With the objective of assessing major banks’ readiness and progress in disclosing climate-related matters against Indonesia’s sustainability reporting guidelines and international best practices, Climate Policy Initiative has conducted an analysis based on a focus group survey involving commercial banks. Carried out from September 2021 – June 2022, the survey’s sampled banks —national, international, private, and state-owned — represent more than 60% of the market share listed in the Indonesia Stock Exchange. This assessment was then tracked against the Financial Services Authority Regulation Number 51/POJK.03/2017 (POJK 51), which contains ESG parameters for the preparation and reporting of Indonesia’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan.

POJK 51 implements gradual enforcement of Sustainability Reports in accordance with the characteristics and complexity of the business. This began with the banking sector in 2019, issuers and public companies in 2021, and the capital markets starting from 2022. The Sustainability Reporting Guidelines in POJK 51 also include applicability of certain aspects of related international standards, such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The recent initiative of the International Sustainability Standard Board (IISB) to seek feedback on two proposed IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards[1] further heightens the importance of incorporating TCFD recommendations as the climate-focused disclosure benchmark into sustainability reports.

Below are key findings from our assessment of Indonesia banking sector’s sustainability reporting compliance and commitment to disclosing climate-related matters.

WHAT THE NUMBERS SHOW

Between 2019-2021, banks’ ESG portfolio reached 34% of their total portfolio, or USD 3.6 trillion, with most of it directed towards “social” or MSME financing. The regulation requires reporting on 12 sustainable finance activities (11 types of green business and 1 social MSME financing). The way that POJK 51 is currently constructed is grounded in a broader concept of sustainability: comprising societal values related to the environment, governance, and other issues, noting that not all MSME activities are green. On average, more than 70% of ESG finance went to MSME activities, while less than 30% went into green activities. While this is good news for the MSME sector, it also means that there is a potential for higher contribution to other green sectors in Indonesia.

Private banks mobilized a higher portion of green finance than state-owned enterprise banks. Of their total ESG portfolio, private banks channelled 41% into green activities, while state-owned enterprise banks channelled 23%. As state-owned enterprise banks represent a higher market share and volume of financing, an increase in their portion of green finance would be a significant contribution to Indonesia’s climate finance needs.

In the context of climate finance needs, the private banking sector’s contribution has been small. While their green portfolio is on an increasing trend, so far it only contributes 9% of the total investment needs of USD 285 billion in achieving Indonesia’s 2030 climate goals (Government of Indonesia, 2022)[2]: By 2020, the government had funded around 34% of the total financing requirement, leaving the remaining 66% financing gap to be generated from the private sector. OJK estimates the potential of private climate-related investment to be up to USD 458 billion within the period of 2016 – 2030, targeting renewable energy and green building.[3]A 9% commercial bank contribution does not yet come close to OJK’s estimated potential. Commercial banks and other financial institutions can do more, and the right policies should help push their ambition.

WHAT OUR SURVEY SHOWS

Reporting is not an issue, but the quality of reports need improvement. There is 100% compliance with mandatory annual submission of Sustainability Reports from 2019 to 2021, and 83% have met full reporting guidelines in accordance with POJK 51. The remaining 17% provided less detailed disclosure, opting to disregard voluntary reporting guidelines.

POJK 51 disclosure standards could be improved to align with global benchmarks such as the TCFD. Currently, POJK 51 requires high-level sustainability disclosure, while TCFD emphasizes climate-related risks and opportunities. The key disclosures of POJK 51’s sustainability report include:

- Governance

- Strategy through Action Plan Reporting for 1-year and 5-year coverage (Rencana Aksi Kegiatan Berkelanjutan (RAKB)

- Sustainable finance target and commitments

- Implementation of sustainable finance using 11 categories of green finance and MSME finance and performance of other green investment/ financing products, e.g., green bonds (based on POJK 60).

Meanwhile, TCFD targets a more specific and technical disclosure of climate-focused areas. TCFD recommends four climate-focused reporting areas—governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets—with more detailed disclosure, requiring both quantitative and qualitative measures, of climate-related financial risks, exposure, and opportunities to be incorporated into annual report. This means that Indonesia financial sector policy has room to grow and move beyond the disclosure-related obligations to policies that embed climate risks and opportunities directly within the banking and financial system.

