Executive Summary

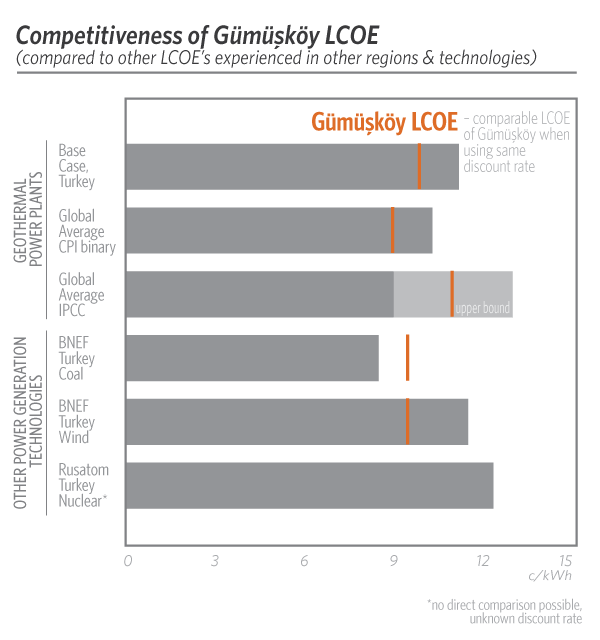

Geothermal energy holds significant promise for the development of low-carbon energy systems. One of the lowest cost sources of renewable electricity, it also has the ability to meet baseload power demand and backstop fluctuating supply from other renewable sources. Geothermal could be a vital component of low carbon electricity systems – where resources allow.

In many countries, early stage exploration and development risks are the main barriers preventing geothermal energy from making a bigger contribution to meeting energy demand. Public finance can help to address these barriers.

Globally, the costs and risks associated with the exploration and development phases of geothermal projects make finding early-stages financing a challenge. Costs related to exploration can reach up to 15% of the overall capital cost of the project, success rates for wells drilled in this phase are estimated at 50-59% (IFC, 2013b), and it takes 2-3 years on average to confirm that a geothermal resource is suitable for generating electricity. Despite this concentration of risk in the exploration phase, 90% of multilateral public finance at the global level has focused on the later stages of the geothermal projects by offering concessional finance to build power plants once the major resource risks have been reduced. Public resources could be more effective when targeting support at geothermal’s early-stage development risks and improving developers’ access to finance.

Turkey is a major growth market for geothermal but could benefit from more private sector involvement in exploration to harness the technology’s full potential.

In recent years, installed capacity of geothermal power plants grew faster in Turkey than anywhere else in the world. The sector went from 30MW in 2008 to 405MW at the end of 2014 – a compound annual growth rate of 54% compared to 4.5% globally – and is well on the way of fulfilling the Turkish government’s deployment targets of 1GW by 2023.

Turkey’s geothermal potential is far higher than its current policy target. Harnessing its full geothermal potential – an estimated 4.5GW of installed capacity – would allow the country to meet 8% of overall demand in 2030 rather than the 1.3% currently envisaged by the government.

Despite this growth, Turkey faces similar issues to other countries seeking to develop geothermal – specifically the ability of the private sector to take on the high risks associated with the exploration and development of geothermal resources. Until 2013, 11 out of the 12 projects developed in Turkey were on sites where the government had already demonstrated that the resource was suitable for generating electricity and then put it out for tender.

While this public-private development model has worked up to now, Turkey is now pushing for more private investment in the energy sector and the government has reduced drilling activity for geothermal exploration. More ambitious policy targets and a transition to a more private-sector led development model could help the sector realize its potential and would fit well with the country’s current policy priorities.

Private sector exploration and public finance in the Gümüşköy Geothermal Power Plant

This case study analyses the Gümüsköy Geothermal Power Plant (GPP) to help policymakers and donors understand which financing instruments and public private financing packages can enable fast and cost-effective deployment of geothermal energy. It is one of a series of studies carried out on behalf of the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) looking at the role of public finance in driving geothermal deployment.

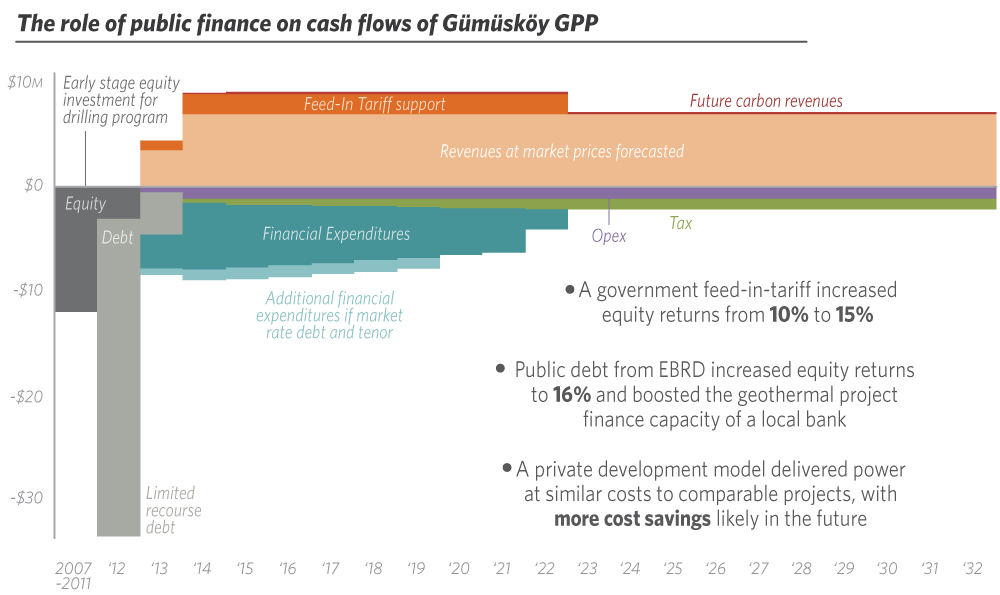

The Gümüşköy GPP is the first case where the private sector financed exploration of an unproven field in Turkey. The 13.2MW project developed by BM Holding, a Turkish infrastructure company, was commissioned in 2013. The company demonstrated significant risk appetite in undertaking early-stage exploration. BM Holding invested up to USD 12m (24% of the total investment costs) in exploration and development prior to financial close, when debt financing of up to USD 34.5m (70% of the total costs) was secured from Yapikredi, a local commercial bank. Yapikredi sourced USD 24.9m of this debt from the Medium Size Sustainable Energy Finance Facility (MidSEFF), an on-lending facility managed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). The Government of Turkey’s provision of a ten-year feed-in tariff ensured the project was financially viable.