Indonesia’s economy has seen significant growth in recent years, yet wealth remains concentrated and a large part of the population is low income. Access to electricity is part of the solution for bridging this inequality and improving livelihoods. The government of Indonesia has planned for 100% electrification by 2020, but geographic conditions and uneven demand distribution restricts this plan severely, leaving thousands of islands with limited or no access to electricity. This is especially true in the eastern parts of the country.

Decentralized renewable energy (DRE) can increase energy access to Indonesia’s underserved regions and contributes to its National Energy Policy targets. However, existing DRE business models fail to address prevailing barriers in the sector, ranging from policy barriers, limited access to finance, and high investment risks, discouraging private investments.

Decentralized renewable energy (DRE) is a possible solution to accelerate electrification in underdeveloped areas. It is also in line with Indonesia’s National Energy Policy target to achieve a contribution of 23% of renewable energy towards the energy mix by 2025 and the National Determined Contribution (NDC). However, there is a 98% gap in investment per year towards improving Indonesia’s energy system through government funding (CPI, 2018). Therefore, it is a requisite for the Government of Indonesia to attract other sources of finance, particularly from private players, to meet the national clean energy and electrification targets.

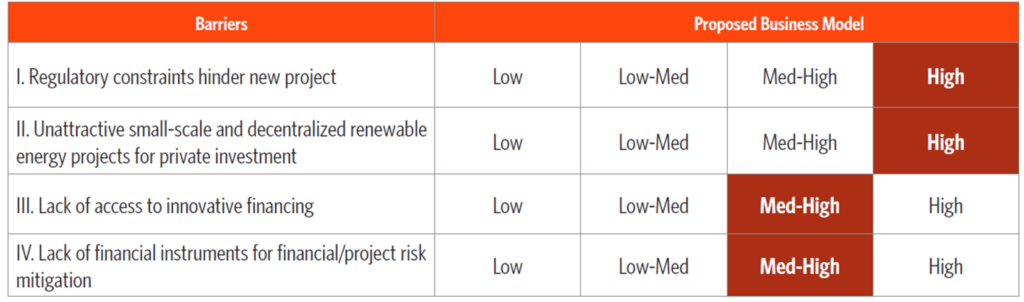

However, there are multiple barriers that make the sector unattractive to private investors, including:

- Regulatory constraints that hinder new projects: Complicated procedures to apply and obtain the business area (Wilayah Usaha) for distribution and sale of electricity, discourage new projects.

- Unattractive small-scale and decentralized renewable energy projects for private investment: Many of the available renewable energy projects are small-scale. Therefore, they are likely to impose a higher unit cost and bring a lower return on investment. In addition, uncertainty on off-taker capabilities is a significant challenge for project developers to secure their revenue.

- Lack of access to innovative financing: Lack of appetite from local banks to invest in renewable energy development and high interest rates on loan services create challenges for developers looking for debt financing. This makes projects financially unfeasible.

- Lack of financial instruments for project or financial risk mitigation: Financial instruments for renewable energy projects are dominated by loans and do not provide the necessary long-term debt financing. Moreover, financial institutions perceive developing clean energy as a relatively high-risk undertaking. To add to this, there are not many financial de-risking instruments available in the market.

Table ES1: Risk level of each barrier faced by private investors in DRE

This report, produced in collaboration with Hivos, aims to improve the overall financial feasibility of the decentralized renewable energy sector in Indonesia. It identifies innovative business models that address the key barriers for private investments by optimizing the existing regulations. The study uses Sumba Island, in East Nusa Tenggara, as an example case.

In order to scale private investment in distributed renewable energy to its potential, policymakers and regulators need to address the sector risks. Policy reform, adopting sustainable business models, and establishing tailored financial instruments, together, can overcome most of these barriers.