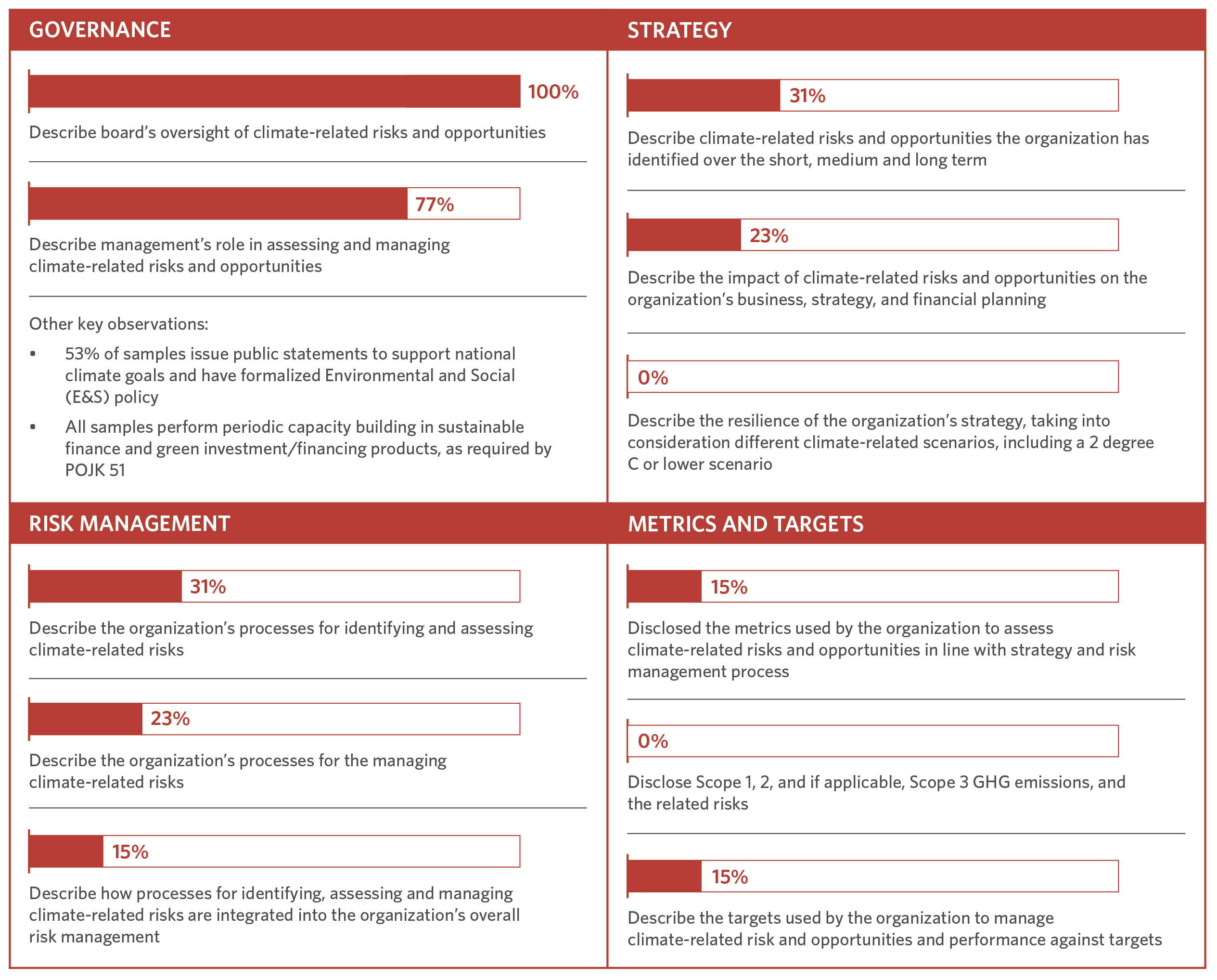

Benchmarked against TCFD recommendations, all banks surveyed are still on a journey towards full climate-related assessment and disclosure. Figure 1 displays the survey results on banks’ readiness to follow TCFD standards:

- In terms of governance, 77% of samples are able describe management’s role in assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities.

- In terms of strategy, only about one third of the samples have identified climate-related impact over the short, medium, and long term on the organization’s business, and financial planning. None of them have assessed the resilience of the organization’s strategy against different climate-related risks and scenarios.

- In terms of risk management, less than 15% have begun processes for identifying, assessing, and managing climate-related risks, integrating them into the organization’s overall risk management, and introducing climate risks as financial risks that will impact their business in the longer term.

- In terms of metrics and targets, although most samples have set clear targets on the portion of green portfolio (i.e., through credit facilities and green bonds/sukuk – as recommended by POJK 51), specific targets, metrics, and performance evaluation in managing opportunities from climate-related risk are still limited. While half of the samples expressed support for a low carbon economy, no commitment has been made for a Net-Zero aligned portfolio. Moreover, metrics and targets on emission reductions remain unclear. Those that have already calculated emissions still limit the scope to banks’ day-to-day operations (Scope 1 and 2 emissions), e.g., electricity, water, and paper savings, and have not covered the investment/ financing products (Scope 3 emissions).

