Brazil has a pivotal opportunity in this moment to be a global leader in sustainable agricultural production. Public policy plays a key role in defining modern agriculture and should promote the expansion of production without deforestation. Without clear guidelines, however, some policies may be misused and cause misalignment with Brazil’s environmental and climate goals.

This study reveals that subsidized rural credit has been widely channeled by various financial institutions to finance producers who allowed the destruction of native vegetation. Researchers from Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-RIO) analyzed the subsidized rural credit granted between 2020 and 2024 and provide evidence that 36% of the volume of credit contracted in the period went to properties that recorded deforestation after 2009.[1]

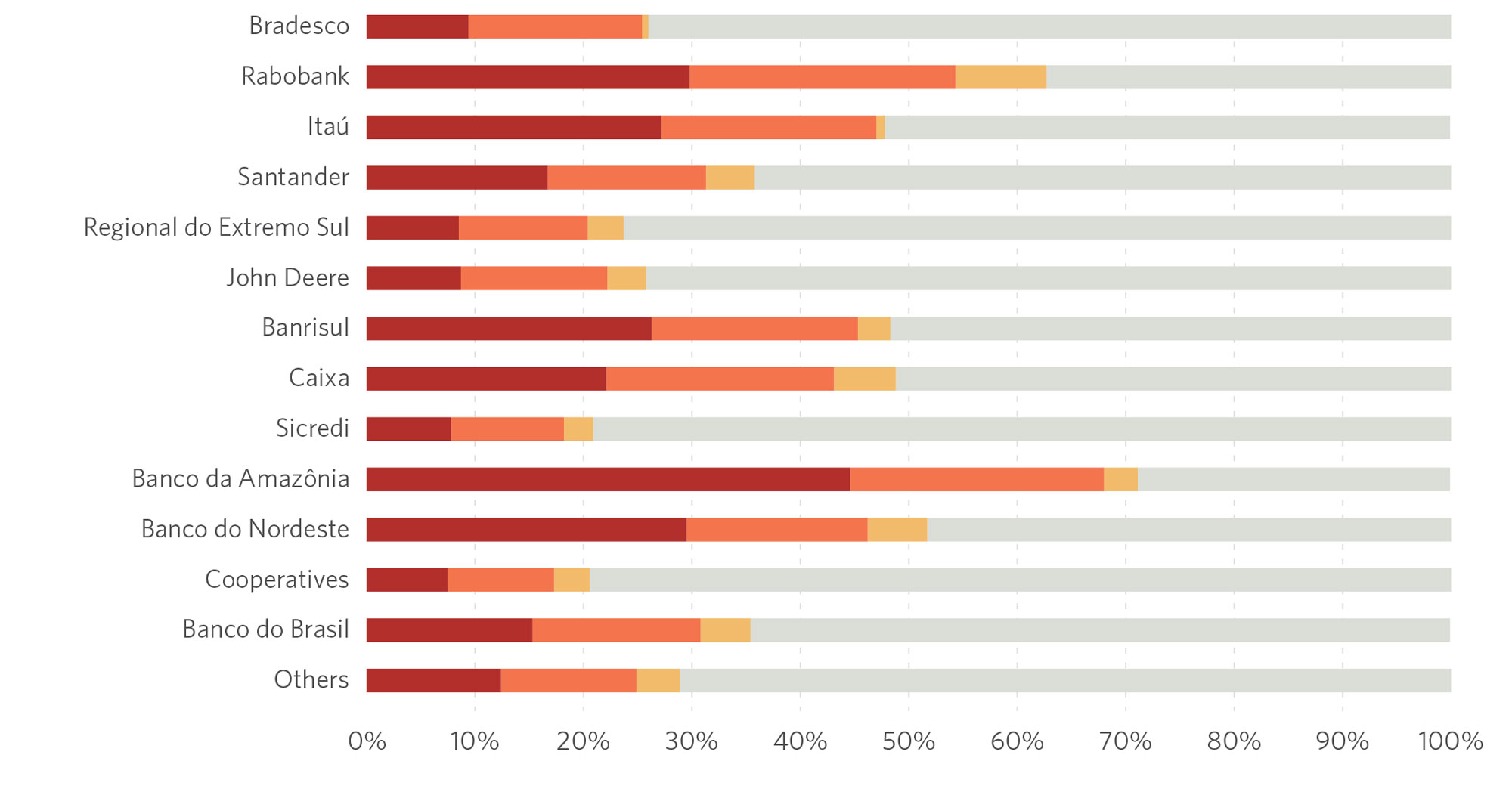

Public banks stand out as the main financial institutions granting the subsidized rural credit that has been associated with deforestation: Banco da Amazônia (BASA) manages 71% of the credit associated with deforestation, Banco do Nordeste (BNB) 52%, Caixa Econômica 49%, Banrisul with 48% and Banco do Brasil (BB) 36%. Among the private banks, Rabobank applied 63% of its subsidized rural credit to properties that saw deforestation, Itaú 48%; and Santander 36%.

