International development partners have recognized Indonesia’s efforts to better meet its climate and environmental goals by pledging their financial support. Indonesia has pledged to reduce 29% emissions by 2030 on its own and 41% with international assistance. However, without adequate delivery mechanisms for climate finance that are capable of navigating the complex arrangements of development cooperation, the collective efforts towards these goals could be ineffective and inefficient.

The Landscape of Public Climate Finance—a 2014 report published by the Ministry of Finance and Climate Policy Initiative—pointed to significant challenges faced by development partners in delivering finance, and by the Government of Indonesia in absorbing international climate finance at scale. A funding mechanism capable of accommodating these challenges is necessary for Indonesia to meet its climate and environment goals.

Recently, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry has established a public service agency (Badan Layanan Umum or BLU) as a non-structural entity under the Ministry of Finance to manage funds for environmental protection and management, including climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. The regulatory framework of a BLU provides solid legal basis for a robust and flexible vehicle to fund activities for public interest, including managing money from international donors.

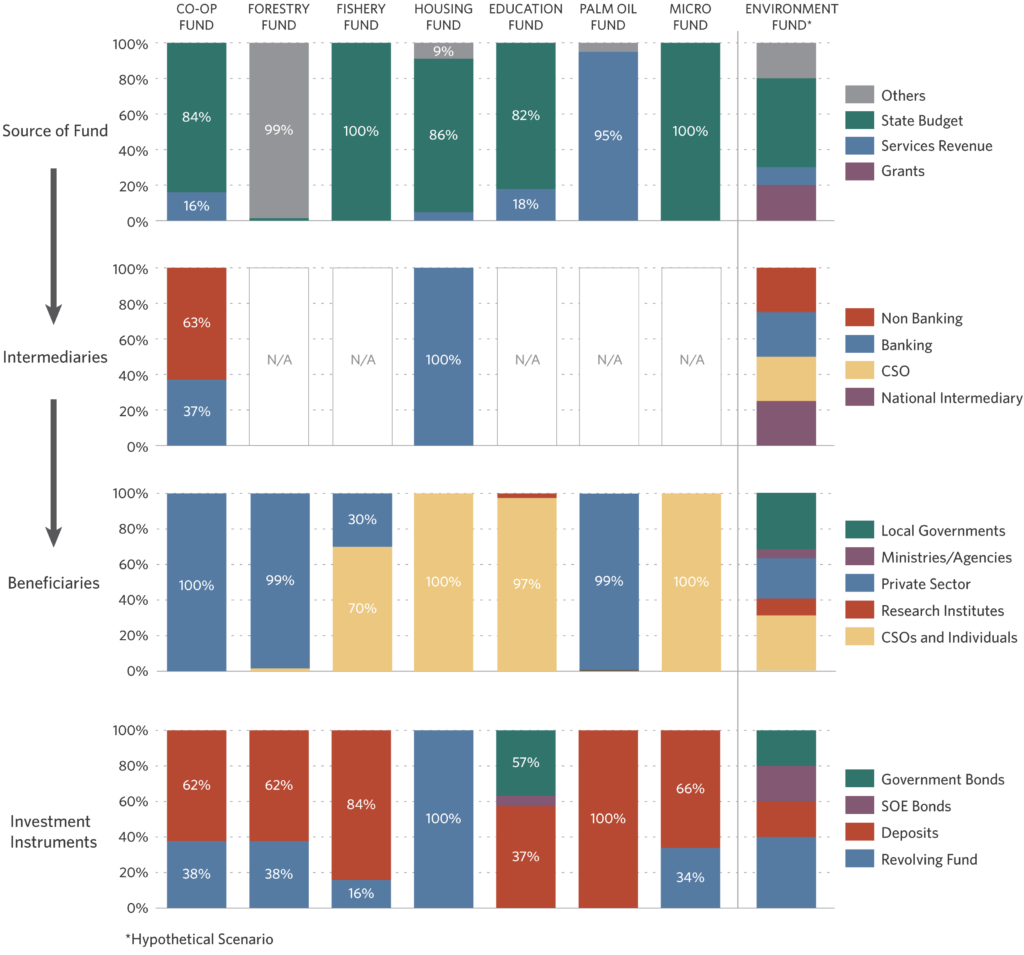

This paper aims to unpack the Public Agency for Environment Fund Management (Badan Pengelolaan Dana Lingkungan Hidup—BPDLH) and analyze its role and potential as the “financing hub” for environmental programs in Indonesia. The analysis is supported by a review of the BLU regulatory frameworks, and includes a comparison with seven fund-managing BLUs already in operation, namely:

