Indonesia is vulnerable to the climate crisis and the cost of reducing emissions is very expensive at IDR 266.2 trillion per year according to the Minister of Finance, Sri Mulyani.

To mitigate this vulnerability, the Government of Indonesia is formulating a carbon tax, which is aimed at achieving the so-called “double dividend” driving reduced emissions by making it more costly to emit carbon, and gaining revenue to channel towards climate action. When done right, it can achieve a lot more: behavioral change, technology shifts, redistribution of benefits, and an economy-wide renewable energy transition.

This carbon tax is planned as part of a series of environmental economic instruments Indonesia plans to roll out in the coming months. It would also include an emissions trading scheme. The carbon tax has progressed recently, having been incorporated into a draft amendment of the General Taxation Law and received input from the parliament with positive signs towards approval.

While the draft might still go through several rounds of discussion, it has already received a list of responses – unsurprisingly the response from industry groups has been negative. The current iteration states that the carbon tax will apply at the point when an individual or entity (1) purchases a product that contains carbon emissions or (2) reaches the end of a certain period of activity that produces carbon emissions.i It goes on to explain that “products containing carbon includes, but is not limited to, fossil fuels emitting carbon,” and “activities producing carbon includes activities in the energy, agriculture, forestry and land use, industrial, and waste management sectors.” The carbon tariff is proposed to be floating to match the carbon market rate (which for Indonesia’s carbon is currently around USD 5 per ton of CO2e), with a floor no lower than Rp 30 (0.2 cents) or USD 2 per ton CO2e. For perspective, Singapore’s is USD 3.7 per ton, with some criticizing that is too low. Sweden’s carbon tax is considered the highest in the world at USD 126 per ton CO2e.

The application of the carbon tax as drafted is still very broad. It targets both entities and individuals, meaning that it will not be limited to being an upstream tax on, for example, producing refined fuel, but may also be a downstream tax you pay when purchasing fuel from your local gas station. It targets both “products” and “activities,” meaning that there may be a tax on the fuel used to power an airplane, as well as a tax on the trip which is added to the airplane ticket fare. It is open to targeting multiple sectors, meaning that the tax might apply to power plants burning coal, petrochemicals refining oil into plastics, agriculture companies clearing up forests for land, and waste incineration activities, to name just a few.

Key elements for the carbon tax to launch successfully

- Sector prioritization. As the scope is ambitious, it will need to be broken down into a phased approach based on sector prioritization, and the government should lay out a clear roadmap for this. The draft law requires the government to create a “carbon tax and carbon market roadmap” for approval by the parliament. The energy sector should ideally be the first target, given that it is the second largest contributor of emissions, while being easier to implement a carbon tax on compared to the land use sector.

- Complementarity to other environmental policies. While it is important for the government to clarify what sector prioritization might look like, the carbon tax is only one policy instrument in Indonesia’s arsenal of environmental economic policies. It is equally important to iterate how the design of the carbon tax contributes to an overall economic system that drives down emissions and accelerates renewables. In fact, the draft carbon tax policy explicitly states that proceeds from the carbon tax can be allocated to climate programs. The government could iterate the kinds of major climate-resilient infrastructure it expects to be able to finance from the carbon tax proceeds, for example the financing of smart grids for large scale renewable electricity transmission and storage, large scale energy efficiency retrofits for public facilities, or major decarbonization programs beyond the energy sector.

- Pair the carbon tax with benefits elsewhere. Driving down emissions and accelerating renewables may require entirely different policy instruments that work in tandem. For example, a tax on emissions can be pushed out together with a tax incentive rewarding efforts to reduce emissions. A common pushback from industries and the public when it comes to new tax proposals is a familiar demand for “incentives, not taxes.” Essentially, this is asking for carrots without sticks. In reality, carrots and sticks work very well together. In Sweden, the carbon tax rate kept gradually increasing while other tax rates decreased. The marginal income tax rate for individuals was reduced, lowering the highest rates from 80% to 50% percent. The corporate tax rate was lowered from 57% to 30% and other taxes were reformed including the inheritance tax, the entrepreneurial tax, and the wealth tax. This approach has been credited as key in reducing Sweden’s carbon emissions while maintaining solid GDP growth.