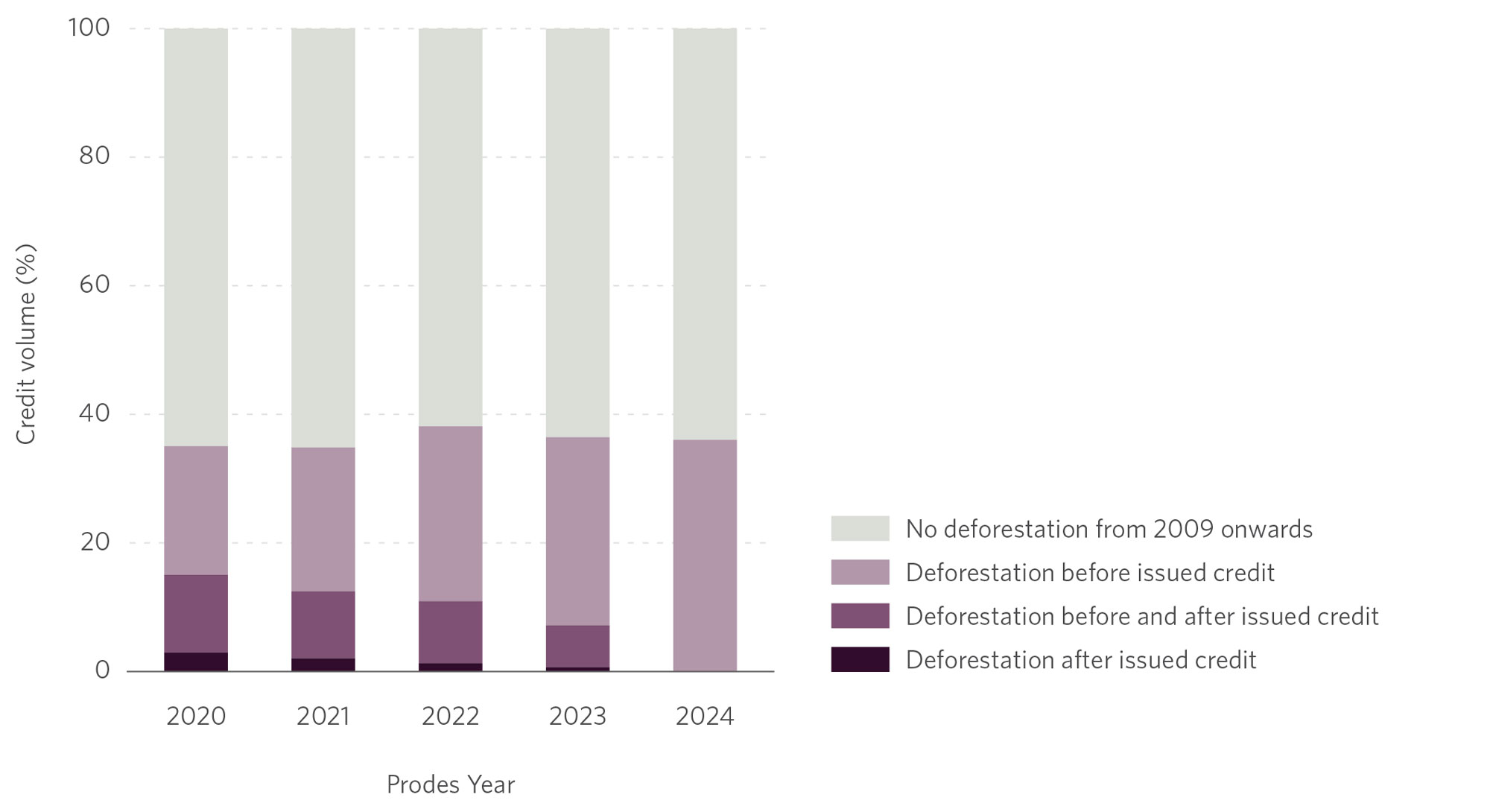

This research identifies that deforestation has occurred both before and after credit is granted. Considering the rural credit granted in 2020, 20% of the properties deforested only before the credit operation, 12% deforested both before and after, and 3% deforested only after the credit operation was granted. The analysis shows that a significant number of properties deforest on a recurring basis, potentially using the resources of the subsidized rural credit policy to finance deforestation.

Measures to prevent credit from being granted to properties with environmental embargoes for deforestation in all biomes must be instituted. In 2024-2025, the Agricultural Year Plan (the main policy instrument for the agriculture sector) made R$ 475.5 billion available for rural credit. This commitment represents significant fiscal outlays, including R$ 16.7 billion in government subsidies as well as tax benefits such as exemption from the Tax on Financial Operations. Considering this level of investment, it is essential that economic incentives promote only sustainable development and clearly dissociate subsidized credit from deforestation. This means allocating subsidized rural credit exclusively to properties with no deforestation.

Financial institutions need to be held accountable for specific sustainability objectives and must strengthen their requirements for rural credit operations. This includes analyzing the use of the land on properties that borrow rural credit, regularly checking for the presence of deforestation and requiring a Vegetation Suppression Authorization (ASV) when deforestation is identified. Restrictions on financing to properties with illegal deforestation must be a consequence.

The Rural Credit Monitor, carried out in partnership with CPI/PUC-RIO, is a significant and powerful new tool for monitoring data from the regions financed by financial institutions.[2] This platform integrates georeferenced data from the Central Bank of Brazil’s (BCB) Rural Credit and Proagro Operations System (SICOR) with deforestation data from MapBiomas Alert. Interactive maps with the location and size of the deforested area and the areas financed allow for accessible and transparent monitoring of rural credit.

Halting deforestation and promoting modern, low-carbon crops requires coordinated commitment and effort between public agencies and the financial sector, especially the banking system. Successful collaboration among these sectors will benefit the Brazilian population by maintaining vital ecosystem services provided by forests such as climate regulation, increase the competitiveness of Brazilian agribusiness in the face of growing demands from international markets and strengthen Brazil’s position as a global leader in combating climate change.

Deforestation on Properties that Access Subsidized Rural Credit

This analysis of subsidized rural credit associated with deforestation relies on the cross-referencing of three sources of information: the Rural Credit and Proagro Operations System (SICOR) of the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB), the National Rural Environmental Registry System (SICAR) of the Ministry of Management and Innovation in Public Services (MGI) and the Program for Monitoring Deforestation in the Legal Amazon by Satellite (PRODES) of the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The study considers all deforestation recorded in PRODES/INPE between 2009-2023 and the subsidized credit operations registered in SICOR/BCB contracted between August 2019-July 2024.[3] The Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural – CAR) registration number has been required in SICOR since 2019. Therefore, 2020 was the first year in which the information is complete in PRODES. Meanwhile, 2009 has been adopted as the starting point for deforestation data due to the amnesty for illegal deforestation prior to July 2008 under the 2012 Forest Code. The deforested areas were spatially cross-referenced with the polygons of properties in the CAR linked to rural credit operations, making it possible to identify the properties that both contracted subsidized rural credit and had deforestation of more than one hectare.[4]