Figure 1. Sampled banks’ disclosure practice benchmarked against TCFD recommendations

To date, climate-related reporting is voluntary, and none of the banks surveyed account climate-related impact as part of their financial statements. Assessing it against the mandatory risk reporting by OJK, such as annual Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP), stress test, semi-annual risk profiling, none of the samples account for climate risk i.e., scope 1, 2, and 3 GHG emission and the related risks. Banks have only assessed and reported 8 conventional banking risks – credit, market, liquidity, operational, legal, reputational, strategic, and compliance – as required by POJK No 18/POJK.03/2016. Meanwhile, in accounting the financial impact of climate risk, none of them account climate-related impact as part of financial statements, i.e., climate risk impact on the measurement of Expected Credit Loss (ECL) as well as valuation of asset, liabilities, and future cashflow based on international standards (IFRS/IAS) or local standards (PSAK). Only 23% of samples cover climate-related matters in notes to financial statements, mainly mentioning management’s consideration on climate change.

THE WAY FORWARD

CPI’s report proposes four main recommendations based on the findings above:

First, improve practicability of regulations. As suggested in our blog on “Indonesia Green Taxonomy 1.0: Yellow Does Not Mean Go”, OJK’s Sustainable Finance Roadmap could be further strengthened through gradual refinement of the country’s green taxonomy to ensure inclusive transition pathways across sectors and interoperability across taxonomies. Indonesia Green Taxonomy 1.0 can be used to assist periodic monitoring of transition progress through enhanced disclosure of green investment and transition pathways (i.e., remedial action plan towards low-carbon transition, the timeline, and its associated cost). While POJK 51/2017 has identified 11 green activities that can be reported, there is an opportunity to widen the categorization under the Taxonomy as it applies a “traffic light” system, namely green for activities with positive impact on the environment, yellow for activities in transition, and red for environmentally harmful activities. There are thus far 15 business activities labelled “green”, 422 “yellow”, and 482 “red”. This is an early step to promote green investment but requires further implementing guidelines for banks, capital markets, and the entire financial sector to get fully on board and deliver on their green investment commitments. For example, the eligibility criteria of investment in the NDC sectors, i.e., energy, AFOLU, industrial, and waste, could be developed in the context of a national climate mitigation target.

Second, enhance governance. Enhance the supervision and oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities within organization through ownership by the relevant Senior Management Function, inclusion of sustainable finance metrics in the organization strategic plans, and continuous capacity building to manage financial risks from climate change.

Third, widen disclosure standards. The clarity and quality of Sustainability Reporting and Green Finance principles could be improved through enhancement of key disclosure requirements of POJK 51 to meet globally accepted frameworks, such as TCFD. Technical guidelines and/or regulation amendments should be further issued to provide clarity for the use of Indonesia’s Sustainable Finance Roadmap, POJK 51, and Indonesia Green Taxonomy 1.0. There is also untapped potential from other sources of finance, making the case to continue widening disclosure requirements beyond the banking sector. For instance, capital markets could be a key driver of greening the financial sector ecosystem. According to data from OJK and IDX, Indonesia’s capital market capitalization from 2015 to August 2022 has reached Rp 9.4 quadrillion, equivalent to 55% of GDP in 2021 or almost 3.5 times the state budget (APBN) in 2022. The year-over-year growth of Indonesia capital market is 18%, compared to only 9% growth in banking finance, making it a source of finance to tap into for green investments.

And last, integrate and streamline reporting. Streamline various regulations and policies in green finance by aligning the common principles in defining, accounting, reporting, and disclosing green activities. For instance, in response to the recently issued Basel III regulatory framework on climate-related financial risks supervisory and reporting, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) has developed a comprehensive global baseline of sustainability disclosures that underline the importance of climate-focused sustainability reporting based on TFCD recommendations. Such streamlining is similarly essential for integrating climate risks and mainstreaming green principles into the overall strategy and risk management framework of Indonesia’s financial sector.

CONCLUSION

Indonesia has made significant progress in creating a roadmap for sustainable finance, supported by an initial regulatory framework that is delivering real impact in mobilizing domestic and foreign investment towards meeting its sustainability goals. And with the announcement of Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) in November 2022, the country is furthering its global leadership in a just transition towards a more green, sustainable, and equitable economy. JETP is Indonesia’s most significant energy transition development to date. It advances Indonesia’s net zero target by ten years to 2050, with power sector CO2 emissions peaking in 2030 — seven years earlier than previous estimate. This commitment is supported by USD 20 billion funding over the next five years, of which USD 10 billion will be expected to be sourced from the private sector. Now that progress is underway, expected adjustments in the regulatory framework, along with greater alignment and ambition from the private sector, will accelerate the momentum we are building.

[1] Drafts of IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information and IFRS S2 Climate-Related disclosure

[2] Government of Indonesia. 2022. Enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution Republic of Indonesia. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-09/23.09.2022_Enhanced%20NDC%20Indonesia.pdf

[3] Bisnis.com. 2022. OJK: Pembiayaan Iklim di Indonesia pada Periode 2016-2030 Bisa Capai US$458 Miliar (OJK: Climate Financing in Indonesia for Period 2016-2030 Can Reach US$458 Billion). https://finansial.bisnis.com/read/20220420/90/1525080/ojk-pembiayaan-iklim-di-indonesia-pada-periode-2016-2030-bisa-capai-us458-miliar