Significant knowledge gaps exist when it comes to the climate actions of public finance institutions. While private financial entities’ responses to climate change have received significant attention in recent years, public financial institutions have comparatively received less attention from the research community, stakeholders, and civil society. Recent analyses of public financial institutions have largely focused solely on large Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), particularly Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and a handful of bilateral development banks. Going beyond this subset of public financial institutions is key to understanding how best to align public finance to global climate ambitions.

For example, export-credit agencies (ECAs) have received little attention in the literature and at-large tracking efforts, yet ECAs provide nearly double the international public finance when compared to MDBs. ECAs continue to channel billions of dollars in investment towards fossil fuel projects (Finance in Common, 2021; Macquarie et al., 2020). Moreover, most tracking efforts to date are narrow in scope, focusing only on mitigation commitments, exclusion policies, or implementation actions.

To help close this information gap, CPI developed a taxonomy for tracking finance-related climate commitments and institutional climate strategies covering:

- Paris alignment, net zero, carbon neutral, and other mitigation targets,

- Climate finance and sustainability goals,

- Exclusion and divestment policies, and

- Institutional climate strategies and related implementation actions.

CPI developed an automated data scraping and processing pipeline, utilizing advanced data extraction and natural language processing tools to collect primary and secondary data for the 70 largest public financial institutions: national and subnational development banks, development finance institutions, export credit agencies, mortgage securitization and public housing agencies, and policy banks. Overall, the entities tracked represent 95% of the total assets held by public financial institutions as reported in the Finance in Common dataset of public development banks and development financing institutions, equivalent to USD 20.4 trillion in assets4 (Xu et al., 2022).