The results show that 36% of the subsidized rural credit that was allocated between 2020-2024 was distributed to properties that have registered deforestation since 2009.[5] R$ 205.6 billion in finance for agriculture was released to these properties, out of a total of R$ 567.7 billion for which it is possible to identify the property (i.e. which have an associated CAR).[6]

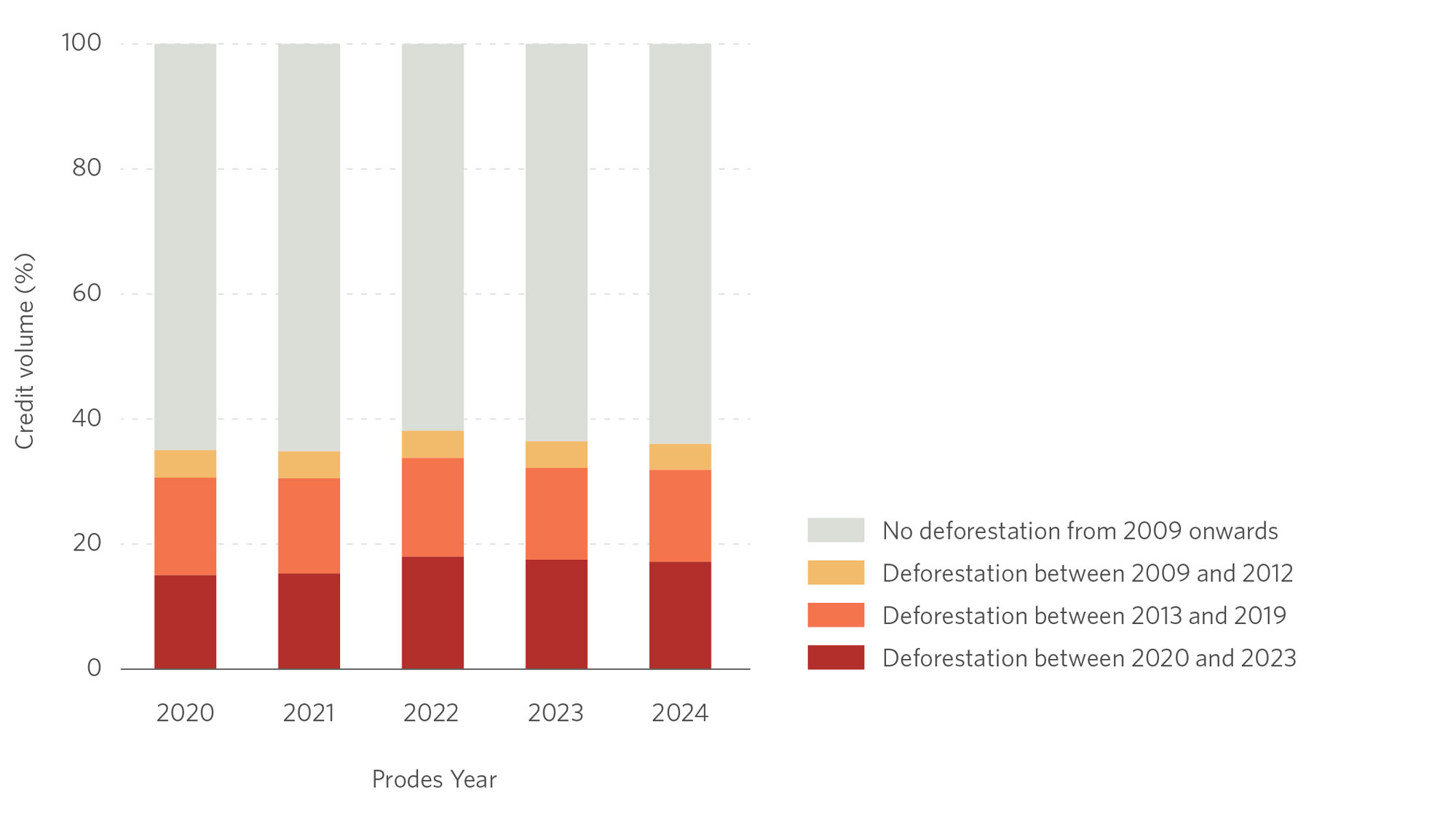

Figure 1 shows the distribution of finance contracted over the years, identifying the percentage associated with deforested areas and classifying it according to the most recent period of deforestation. Of the total volume of credit contracted in the period, 36% is associated with deforestation that has occurred since 2009. Most of the financed properties that have deforested have recent deforestation records: 17% of the credit volume is associated with properties with deforestation from 2020-2023, 15% from 2013-2019 and 4% from 2009-2012. The proportion of deforestation is stable in the period from 2020-2023.

Figure 1. Volume of Subsidized Rural Credit on Rural Properties by Year of Deforestation, 2020-2024

Note: The figure takes into account credit operations registered between August of the previous year and July of the reference year (on the horizontal axis) to make it compatible with the PRODES year, which is the source for deforestation data. The most recent record of deforestation overlapping with the CAR that took credit is considered. Only credit operations with an associated CAR are considered.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO based on data from SICOR/BCB (2020-2024), PRODES/INPE (2009-2023) and SICAR (2023), 2024

From 2020-2024, the volume of subsidized resources earmarked for properties with deforestation increased from R$30.6 billion to R$47.6 billion, representing a growth of 56%. This percentage exceeds the increase in total subsidized rural credit resources linked to a CAR, which grew from R$87.2 billion to R$132.1 billion, an increase of 51%. Part of this increase indicates an expansion of resources allocated to rural credit policy during the period; it also reflects a rise in the number of operations that have started reporting the CAR.[7]

Figure 2 shows deforestation in relation to the time period when the subsidized rural credit was allocated. Most of the deforestation associated with the credit was recorded before the credit was distributed, which is partly due to the fact that deforestation has been observed since 2009 and ends in 2023, while the credit operations considered begin in 2020 and take into account a year for which deforestation data was not yet available, 2024. Despite this, the proportion of credit associated with properties that registered deforestation after the funds were released is significant: 8.4%, considering those that only deforested afterwards (1.2%) and those that deforested before and afterwards (7.2%). This analysis reveals that a significant proportion of properties deforest on a recurring basis, possibly using subsidized rural credit resources to finance deforestation.

