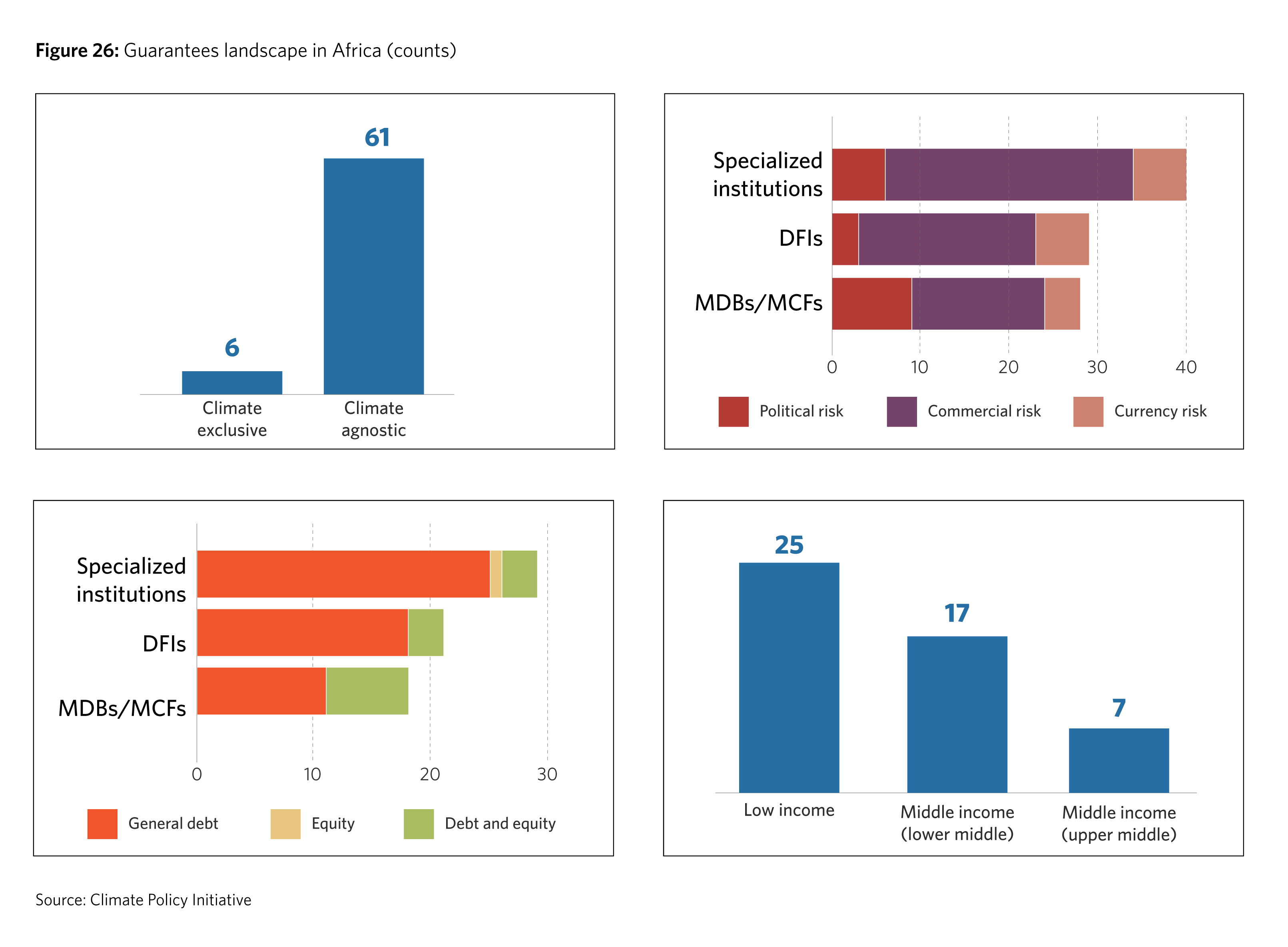

We analyzed 67 unique cross-border guarantee mechanisms that are available from 27 key entities to international debt and equity investors in Africa during June-July of 2024, yielding the six following insights:

Note: DFI= development finance institution; MDB= multilateral development bank; MCF= multilateral climate fund; Specialized institution= specialized institutions operate similarly to private sector organizations but are funded by governments and development institutions, generally focusing on guaranteeing specific types of risks in specific situations. For example, the Green Guarantee Company is the first global guarantor dedicated to providing guarantees for climate adaptation and mitigation projects in EMDEs, including Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Only six identified guarantees were exclusively targeted toward climate finance with a notable focus on renewable energy projects, highlighting an opportunity to provide more tailored climate products beyond renewable energy. In recent years, there has been a significant proliferation of climate finance instruments, which can be categorized as follows:

- Climate agnostic: Covering both climate-related and non-climate projects.

- Climate–exclusive: Dedicated to climate-specific initiatives.

Climate-exclusive guarantees are designed to address climate projects’ unique risks and financial structures, which often have high sensitivity to currency fluctuations, long lifetimes, and high capital investment requirements. By explicitly addressing these characteristics, climate-exclusive guarantees are highly effective for mobilizing climate investment, particularly in African markets. DFIs and MDBs are collaborating to launch specialized facilities to achieve climate-specific goals. For example, the African Energy Guarantee Facility[7] was launched in 2018 to enhance long-term capital for Africa’s energy sector through its investment and trade insurance services.

