Agrifood systems form the cornerstones of economies, societies, and ecosystems across the world, but also generate significant environmental costs. Agrifood systems are currently responsible for a third of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—second only to energy systems. They are also the primary source of nitrous oxide and methane emissions, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and freshwater consumption globally. In addition, these systems are both already being impacted and highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change: rising temperatures, floods, storms, droughts, and other extreme weather events that are already, and will continue to, severely reduce agricultural productivity and disrupt supply chains.

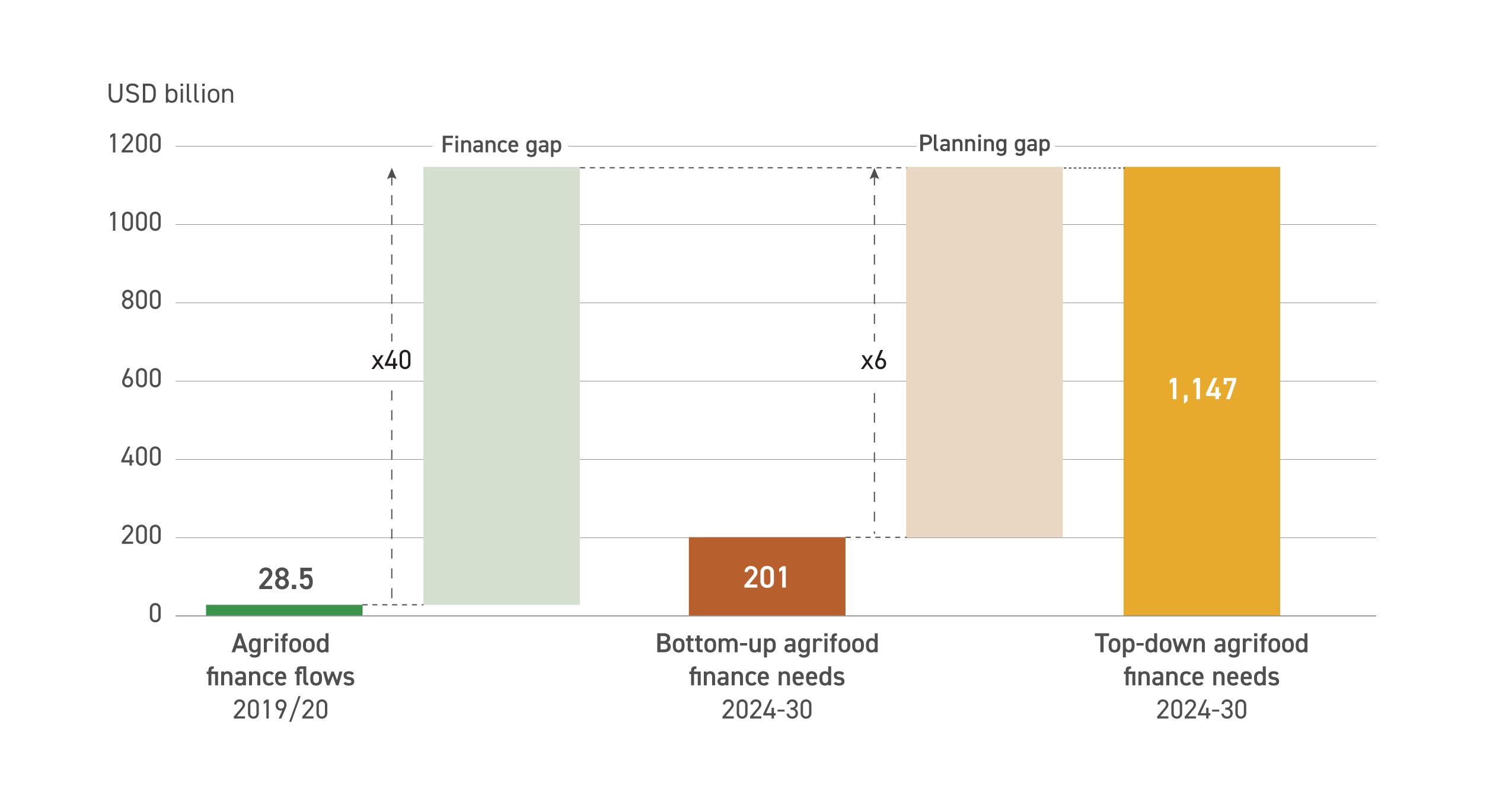

Transitioning agrifood systems to low-carbon, climate-resilient, and nature-positive pathways will deliver significant climate co-benefits. Given their intrinsic relationship with the environment, agrifood systems can naturally reduce GHG emissions, sequester carbon, and restore biodiversity and natural habitats. However, to achieve their adaptation and mitigation potential, the scale of climate investment in these systems must drastically increase. Climate finance flowing to agrifood systems amounted to an annual average of USD 28.5 billion, or less than 5% of total global climate finance tracked in 2019/20 (CPI, 2023).

This report takes a systems-based approach to analyzing the investment needs of the agrifood sector. This goes beyond the traditional agriculture, forestry, and other land use (AFOLU) framework to encompass the entire process of agricultural and food production, from farm, to table, to waste. Agrifood systems also include non-food products (e.g., biofuel, fibers, and timber) that support livelihoods, along with the stakeholders, activities, investments, and decisions involved in bringing products to end consumers (FAO, 2023c). This framework better reflects the complex interactions and feedback loops between the sectors involved across agrifood value chains.

The analysis takes an unprecedented, two-pronged approach to estimating investment needs for global agrifood systems. This dual approach blends the expertise of CPI and FAO to comprehensively understand the gaps between the available, estimated, and required funding to transition agrifood systems to low-carbon and climate-resilient pathways.

- The “top-down” method estimates the level of climate finance required to fund the actions and interventions needed in agrifood systems to limit the average global temperature rise within 1.5°C by 2050.

- The “bottom-up” method estimates the level of climate finance required by countries to achieve their national climate targets for agrifood systems, as stated in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted to the UNFCCC.

A comparison between the top-down and bottom-up analyses reveals three gaps in transitioning agrifood systems: in planning, finance, and data. The two approaches estimate investment needs from different perspectives to understand not only the shortfall in climate finance delivered for agrifood systems at a global level, but also the underestimations from governments about their climate funding needs at a national level. The findings of this “triple gap” aim to inform policy and investment decision-makers about the steps required to transition agrifood systems, especially considering the UNFCCC’s upcoming submission deadline for the next round of NDCs in 2025.

Explore the key insights further by visiting the CLIC website.