Figure 2. Volume of Subsidized Credit on Properties by Chronology of Occurrence of Deforestation in Relation to Credit Taken Out, 2020-2024

Note: The figure takes into account credit operations registered between August of the previous year and July of the reference year (on the horizontal axis) to make it compatible with the PRODES year, which is the source for deforestation data. The most recent record of deforestation overlapping with the CAR that took credit is considered. Only credit operations with an associated CAR are considered.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO based on data from SICOR/BCB (2020-2024), PRODES/INPE (2009-2023) and SICAR (2023), 2024

The volume of credit associated with deforestation is considerably higher when the analysis considers the total areas of the properties (CARs) compared to the areas of the financed projects (plots). Using only the deforestation in the 2020-2023 period, the proportion of the volume of credit associated with properties with deforestation (17%) is higher than the volume of credit associated with these plots with deforestation alerts in the same period (7%).[8],[9] The difference stems from two factors: 1) The area of the property (CAR) tends to be larger than the area of the enterprise; 2) As the financed plots are self-declared, producers have an incentive to declare areas that are already open to avoid problems with monitoring. With the CAR, this practice is more difficult, although it is still possible to avoid existing restrictions by changing the polygon boundary or creating a new CAR registration to access the rural credit policy if the property has any social, environmental or climatic restrictions.

28% of properties that deforested after 2009 took out subsidized rural credit between 2020-2024. This figure would be even higher if it were possible to observe the CAR for all subsidized rural credit operations (some operations do not have an associated CAR) and if we included operations prior to 2019. Tackling the problem of deforestation requires susbstantial work decoupling rural credit from deforestation activities.

Financial Institutions and Subsidized Credit Associated with Deforestation

Financial institutions are key players in implementing rural credit policy in Brazil. They provide financing directly to producers and they are responsible for the distribution of public resources (either through direct subsidies to equalize interest rates on specific lines of credit or through public sources of finance such as tax revenue from the Constitutional Financing Funds). In addition, rural credit has tax benefits, such as exemption from the Tax on Financial Operations[10] and exemption from income tax for the Agribusiness Credit Bill (LCA), one of the main sources of funds. This means that even free credit (which is not directed by public policy) has government benefits and draws resources from Brazilian society. For these reasons, financial institutions must monitor their portfolios and adopt measures to dissociate their operations from activities that destroy native vegetation.

In addition to the public interest, it is in the interest of financial agents that their activities are not linked to businesses that pose risks to their core business or reputation. The National Monetary Council (CMN) establishes that actions to ensure compliance with the Social, Environmental and Climate Responsibility Policy (PRSAC) of financial institutions “must be continuously monitored and evaluated as to their contribution to the effectiveness” of the policy.[11] In fact, many financial institutions explicitly place the issue of deforestation in their PRSACs or related documents, as detailed in Box 1.

Box 1. The Social, Environmental and Climate Responsibility Policies of Financial Institutions

This box highlights how the main financial institutions that channel rural credit address deforestation in their PRSACs or related documents:

1. Banco do Brasil (BB) has adopted a target of zero illegal deforestation in its finances and mentions checking for plots overlapping with deforestation alerts and signs of illegality from the MapBiomas Alerta platform; it pledges to interrupt the contracting process if an overlap is observed.[12]

2. The Banco do Nordeste (BNB) mentions the adoption of mechanisms to prevent illegal deforestation in its finance, including the verification of authorizations for legal deforestation.[13]

3. The Banco da Amazônia (BASA) states that it is forbidden to finance “agricultural areas with deforestation practices” and “agriculture activities in illegally deforested areas of the property.”[14]

4. Sicredi reports a pre-credit validation procedure in which an alert is issued when there is an overlap with deforested areas. However, operations are only halted when they do not comply with CMN or BNDES rules, in the case of funds transferred by the bank.[15]

5. Caixa says it checks whether the rural property has a deforestation alert based on a technical cooperation agreement signed with MapBiomas. When the removal of vegetation does not have proven authorization from the competent body, the proposal is not included in the credit chain.[16]

6. Banrisul mentions combating irregular deforestation in its PRSAC, but does not provide any specific measures beyond what is required by CMN rules.[17]

7. Santander claims that it monitors deforestation in 100% of the properties financed by the bank or given as collateral, using official data and the MapBiomas platform. If any irregularities are detected, the bank states it will demand an explanation from the client. The bank also claims to have a public target of eliminating illegal deforestation in the meat production by 2025.[18]

8. Itaú mentions the satellite monitoring of properties that access credit from the bank, stating that the detection of illegal deforestation can lead to the contract being canceled or terminated early. It also highlights the meat production.[19]

9. Rabobank Brazil mentions the exclusion of clients convicted of illegal deforestation and explicitly states that it does not grant finance for the purpose of carrying out deforestation, even if legally authorized.[20]

10. Bradesco highlights restrictive measures for activities with infractions related to illegal deforestation in its PRSAC.[21] It also calls attention to its commitment to zero illegal deforestation in the meat production by 2025.[22]

Most financial institutions point out that only illegal deforestation is considered a justification for blocking operations, even if all deforestation is monitored. In this study, we analyzed both legal and illegal deforestation, which allows us to broadly assess the degree of exposure of financial institutions. Identifying signs of irregularity should be done on the basis of documentary evidence, which is beyond the scope of this analysis. However, as rural credit relies on government subsidies, tax exemptions and targeting, it is essential that public resources are aligned with the interests of Brazilian society, such as the commitment to zero deforestation and achieving environmental and climate goals.