- Guarantees primarily focus on debt investments, reflecting the typical debt-heavy capital structures of African projects. While guarantees can mitigate risks for various actors—lenders, debt providers, and equity investors—54 of the tracked guarantees exclusively covered debt, and the remaining 13 covered both debt and equity. This is consistent across all types of guarantor institutions. For instance, specialized institutions acting as financial arms of DFIs to promote investment offered only three products that included equity investments, compared to 25 that were debt-focused.

Only one product was focused on equity, which aligns with the findings from CPI’s Africa Landscape 2024. The report shows that climate finance equity investments in Africa in 2021-2022 totaled USD 5.3 billion, compared to USD 22.3 billion in debt investments—adding to the region’s growing debt burden[8].

- Most of the guarantees analyzed cover commercial risks (63), as opposed to political (18) and currency risks (16). This is worrying given that macroeconomic risks significantly outweigh commercial risks in driving up the cost of capital for climate projects in sub-Saharan African countries, many of which face political unrest and have experienced double-digit currency depreciation over the past year. Political risks, which are unpredictable and difficult to quantify, complicate the assessments of risks and returns, thereby increasing the costs and complexity of related guarantees. Large MDBs, such as the World Bank via MIGA, remain the leading providers of political guarantees.

- There was balanced coverage of guarantee instruments between low-income (25) and middle-income African countries (24). However, some nations have more guarantee instruments than others. Among middle-income countries, guarantees are concentrated in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa. This is likely to reflect robust investment markets and strategic funding in line with the development priorities of guarantee providers in these countries. These countries also have large economies or complex financial markets that necessitate sophisticated risk mitigation tools. Among low-income countries, Mali, Mozambique, Uganda, and Rwanda have considerable guarantee coverage. This could be due to efforts to promote investments in these countries, which have progressive business environments.

- Guarantees across Africa tend to focus on the region’s key development and sustainability objectives. The high number of guarantees in the energy sector (17)—including power generation, renewables, energy efficiency, and rural electrification—reflects the key role of energy in driving regional growth. Equal attention is given to infrastructure and development, with 17 guarantees to support activities to improve transport, water, waste management, social infrastructure, and affordable housing. In contrast, agriculture and agribusiness activities received only four guarantees, indicating a limited focus on food security and climate adaptation efforts.

- There appears to be reluctance among private actors to use guarantees, despite their risk mitigation effectiveness. Some contributing factors include:

- Coverage: Partial credit guarantees cover only a portion of any loss, leaving a residual risk. In contrast, 100% guarantees can significantly accelerate private climate investment. Full guarantees are best suited for projects with potential for development but lacking immediate financial returns, or in markets where private investors are particularly risk-averse. Such full coverage should be used strategically to help build sector-wide confidence without crowding out private risk-taking.

- Barriers to using guarantees: High transaction costs, a lack of standardized pricing, limited awareness of products, and limited evidence of successful implementation discourage the use of guarantees. In addition, most guarantee instruments are not yet eligible as Official Development Assistance, creating a huge hurdle for their use in bilateral programs.

- Micro and macro risks: The effectiveness of guarantees in mobilizing private capital also depends on the underlying strength, bankability, and sustainability of project business models. It also depends on the strength of a country’s institutions, regulatory framework, and domestic capital markets. Guarantees cannot be a substitute for these fundamental elements, which are essential for the effective implementation of guarantees.

What types of guarantees are needed?

Based on the above mapping, CPI recommends the following actions to increase the uptake of guarantees in Africa:

- Increase equity guarantees: Equity investors, though accustomed to higher commercial risks, still need to hedge against political and currency risks in Africa. Making more equity guarantees available to them can also increase the flow of debt financing as investors view favorably a financial structure that has stronger equity relative to debt. Providing guarantees that cover both equity and debt can foster a more balanced and resilient financial ecosystem.

- Target high-emitting countries: We recommend providing guarantees tailored to the unique challenges of Africa’s high-emission countries—South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, and Morocco, which together account for 37% of the continent’s fossil fuel CO2 emissions. African countries face the dual demands of economic development and environmental sustainability and require tailored financial instruments to lower their risk profiles and accelerate the adoption of green technologies and practices.

- Expanding climate focused guarantees: We recommend the expansion of guarantees to climate projects, which often face specific challenges such as increased sensitivity to currency fluctuations, large capital expenditures, and long lifetimes. More tailored solutions can address these unique needs.

- Expand political and currency risk hedging: This improvement is critical to facilitate more affordable local financing options that reduce the perceived and real investment risks in African climate projects, given that their current higher cost of capital is primarily driven by macroeconomic factors, including currency risks, rather than project-specific risks[9].

[1] Brookings. 2024. Foresight Africa 2024.

[2] CPI. 2023. Cost of Capital for Renewable Energy Investments in Developing Economies.

[3] A 2022 OECD evaluation found that guarantees leveraged 25% of all mobilized private finance between 2018-2020 and were among the preferred risk mitigation tools of private investors.

See: OECD. 2022. Climate finance provided and mobilized by developed countries in 2016-2020: Insights from disaggregated analysis. OECD.

[4] World Bank. 2024. How national development financial institutions can scale green finance.

[5] CPI. 2024. Landscape of Guarantees for Climate Finance in EMDEs.

[6] Ibid

[7] A collaboration between the European Investment Bank, African Trade Insurance Agency, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), and Munich Re.

[8] CPI. 2024. Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa.

[9] CPI. 2024. Managing Currency Risk to Catalyze Climate Finance.