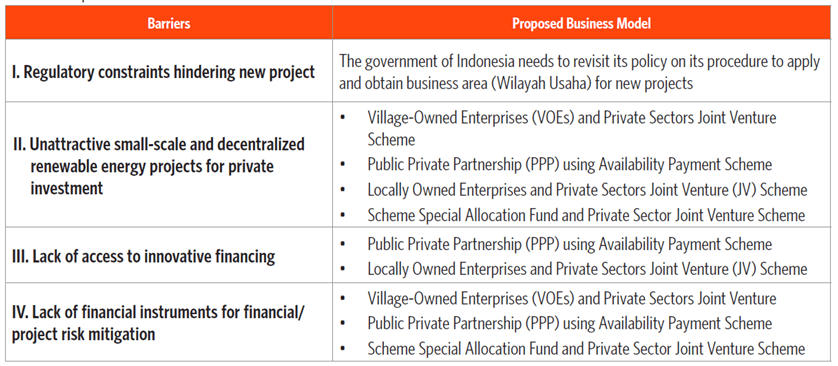

Through our analysis we found that catalyzing private investments for DRE in Sumba and similar islands would require strong commitment and active participation from the government, particularly to enhance its regionally owned enterprises. Capital injections or asset transfers to commission partnerships with the private sector would be key. Further, we found that the first barrier on the regulatory process to obtain a business area (Wilayah Usaha) is the only barrier that the following business models cannot address.

- Village-Owned Enterprises (VOEs) and Private Sector Joint Venture Scheme: This scheme can help address the barrier of off-taker uncertainties since village governments have an inherent understanding of electricity users from their areas. Additionally, the use of capital injection from village funds can potentially reduce the reliability on debt-financing instruments.

- Public Private Partnership (PPP) using Availability Payment Scheme: The use of availability payment schemes can help encourage investments because the regular nature of disbursement from this financial instrument helps maintain the level of public service. Availability payment also ensures return on investment and helps reduce the risk perception of local banks and other financial institutions as these instruments are supported by a long-term government commitment.

- Locally Owned Enterprises (LOEs) and Private Sector Joint Venture Scheme: Direct capital injection into LOEs reduces the need for upfront investment and return on investment. It also reduces the reliance on high-interest loans from local banks and other financial institutions. Moreover, it can potentially address off-taker uncertainties as the renewable energy project will be managed by on-the-ground LOEs.

- Special Allocation Fund and Private Sector Joint Venture Scheme through Joint Operation Mechanism: The special allocation fund is a grant that covers the capital expenses and helps improve the return on investment. The asset will then be transferred to an LOE and be operated by the private sector through a joint operation mechanism to ensure its sustainability.

Table ES2: Maps the aforementioned sector barriers to the business models that can serve as solutions

In addition to implementing innovative business models, pioneering financial instruments would be crucial in addressing some of the investment gaps in the sector. If given adequate business scale, as well as risk and return on private investment, the following innovative financial instruments can complement the business model of each DRE project, thereby addressing the challenges.

- Risk Pooling Investment Schemes: By pooling investments into DRE projects, the scale of the investment value and returns increase proportionately to match the risk appetite of private investors. It can also attract funding from financial institutions as it offers a diverse risk and returns profile.

- Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): An asset-backed security increases the investment scale for DRE by pooling the loan portfolios of multiple projects. It is then sold as a security product to the investors. It can also work as an alternative financial instrument.

- Guarantee Instrument: In small projects, a guarantee can address the security gap because of the tendency to attract small developers with insufficient balance sheets. A guarantee can improve the risk-return profile of a renewable energy project and increase access to long-term funding from financial institutions due to the improved risk profile.

This paper highlights the DRE opportunity in Indonesia, several key barriers for private investment, and the potential paths to address these barriers, but further research is required. Particularly to identify suitable locations to pilot the suggested business models supported by the tailored financial instruments, understand the region-specific barriers to implementation, proof-test the feasibility and replicability of the models, and conduct impact analysis of these solutions. CPI, through its future work, intends to continue to work and delve deeper to actualize these potential solutions.