- Incentives for low-carbon alternatives. In Indonesia, “carrots” can be offered in the form of tax incentives and tax holidays for households and companies switching to more energy efficient technologies (such as boilers and coolers), installing solar panels, using electric vehicles. Company incentives could include switching from raw materials to less carbon-intensive materials (such as from virgin plastic pellets to recycled plastics). Funds to provide these incentives can be freed up from carbon taxes and can be designed to neutralize any negative economic burden from the carbon tax. Furthermore, such incentives would count towards Indonesia’s climate spending to curb emissions.

Leveling the playing field

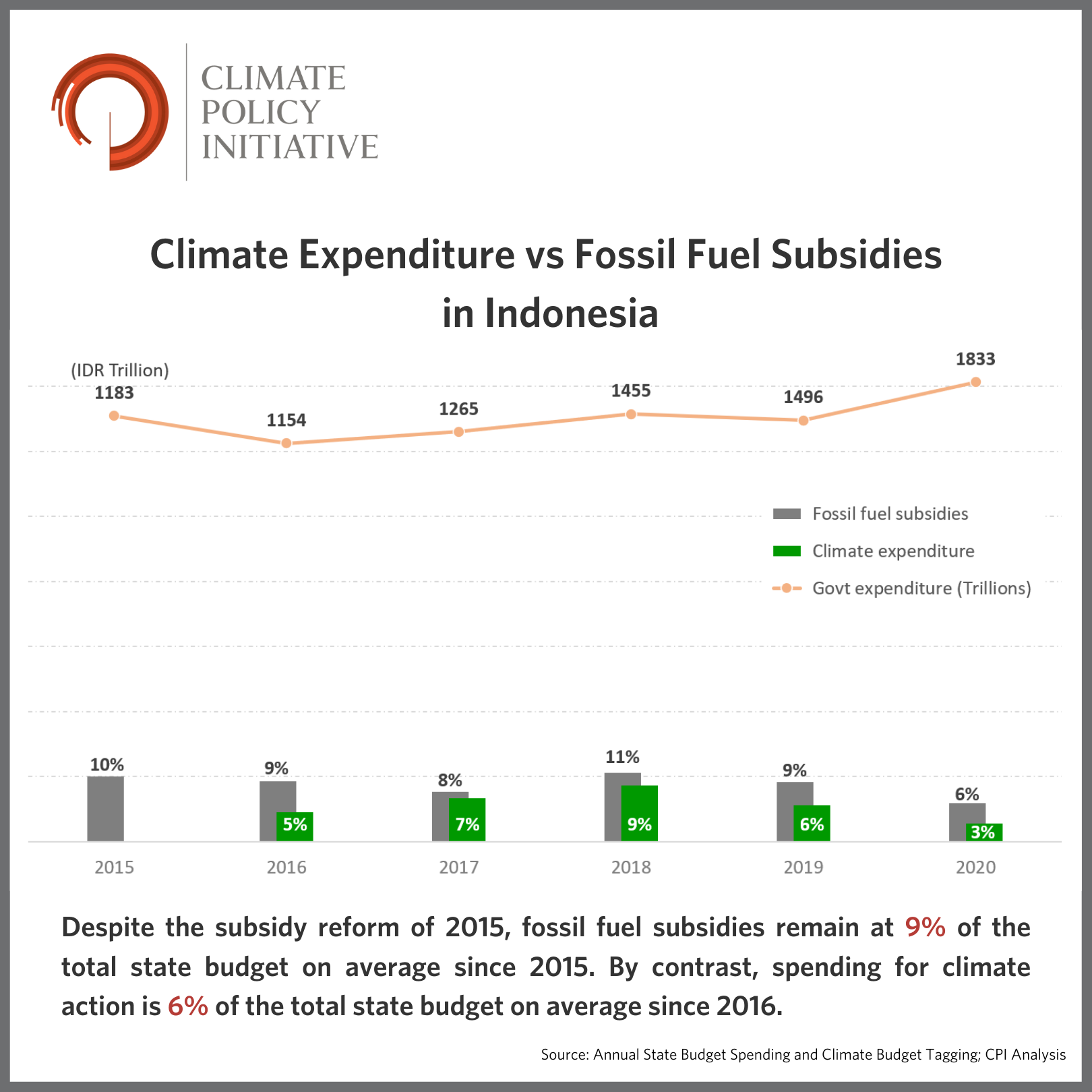

Most importantly, Indonesia should make sure that it does not end up offering carrots to two contradictory goals. Currently, Indonesia still provides subsidies to fossil fuels, namely diesel, kerosene, LPG, and electricity that is largely powered by coal. In fact, the spending for fossil fuel subsidies consistently outweighs the spending on climate activities (See Chart 1). Included here are subsidies provided through PLN, the state electricity company, to allow them to purchase coal at market rates while selling below-market-rate electricity to consumers. As PLN’s actual cost of purchasing coal has been kept artificially low, this has created a significant barrier for renewables to enter the market.

This is among one of the reasons why renewables penetration in Indonesia has been slow, despite the International Energy Agency’s bold assessment that solar panels are now the cheapest electricity in history. “With sharp cost reductions over the past decade, solar PV is consistently cheaper than new coal or gas-fired power plants in most countries, and solar projects now offer some of the lowest-cost electricity ever seen.” ii Unfortunately in Indonesia, the cost of renewables is still high because demand is still low, due to non-market barriers such as pricing policy and other regulatory barriers. Indonesia’s budget spending shows that there is larger support for fossil fuel than there are incentives for renewables. There is no level playing field.

