State-level renewable portfolio standards (RPS) are a critical part of the U.S. renewable energy policy landscape. 29 states and Washington DC have enacted mandatory RPS policies. Taken together, they require that nearly 10% of U.S. electricity comes from RPS-eligible renewable energy sources by 2020.

But state policy makers have expressed concern about the potential cost of these policies. Over 20 states have included some form of cost limit in their policy. These cost limits are intended to protect electricity consumers from unacceptably high costs, and mitigating this risk can help increase political and public support for the policy. But depending on how they are designed and implemented, these cost limits can have unintended effects: They can increase the cost of deploying renewable energy, make RPS policies more complicated and less certain, and sometimes do not even limit costs as intended.

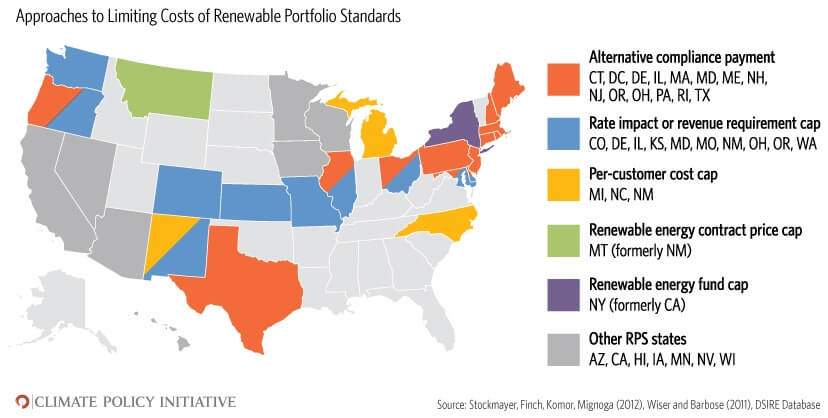

States have taken a wide range of approaches to limiting costs. Common approaches include:

- Alternative compliance payments – ACPs let electricity suppliers meet their renewable energy requirements by making a payments rather than purchasing renewable energy credits or contracting with renewable energy projects. These payments are often used to fund complementary clean energy or energy efficiency programs. The ACP level is usually set by a regulator, and in practice, creates a maximum price for renewable energy credits.

- Rate impact caps – Some states put a limit on how much renewable energy policy can increase electricity rates. These mechanisms vary significantly from state to state in terms of which renewable energy costs are included, how they are calculated, and the time period that they apply to.

- Per-customer cost caps – A handful of states place a limit on the dollar amount any particular customer’s bill can increase because of the RPS.

- Contract price caps – A couple of states have applied limits on the price that a renewable energy generator can contract to sell power to a utility.

- Funding limits – Several states have created limits to the amount of funding that can be used to cover the costs of renewable energy.

CPI has looked at these cost limits, how they work, and the challenges associated with designing and implementing them effectively. Our research identified some key issues that are relevant to a wide range of states with RPS policies: Policy makers and regulators face a range of conflicting pressures. They want to create a clean, reliable electricity system, but protect ratepayers from unacceptably high costs. There is certainly a role for insurance against excessive costs, a “release valve” for the policy if the costs turn out to be much higher than expected. But the devil is in the details. In practice, these cost limits have faced some issues that may make the underlying RPS policies less effective at deploying low-cost renewable power. From the experience of these states, it’s clear that careful design and implementation of these cost limits can make a big difference to their effectiveness. You can read more about cost limits in RPS policies in this this CPI paper, which is focused on options for California.