The Rural Credit Monitor, launched by MapBiomas in partnership with CPI/PUC-RIO, can facilitate the monitoring actions of financial institutions, allowing them to identify enterprises associated with deforestation. This information can be used as an indicator of compliance with their policies. In addition to the areas financed in the project, the MapBiomas Alert platform also allows deforestation to be verified in the area of the property registered in each CAR based on the property code.

In order to take stock of the financial institutions’ agribusiness portfolios, the following analysis presents the association between subsidized rural credit and deforestation by financial agent. For the sake of simplicity, our analysis focuses on the credit operations released during the last PRODES year (August 2023-July 2024) and examines the deforestation that has occurred since 2009 on the properties associated with these operations.

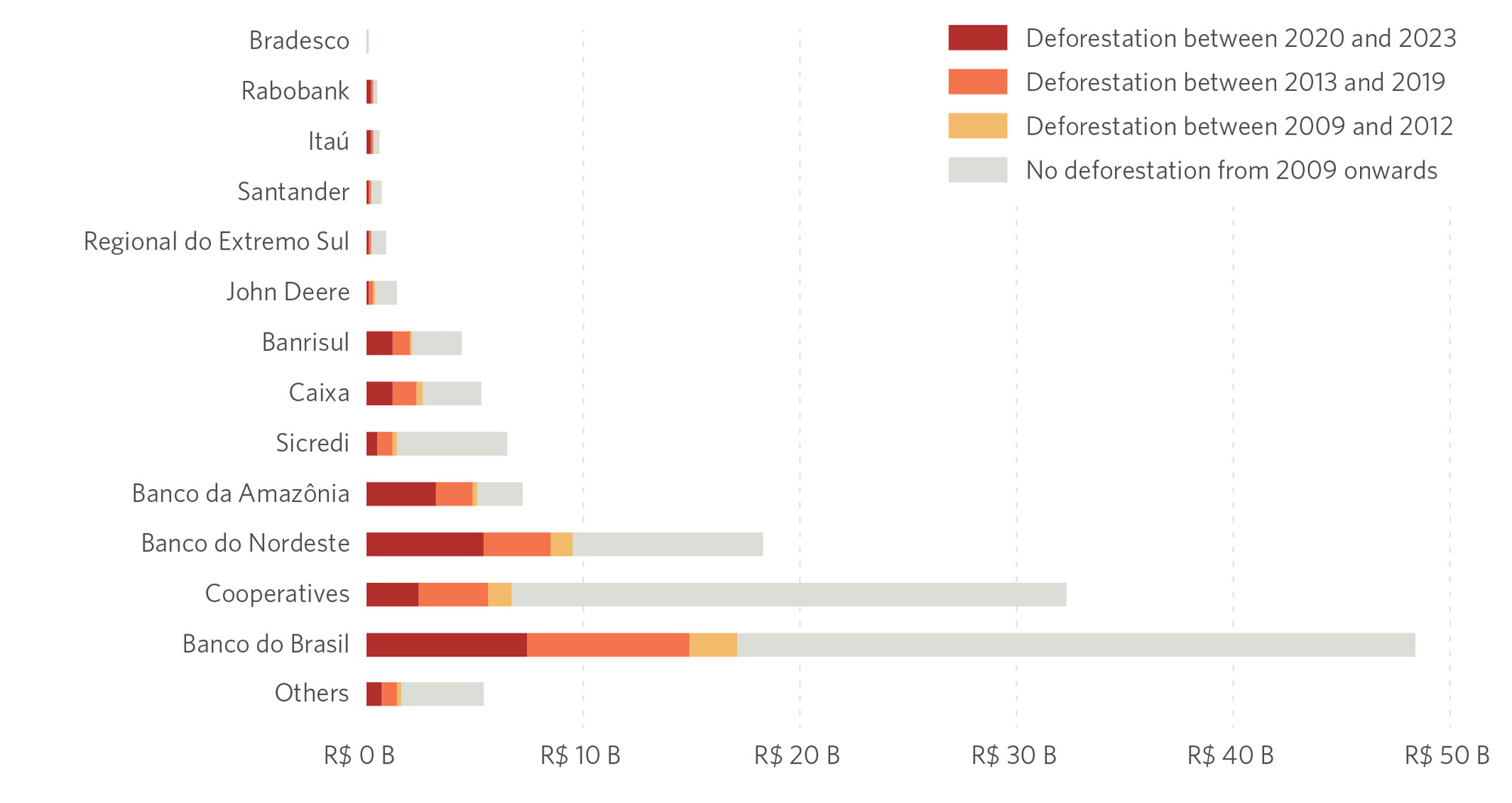

Public banks and credit cooperatives finance 91% of the volume of subsidized rural credit associated with deforestation. Figure 3a shows the absolute amounts per financial institution. From August 2023-July 2024, R$ 132.1 billion in subsidized rural credit was released for operations with associated CAR, of which R$ 47.6 billion (36%) went to properties with deforestation registered after 2009. Of this amount, R$ 43.4 billion was granted by public banks and cooperatives.[23]

Banco da Amazônia and Banco do Nordeste are the financial institutions holding the greatest percentage of properties that deforest within their subsidized rural credit portfolio (Banco da Amazônia 70.8%, Banco do Nordeste 51.9%). In addition, these banks’ operations are located in areas of the most recent deforestation (such as the arc of deforestation in the Amazon and the Matopiba region, which includes the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia). These banks are also among the main operators of credit financed with FCF resources, and do not follow the same rules as the Rural Credit Manual (MCR). Other public banks also provide a considerable amount of subsidized rural credit for properties with deforestation: Caixa Econômica (49%), Banrisul (48%) and Banco do Brasil (36%).

Private banks operate a smaller amount of resources, but also show a high level of deforestation occurring within their portfolios. Rabobank has 63% of its subsidized rural credit invested in properties that have deforested, Itaú has 48% and Santander 36%.