If a carbon tax were applied to a coal producer for every ton of CO2e its coal production emits, it would increase the price of coal. But the increase would not be felt by PLN if the fossil fuel subsidies remain. The state would even have to pay more to cover the gap between the rising fossil fuel price and PLN’s cost. Similarly, a carbon tax on other fuels would not be felt by retail buyers if the market cost is being kept artificially low by government subsidies. This would result in an absurd situation in which the state is paying for its own carbon premiums. Instead, fossil-fuel subsidies should be phased out, the carbon tax applied, and a clear plan should be implemented for the existing beneficiaries of subsidies to receive other, more direct benefits.

The National Planning and Development Agency (BAPPENAS) has already called for a 100% rollback of fuel subsidies by 2030, coupled with a carbon tax, for Indonesia to reach net-zero emissions. If carried out, this would be the biggest subsidy reform since the fuel subsidy reform that took place in 2015. There are also growing calls to transform commodity subsidies into subsidies provided directly to the people, in the form of health insurance premiums, school coupons, electricity tokens, targeted cash handouts, or even universal basic income. The Minister of Finance has stated that the government intends to evaluate these suggestions and “make subsidies more properly targeted.” Many of these, such as health insurance, school coupons, and food coupons, have already been provided. However, there is not yet any formal announcement that the government intends to carry out a full phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies.

Meanwhile, the carbon tax policy discussion is in full swing and is receiving early resistance from industry groups. A fossil fuel subsidy reform might also encounter citizen resistance, as history has shown during the subsidy reforms of 2015, which had gone through several iterations and stoked protest for years. But as history has also shown, significant reforms can be done.

For the government to be successful in rolling out these crucial policies, it must provide a clear vision of the better alternative that will emerge from these policies. It must clearly lay out plans for how the funds freed up from a carbon tax and phased out fossil fuel subsidies—funds essentially obtained from polluters—will be channeled instead into building a prosperous, inclusive, healthy, competitive, and resilient economy.

i This writing is based on Draft Amendment to the General Taxation Law, versions dated 08 June 2021 and 29 September 2021, including Elucidations.

ii IEA World Energy Outlook 2020