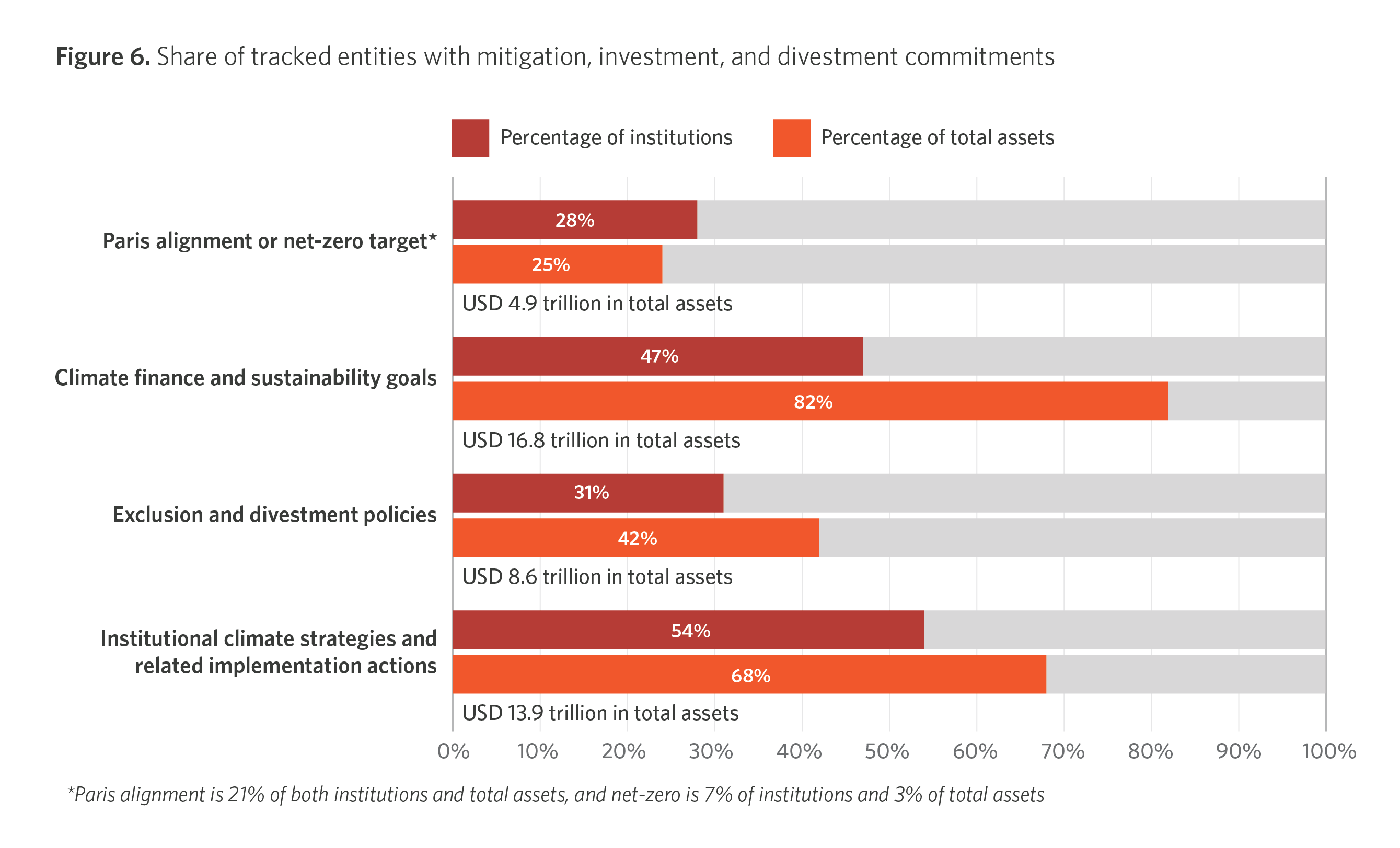

Our findings, as summarized in the chart above, show that, while headway is being made in some public financial institutions, much needs to be done to increase ambition across nearly all public financial institutions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

- Overall, just 20 tracked public financial institutions, holding 25% of tracked assets, have set net zero or Paris alignment targets.

- Outside of the MDBs, very few institutions are making commitments to align their operations and future investments to the goals of the Paris agreement. Where commitments exist, they often lack complementary interim targets or focus only on operational emissions. Interim targets are an integral step towards implementing climate commitments and can be seen as a signifier of commitment credibility (Pinko et al., 2021). The low number of targets specific to portfolio emissions is also significant, as on average 97% of financial institutions’ emissions are in their portfolio rather than in their operations (Lütkehermöller et al., 2020). Tangible results in the real economy are only possible with action to tackle portfolio emissions (Pinko & Ortega Pastor, 2022).

- While 47% of tracked entities have announced climate finance and sustainability goals, these were rarely accompanied by sectoral or geographical specificity. Specificity is key on these targets due to the public sector’s importance in driving finance to sectors that are traditionally less attractive to private capital, as well as regions that are otherwise unable to access capital markets.

- One such sector is climate adaptation. Only six public financial institutions have set climate finance goals that explicitly mention adaptation. All but one, the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development of India, were MDBs. Public financial institutions have a key role to play in closing this gap, yet the lack of clearly defined commitments relating to climate adaptation is concerning. By defining and disclosing adaptation commitments, public financial institutions can signal their intent to respond to growing calls for action in this space.

- Twenty-two public financial institutions have climate-related exclusion and divestment policies of varying breadth and ambition. Only nine included pledges to phase out all fossil fuel financing without exception.

- Public financial institutions have been slow to adopt institutional strategies on climate. Little over half of tracked entities (39 institutions, 55% of our sample) have institutional climate strategies outlining how climate goals will be integrated into the entities’ operations and planning. Most of these institutions operate in an OECD country or globally.

- National and subnational development banks, in particular, are falling behind their peers. While national/subnational development banks make up 37 of the 70 of the entities in our dataset (53%), only nine of them have mitigation targets of any kind, and only nine have announced climate finance goals. Within climate finance goals, only one national development bank, the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development of India, has made commitments specific to climate adaptation finance.

Our analysis identified insufficient accountability measures and lack of guidance from global coalitions and governments as key barriers to credible climate commitments by public financial institutions.

Addressing barriers to climate commitments in public financial institutions is critical. These entities play a key role in closing the climate finance gap, ensuring that international climate finance is deployed in the real economy, building a conducive enabling environment, mobilizing private climate finance, and fostering innovative climate finance mechanisms. By defining and disclosing climate commitments, public financial institutions can signal their intent to respond to growing calls for more ambitious climate action, facilitating future engagement and climate finance flows.