Figure 3. Volume of Subsidized Credit for Rural Properties by Year of Deforestation and Financial Institution, 2024

3a. Absolute Values in R$ Billion

3b. Relative Values (% total of each financial institution)

Note: The figure takes into account credit operations registered between August 2023-July 2024 to make them compatible with the PRODES year, which is the reference for deforestation data. The most recent record of deforestation overlapping with the CAR that took credit is considered. Only credit operations with an associated CAR are considered.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO based on data from SICOR/BCB (2024), PRODES/INPE (2009-2023) and SICAR (2023), 2024

Public Policy Implications

It is essential for the allocation of public resources in rural credit to be transparent and for public agencies to ensure that those resources are prioritized for rural producers who adopt sustainable practices and do not deforest their properties. Rural credit policy can make a significant contribution to meeting the country’s environmental and climate goals, which include conserving forests and reducing carbon emissions from land use.

The analysis in this paper is based on the regulations in force. CMN Resolution 5081/2023 defined the social, environmental and climatic impediments to accessing rural credit, using the rural property as a whole as the unit of analysis and not just the area of the enterprise associated with the credit.[24] This applies, for example, to the detection of embargoes for illegal deforestation and the analysis of overlaps with protected public lands. This prevents the borrower, when disclosing the land for financing, from registering geodesic coordinates that leave out exactly the area that could cause a blockage in credit. In addition, there are credit operations that do not need to report the area of the project, but still need to report the CAR where the funds will be invested. It is essential to consider the entire property and not just the area financed.

Advances in rural credit policy in recent years have increased both the restrictions on producers who do not comply with certain socio-environmental safeguards and the incentives for producers who adopt good agriculture practices. However, there is still a long way to go. Although the list of social, environmental and climatic considerations has been expanded, the only enforceable regulation in rural credit regarding deforestation is the implementation of environmental embargoes, which capture just a small part of deforestation.[25],[26] Even this has met with resistance.[27]

Fortunately, the technology to enhance the detection and monitoring of deforestation has advanced rapidly and offers important data about the properties that take out rural credit. In this context, financial institutions play a crucial role in monitoring their operations. Tools such as the Rural Credit Monitor contribute significantly to this process, reducing monitoring costs for financial agents.

A crucial first step is to ensure that rural credit is not allowed to be used to finance properties that have been subjected to illegal deforestation. Once vegetation suppression has been detected, an ASV or equivalent document should be required to prove that the deforestation is legal. If the documentation is not presented or there are any irregularities, the credit can be blocked or paid out early.[28] This documentation process should be required both before the funds are released, ensuring that the properties to be financed do not include areas that have already been illegally deforested (regardless of whether there is an embargo in place), and after the funds have been released. This record will help dissociate rural credit from promoting illegal deforestation, as well as to assess the extent to which financial institutions are effectively complying with what they declare in their PRSACs.

We need to go further. Brazil has set a climate target of zero deforestation by 2030. As shown in this study, there is strong evidence of a substantial link between deforestation and subsidized credit in Brazil. In order to meet the country’s zero deforestation target, it is necessary to completely dissociate subsidized rural credit distribution from any form of deforestation. Economic incentives should promote sustainable development and encourage practices in line with environmental conservation. Subsidies, tax benefits and other expenditures of public resources need to be directed towards producers who contribute to tackling the environmental and climate crisis. Public policy and financial agents each play a crucial role in advancing Brazil’s environmental goals.

Methodology

This study extends the analysis of the previous CPI/PUC-RIO publication “CAR to CAR: The Relationship Between Subsidized Rural Credit and Deforestation”, published in July 2024.[29] The universe of analysis was expanded in two ways compared to the previous study. All of the subsidized rural credit operations with a CAR registration number in SICOR/BCB as of the 2020 PRODES year are included,[30] which adds two years of rural credit contracting to the analysis.[31] In addition, the entire horizon of deforestation increases reported by the PRODES/INPE system from 2009-2023 is incorporated (this represents the latest update available at the time the study was prepared).[32] The PRODES/INPE data was spatially cross-referenced with the geometries of the CARs from SICAR/MGI to identify all of the properties that overlapped the deforestation polygons. The data from SICOR/BCB and SICAR/MGI was matched using the property code associated with the credit operations.

