Various transitions have disrupted economies over the centuries. Think of the shift from horses and carts to cars or the replacement of manual laborers by machines with the automation of factories. While these brought the benefits of increased mobility and cost-effective production, they were not without their downsides.

When horsepower was displaced by automobiles, cart makers and drivers lost their livelihoods, and associated companies such as blacksmiths lost revenue. Equitability and inclusivity have not historically been key considerations during such transitions.

As we witness another major global shift – from fossil fuels to cleaner energy – large workforces across conventional electricity generation value chains stand to be affected. This time around, we have the opportunity to make the transition equitable, inclusive, and ‘just’.

India’s dependence on conventional energy sources

Large-scale fossil-fuel-based power generation infrastructure has historically been the primary energizer of India’s economy, with PSUs in this sphere acting as nation-builders. Domestic fossil fuels have also enabled the country’s energy independence, ensuring access to electricity for millions, even in remote areas.

The trends of coal production and investment in related infrastructure indicate that its consumption is set to see an upward trend in the near future despite the nation’s ambitious target of meeting 50 percent of energy requirements from renewable energy and non-fossil fuel capacity of 500 GW by 2030. However, achieving the country’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2070 will require a significant change in the national energy mix. It is expected that Solid fossil fuel use may plateau by mid of the next decade and gradually decline thereafter.

Shifting to clean energy will bring the benefits of climate change mitigation, cleaner air, and new growth industries, but will also pose economic challenges. These may be more pronounced in mineral-rich Indian states where many economic activities revolving around the mining and consumption of solid fossil fuels could be fundamentally altered. India’s central and eastern states on the Gondwana belt are at the epicenter of this. Five resource-rich eastern states of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and West Bengal together account for around 85% of the country’s solid fossil fuel production. They rely heavily on mining and downstream industries (mainly electricity generation) for economic output, employment, state revenues, and social welfare funding.

Deep Dive in Jharkhand

Jharkhand is among those most likely to face adverse short-term impacts of a low-carbon transition, as assessed in CPI’s recent Vulnerability Assessment. A subsequent CPI study highlights the significant Economic Implication for Jharkhand of the low-carbon transition, which could amount to INR 725.9 billion per year (USD 8.7 billion). While this is a gross measure, the fiscal impacts for Jharkhand would include:

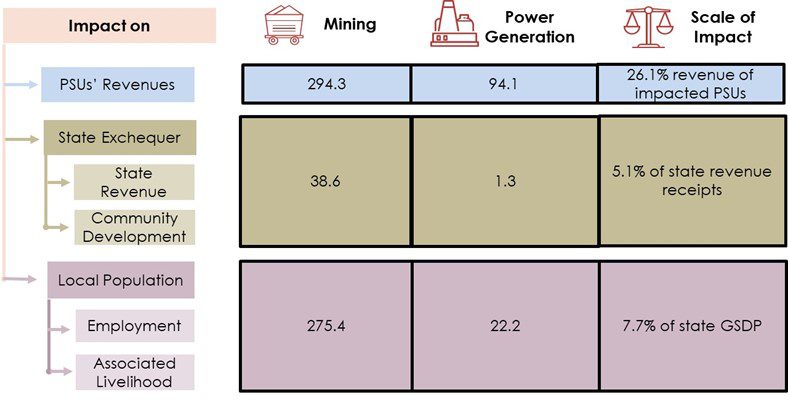

- An impact on state revenues of 5.1% of current levels.

- Loss of livelihoods could contribute to the erosion of 7.7% of the gross state domestic product (GSDP).

The transition will affect various stakeholders, including public sector undertakings (PSUs), the state government, workers across the mining and electricity generation value chain, and communities living near operations sites, as shown in the figure below.

All Figures in INR Billion and represent reduced revenue or income from a shift away from fossil fuels (INR 1 billion = USD 0.12 billion, as of Dec 2023)

As renewable energy becomes ever more cost-competitive and India moves toward its net-zero goal, Renewable rich states may start playing a bigger role in India’s energy mix which would reduce the demand for solid fossil fuel and outputs based on it. This could impact stakeholders in Jharkhand and other similar states in the following ways:

- PSUs engaged in the mining of electricity generation from solid fossil fuels will lose revenues as their offerings become less competitive in India powered by green energy. Power generators have viable options to adopt clean technologies, but mining companies may have limited avenues aside from diversification away from their core businesses.

- The State Exchequer will receive reduced tax income from PSUs and private businesses if their fossil fuel-based businesses decline. It will also face income losses from sources such as mining royalties, the District Mineral Fund Trust, cess, and transit fees. At the same time, it will also face growing social spending demands to support workers that the transition will disrupt.

- Communities living near project sites may suffer if these businesses halt their operations, as this will also see an end to their various community development programs. PSUs often carry out programs such as healthcare, educational facilities, capacity building, etc. either under mandate or to generate goodwill.

- Permanent and contractual workers in the labor-intensive mining and power generation sectors will experience acute, though differentiated, impacts related to their employment. Permanent staff may be less affected by the transition, as they may be offered employment at other sites or severance benefits, including under India’s Voluntary Retirement Scheme. On the other hand, contractual employees may lack access to such benefits, given that the country’s labor laws provide more limited support.

- Associated livelihoods (induced employment) in the local economies centered around mines and power plants will also be significantly affected by the transition. Given that many of these roles are in informal employment (e.g. hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, launderers, etc.), they may have few options for assistance from the government or PSUs. While some workers may migrate to areas where new industries or renewable energy power plants are built, this will only be possible for some. Many workers also rely on ancestral agricultural land and livestock for income and would benefit from government investment to create job opportunities in their native areas.

What needs to be done further?

Our assessment highlights that the low-carbon energy transition could significantly impact Jharkhand and other resource-rich states. Several policy and financing interventions would be needed to offset the adverse effects. Investment would be required in alternative industries and livelihoods, including large-scale workforce reskilling, job creation, and targeted social spending.

Substantial planning will be needed to develop a suitable roadmap to ensure that the transition yields benefits for all. This roadmap will need to estimate the incremental investment required each year in emerging technologies vis-à-vis the decline in stakeholders’ revenue or income from conventional resources. It will also be vital to identify the right sources of finance and develop frameworks to help finance flow to the requisite areas.

Future CPI work will examine these intricacies to identify finance requirements and sources and develop the framework that can help finance flow to make the transition just.