Hockey great Wayne Gretzky once said, “I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.”

The same holds true for investing. Those who invest today in the assets that set the world up for a low-carbon, climate resilient future will be the winners of tomorrow.

Last week, California’s legislature passed a bill that will require the two largest pension funds in the United States—CalPERS and CalSTRS, which together manage $476 billion in assets—to divest from coal. Representatives in support of the bill cited both the declining value of coal stock and the need to take action on climate change as reasons to divest.

California’s move is the latest in a slew of recent victories for the divestment movement, which also includes Stanford University, the Church of England, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and Norway’s $890 billion sovereign wealth fund.

The movement’s success has amplified ongoing conversations about the risks of high-carbon assets. But there is more to solving climate change—and to maintaining a balanced investment portfolio—than divestment alone. Accounting for a variety of climate-related risks such as water scarcity, supply chain disruptions, and infrastructure damage, for example, can reduce portfolio volatility while rewarding the most resource-efficient companies in each sector.

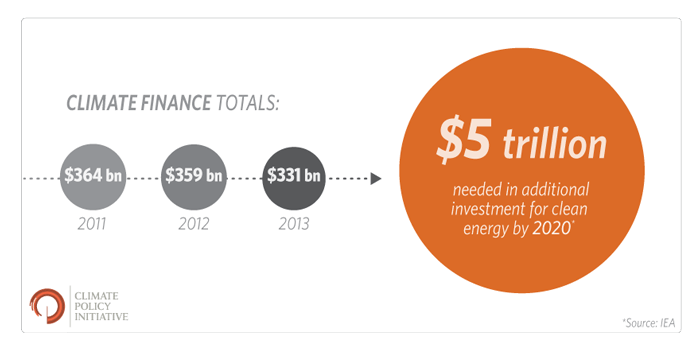

Investment is an equally important piece of the financing conversation. We’re falling further behind the International Energy Agency’s goal of $5 trillion in additional clean energy investments by 2020 to keep temperatures from rising past two degrees (the internationally accepted limit to avoid the most dangerous effects of climate change). However, investors have a variety of emerging opportunities to invest in climate solutions that are good for both the planet and their bottom lines.

A new report from Climate Policy Initiative, an analysis organization that focuses on climate finance, examines this world of risks and opportunities that climate change presents to investors. To add clarity to a complex climate investment landscape, the report explores the data, tools, and financial products available to investors to help manage it.

Climate finance is flowing but it’s not enough. We are falling further behind investment levels needed to reach global temperature targets. So where does data on climate risks and opportunities come from and how useful is it? Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) data is the predominant source of information for investors who want to understand the risks that they face from climate change. ESG information gives investors insight into company performance across climate-relevant factors including emissions, water consumption, energy use, and many other variables. ESG data is incredibly valuable information. There’s mounting evidence that companies and funds that score highly on ESG metrics financially outperform their average- and low-ESG peers. There are several kinds of financial products based on ESG data that allow investors to manage the financial implications of climate change: Other green financial products such as green bonds and YieldCos are growing quickly and deserve exploration. Green bonds are fixed-income securities that link bond proceeds to green activities such as renewable energy or agricultural resiliency. The appetite for them has been enormous. In 2014, the green bond market grew to nearly $40 billion, an increase of more than 160 percent from 2013. But in spite of investor enthusiasm and important efforts to govern green bonds, there is no single definition of what a green bond actually is. It remains unclear whether green bonds are actually raising new financing for climate action or simply repackaging existing corporate bonds. Investors must remain aware of these limitations when considering green bond investments today and support efforts for greater due diligence in the future. YieldCos are publicly traded spin-offs of energy companies that hold long-term, yield-oriented assets such as renewable energy and infrastructure. Renewable assets have very different risk profiles from their fossil counterparts. For example, solar electricity has no fuel costs, and thus is far less susceptible to volatility from changing oil prices. Holding renewable energy and fossil fuel assets separately can price their respective risks better, leading to lower costs of capital while expanding opportunities to invest in renewable energy. However, the more than $20 billion market has been predicated on the belief that parent companies and asset owners will continue to move more and more renewable energy assets into current and future YieldCos. Today’s YieldCos focus on growth and may not meet the needs of all investors; large institutional investors, for example, may seek more stable growth and dividends over time. In short: Green bonds aren’t necessarily green. And YieldCos are probably more accurately described as “GrowthCos.” Neither is perfect, but they both represent an important start. As California adds to the momentum of the divestment movement, investors should keep in mind that investing in climate opportunities is just as important as divesting from risks, but opportunities are currently less developed. To improve this, financial product and service providers can work with investors to create new financial vehicles for green investments and improve existing ones. The $5 trillion clean energy financing challenge demands green investment vehicles that make sense for all types of investors—across industries, geographies, and asset classes. Investors can also lead the way by calling for greater ESG disclosure from companies, by continuing to integrate ESG factors into their investment decisions, and by sharing best practices for minimizing climate risks and maximizing climate opportunities. A version of this blog first appeared in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Overall, ESG-inclined indexes are a promising beginning, and they’re emblematic of the increasing recognition and incorporation of environmental issues within the investment community. Nonetheless, for managing risk, they often lack the levels of transparency needed for investors who are trying to tackle many of the complex risks embedded within their portfolios. And their ability to capture significant long-term green outperformance is not yet clear.