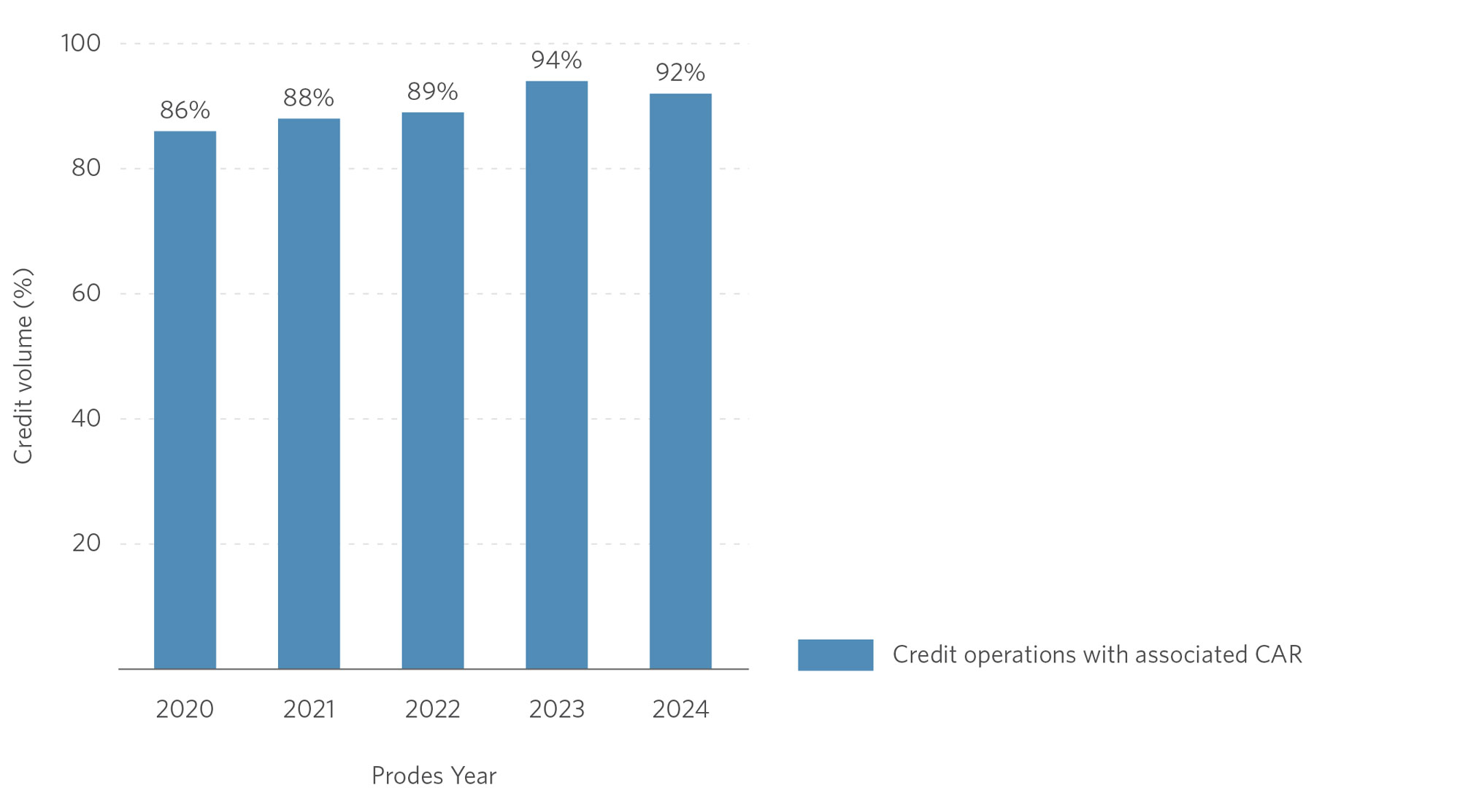

SICOR/BCB’s public microdata contains information on the location of the enterprise only for credit operations employing equalization of interest rates, access to public sources of funds or which are supported by the Agriculture Guarantee Program (PROAGRO). Not all credit operations have an associated CAR in SICAR/MGI, either because they are not obliged to report the CAR in SICOR/BCB or because the property is not registered in SICAR/MGI at the time of analysis. Extraction from SICAR/MGI is fixed in time, so some CARs that were active at the time of the credit operation may no longer be active at the time of extraction.[33] Figure 4 shows the percentage of credit operations in which it was possible to obtain at least one associated CAR number over the years. All CARs available on SICAR/MGI were included, with no restrictions as to status or type.[34]

Figure 4. Volume of Subsidized Rural Credit with Associated CAR, 2020-2024

Note: The figure displays credit operations registered between August of the previous year and July of the reference year (on the horizontal axis) to make it compatible with the PRODES year, which is the source for deforestation data.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO based on data from SICOR/BCB (2020-2024) and SICAR (2023), 2024

The deforestation polygons analyzed represent the annual increases detected by PRODES/INPE in all Brazilian biomes. Polygons of vegetation suppression with an area greater than 1 hectare were included. In the Amazon, deforestation records in areas of non-forest native vegetation were also taken into account. The dates of the PRODES/INPE deforestation maps vary by biome. In the Amazon, we have observed increases in deforestation for each year since 2008. To make it compatible with the cut-off date of the Forest Code (Law No. 12.651/2012), July 22, 2008, only deforestation from 2009 onwards was considered in this analysis.

In this analysis, an association between rural credit and deforestation is considered whenever a property (CAR) linked to a rural credit operation with subsidized resources has an intersection of more than one hectare with a deforestation polygon from the PRODES/INPE database, regardless of the date the credit was contracted. Thus, these properties include both those that carried out deforestation before the credit was obtained and those that registered deforestation after the credit was contracted.

The same property can have deforestation records for different years. To assign a certain amount of credit to a specific year of deforestation (as in the case of Figure 1), the most recent year of deforestation is considered. Thus, if the last year of deforestation was after the credit was taken out, this operation will appear in the 2020-2023 group, but this does not mean that this property did not also deforest before.

There are operations registered in SICOR/BCB with more than one property linked, but it is not possible to determine the portion of the credit attributed to each one. Therefore, for operations with more than one CAR linked, the CAR with the largest area was considered to be the operation’s main CAR. If this CAR has registered deforestation, the entire operation is considered to be associated with deforestation. Only 6% of rural credit operations have more than one CAR record, and filtering out just one CAR per operation eliminates 6.5% of the CAR codes that received subsidized rural credit in the period. It is possible that the records discarded from an operation have a record of deforestation and the largest CAR in the operation does not, so the figure presented in this study is a lower bound on the total volume of subsidized rural credit associated with deforestation.

All the monetary values presented in the study were deflated based on the Broad Consumer Price Index (IPCA), produced by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). The reference period was July 2024, the most recent month of the PRODES 2023 year.

The authors would like to thank Laura Lago and Rogério Reis de Mello Filho for research assistance and the comments and suggestions from Juliano Assunção and Natalie Hoover El Rashidy. We would also like to thank Sarah Robbins, Giovanna de Miranda, and Camila Calado for editing and revising the text and Meyrele Nascimento, Nina Oswald Vieira and Julia Berry for formatting and graphic design. We would like to thank the MapBiomas initiative for its partnership in the development of the Rural Credit Monitor platform, as well as for the valuable exchanges.

[1] This analysis uses the PRODES years, which cover the period between August of the previous year and July of the reference year. The 2009 PRODES year (which began in August 2008) is used as the benchmark for deforestation data because the 2012 Forest Code granted amnesty for illegal deforestation that took place up until July 2008, provided that specific conditions for regularization were met. Deforestation that took place after that date remains subject to the penalties provided for in current environmental legislation.