- Agency of Revolving Fund Management for Cooperatives and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Bergulir Koperasi, Usaha Mikro, Kecil dan Menengah–LPDB KUMKM) under the Ministry of Cooperatives and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises;

- The Forestry Fund or the Center for Forest Development Financing (Pusat Pembiayaan Pembangunan Hutan—P3H) that is being dissolved to BPDLH, under the Ministry of Environment and Forestry;

- The Fisheries Business Capital Management Institute (Lembaga Pengelola Modal Usaha Kelautan dan Perikanan—LPMUKP) under the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries;

- The Center for Housing Financing Management (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pembiayaan Perumahan—LPDPP) under the Ministry of Public Works and Housing;

- The Palm Oil Fund managed by the Agency for Palm Oil Fund Management (Badan Pengelola Dana Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit –BPDPKS) under the Ministry of Finance;

- Education Fund managed by the Agency for Education Fund Management (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan –LPDP) under the Ministry of Finance;

- The Ultra Micro Financing under the Center of Government Investment (Pusat Investasi Pemerintah—PIP).

In this paper, we also analyze the two funding windows to be managed by BPDLH as it begins its operations, namely the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) Fund and Forest Rehabilitation Revolving Fund.

Comparison of Fund-Management BLUs in Indonesia

KEY FINDINGS

The BLU legal vehicle offers flexibility in terms of the sources of finance it can accept, and the funding instruments it can offer. However, in its current form it requires a dual financial reporting system to manage funding sourced from the state budget and those from other sources. Managing this, combined with the financial risks posed by having various revenue sources and funding instruments that will each require a rigorous risk management strategy, will present a challenge. The good news is that the government is well-rehearsed in these practices due to having managed hundreds of BLUs, seven of which were established specifically to provide fund-management services. The flexibility allows for some interesting managerial traits. Procurement, for example, might follow government procurement guidelines for revenues sourced from the state budget, or it might follow donor guidelines for donor funds managed in trust. BLU regulations also allow BPDLH to look for the appropriate people to manage these challenges by permitting the staffing to involve a mix of civil servant and non-civil servant professionals. Exceptions exist, notably only civil servants can gain access to the BLU treasury as BLU revenue is considered state revenue. This rule upholds the fiduciary standards of a BLU while still being able to attract non-government professionals for strategic or business decisions.

While most sources of revenue for past fund-managing BLUs in Indonesia are from state budgets, BPDLH could have diverse sources of revenue, including revenues from international donors and carbon markets, as well as a diverse project portfolio. Through a rigorous investment and risk management strategy, not only will BPDLH have more secure and diverse sources of funds, but also more diverse beneficiaries. As a result, BPDLH has potential to achieve bigger impacts. That being said, the effectiveness and efficiency of each of the seven fund-managing BLUs varies from each other. Some, such as the Cooperatives Fund, have managed to run its entire mandate and disbursed most of the funds that it manages. Others, such as the CPO Fund, have several mandates but have only managed to disburse funds to a few of them. Since BLUs have a public impact objective as well as a financial objective, effectiveness, and efficiency must be seen through the lens of both, implemented programs and financial performance against impact.

While BPDLH shares the same characteristics with the other fund-managing BLUs in Indonesia on leveraging public and private funds for public services, it is the first BLU with flexibility to source both state funds and international financing. In other words, BPDLH can act strategically as a “funding hub” for various funding mechanisms and act on the principle of additionality by bridging the gap between existing funding mechanisms for various environmental programs. There are various financing gaps that could potentially become the project pipelines for BPDLH, which could be explored as a follow up from this study.