[2] To learn out more about the platform, visit: MapBiomas. Crédito Rural. 2024. bit.ly/4iplTW0.

[3] Deforestation data is published by PRODES year, which covers the period from August of the previous year to July of the reference year. As it is not possible to adjust this period, rural credit operations were assigned to the corresponding PRODES years considering the start date of the operation.

[4] For more information, see the methodology section at the end of the document.

[5] This figure is higher than the 15% found in a previous CPI/PUC-RIO publication because the period of analysis is longer in terms of both credit operations and deforestation. For more information, see the methodology section. The previous publication can be accessed at: Mourão, João, Mariana Stussi and Priscila Souza. Credit Where It’s Due: Unearthing the Relationship between Rural Credit Subsidies and Deforestation. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2024. bit.ly/CreditDeforestation.

[6] Another R$61.1 billion has no associated CAR registrations, totaling R$628.9 billion in subsidized rural credit resources in the period analyzed. The figures are adjusted for inflation. For more information, see the methodology section.

[7] For more information, see the Methodology section.

[8] Note that for the 17%, the denominator is the total volume of subsidized credit in operations with associated CAR, while for the 7%, the denominator is the total volume of subsidized credit in operations that report geodetic coordinates for the plots being financed. Not all operations with an associated CAR need to declare plots.

[9] This value was calculated by cross-referencing the geodesic coordinates of the enterprises associated with the credit (financed plots) with the deforestation alerts from MapBiomas Alerta, following the methodology of the Rural Credit Monitor.

[10] Item IV of Art. 8 of Decree no. 6.306/2007. bit.ly/3OJIS0a.

[11] Art. 4 of CMN Resolution no. 4,945/2021. bit.ly/3ZIyOLr.

[12] Banco do Brasil. Relatório Anual 2023. 2024. bit.ly/49lWN66. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[13] Banco do Nordeste. Política de Responsabilidade Social, Ambiental e Climática do Banco do Nordeste. 2024. bit.ly/3ZB63Qu. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[14] Banco da Amazônia. Relatório de Riscos e oportunidades Sociais, Ambientais e Climáticas – RELATÓRIO GRSAC – Junho 2023. bit.ly/4ilGZ7r. 2023. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[15] Sicredi. Relatório de Sustentabilidade 2023. 2024. bit.ly/4fVIJ5L. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[16] Caixa Econômica Federal. Relatório de Sustentabilidade 2023. 2024. bit.ly/49jfWWt. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[17] Banrisul. Política de Responsabilidade Social, Ambiental e Climática – PRSAC. 2024. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[18] Santander. Relatório Anual Integrado 2023. 2024. bit.ly/4fX7KO8. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[19] Itaú. Relatório ESG 2023. 2024. bit.ly/3ZBfwr3. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[20] Rabobank. Política de Responsabilidade Social, Ambiental e Climática (PRSAC). 2024. bit.ly/4in7fhO. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[21] Bradesco. Norma de Responsabilidade Social, Ambiental e Climática. 2023. bit.ly/3OG5dvA. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[22] Bradesco. Relatório ESG 2023. 2024. bit.ly/3Vm82Wq. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[23] Credit cooperatives are associations of rural producers who come together to collectively meet their finance needs. Some examples are Credicitrus, Credicoamo and Cresol. Another category of financial institutions are cooperative banks, which usually operate on a larger scale and serve clients who are not cooperative members, as is the case with Sicredi and Sicoob.

[24] The only exception to this rule is the provision that deals with impediments in areas located on land occupied by quilombola communities (MCR 2-9-6), in which the project still remains the current criterion for applying the restriction.

[25] A previous CPI/PUC-RIO study found that less than 5% of the area of new deforestation has been embargoed in recent years. A significant portion of the deforested area is therefore unrestricted and eligible for rural credit, including subsidized credit. The previous publication can be accessed at: Mourão, João, Mariana Stussi and Priscila Souza. Credit Where It’s Due: Unearthing the Relationship between Rural Credit Subsidies and Deforestation. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2024. bit.ly/CreditDeforestation.

[26] It is possible to expand the understanding of the current regulation by establishing that the impediment due to an embargo is at the level of the client (borrower) and not the property, recognizing the fact that the beneficiary of thwe public policy is the rural producer and not the land. Thus, any credit operation requested by someone who has an embargo on any of their properties would be blocked. This has been the BNDES’ understanding since March 2024. More information at: BNDES. SUP/ADIG Circular No. 76/2023. 2023. bit.ly/41a04Dv. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[27] More information at: Assunção and Oliveira. O futuro do crédito rural e o respeito à legislação brasileira. 2024. bit.ly/3ODPo8M. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[28] The National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) has already been applying this logic since February 2023 in its automatic indirect operations, using the MapBiomas Alert Platform for this purpose. More information at: BNDES. Circular SUP/ADIG nº 57/2022. 2022. bit.ly/4g96IhM. Access date: November 26, 2024.

[29] Mourão, João, Mariana Stussi, and Priscila Souza. Credit Where It’s Due: Unearthing the Relationship between Rural Credit Subsidies and Deforestation. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2024. bit.ly/CreditDeforestation.

[30] The PRODES year refers to the period between August of the previous year and July of the reference year.

[31] A CAR registration number has been required for Sicor since 2019; 2020 was the first PRODES year in which this information is complete. For this study, all subsidized rural credit operations contracted from August 2019 to October 16, 2024 (the date the database was extracted for the study), were considered. Operations contracted between August-October 2024, which correspond to the PRODES 2025 year, were excluded from the analysis in order to consider only complete years.

[32] The polygons used were those where vegetation was cleared over an area of more than 1 hectare in all biomes. To do this, we used data on annual deforestation increases for all biomes and for the Amazon we also considered deforestation in non-forest areas.

[33] The Sicar/MGI extract used in this analysis dates from November 2023.

[34] The CARs are divided into three categories: Rural Property (IRU), Settlement (AST) and Traditional Peoples and Communities (PCT). All were considered in this analysis.