The State of Global Air Quality Funding series, produced in partnership with the Clean Air Fund, maps the outdoor air quality funding landscape, presents major trends in international development finance flows and identifies how — and where — donors can maximize their resources. This analysis helps to build transparency and provides an evidence base for policy makers, funders and campaigners.

The goal is to accelerate progress on clean air and arrest the damage that toxic air inflicts on our health, climate, and economy.

By investing in clean air, donors can save lives. They can also unlock sustainable development and make a liveable planet possible. From investing in a public transport electrification plan in Kolkata, through to supporting South Africa’s transition away from coal-fired power, the report illustrates how donors are already making a difference. Ultimately, these investments pay off, as the U.S. found: with every $1 spent on air pollution control yielding an estimated $30 in economic benefits.

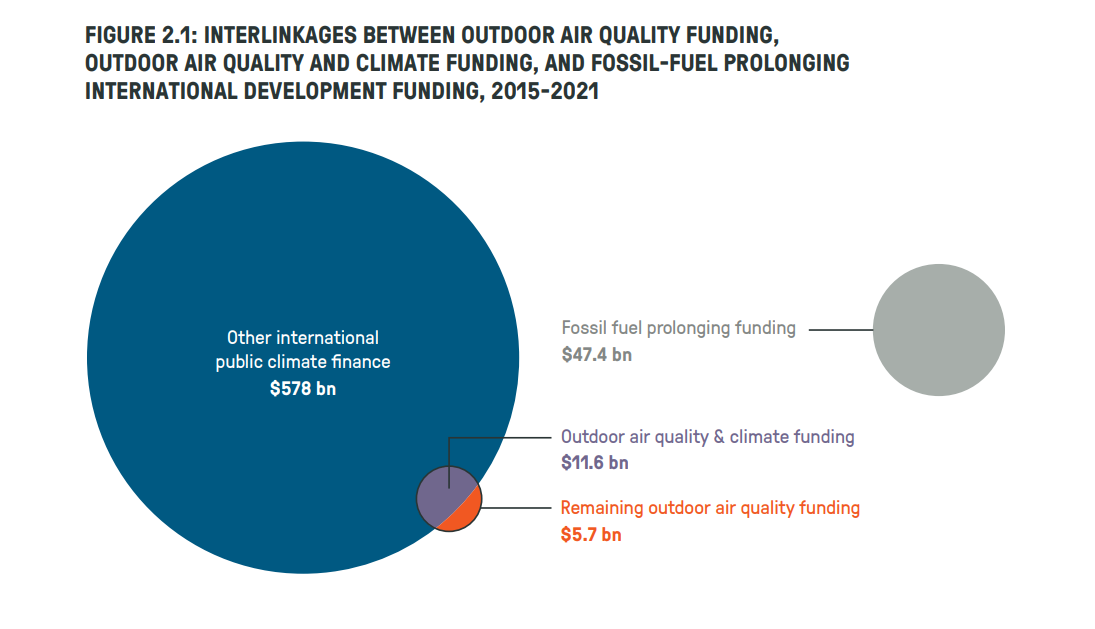

Despite this, too many international donors are still overlooking and underfunding projects that address toxic air. As this report reveals, only 1% of international development funding ($17.3 billion) and 2% of international public climate finance ($11.6 billion) was expressly committed to targeting air pollution over the last six years for which full data is available.

There are signs that the tide is starting to turn.

The data shows a decline in funding for fossil fuel-prolonging projects since 2019. At its peak that year, some $11.9 billion of international development funding was channelled towards fossil fuel projects, threatening both the clean air cause and the delivery of global climate goals. In 2021, for the first time, international development funding for outdoor air quality projects ($2.3 billion) exceeded funding for fossil fuel-prolonging projects ($1.5 billion).

This growing momentum follows the commitment to phase-down coal-fired power at COP26, among other forums. If this trend is to continue downwards, governments at COP28 need to agree on clear strategies for phasing-out fossil fuels completely and transitioning to cleaner energy sources fairly and equitably.

There are several important funding opportunities that donors should be tapping into. Among other gaps, African countries are being left behind and receive only 5% (or $0.76 billion) of all outdoor air quality funding between 2017 and 2021 despite the continent being home to half of the world’s top ten countries with the highest level of air pollution. There are gaps at a city-level too. Accra and Jakarta, for example, are well placed to lead the charge if further climate finance could be mobilized. At a project level, more funding is needed for air quality modelling, measuring and monitoring, which could create greater efficiencies due to better targeting of air quality action, and shore up the public support and political commitment that are necessary for action.

Key findings

- Air quality funding remains too low: Every $1 spent on air pollution control yields an estimated $30 in economic benefits, according to US Environmental Protection Agency. Yet too many international donors are overlooking and underfunding projects that address air pollution. As this report reveals, only 1% of international development funding ($2.5 billion per year) and 2% of international public climate finance ($1.66 billion per year) was committed to targeting air pollution over the last six years for which full data is available.

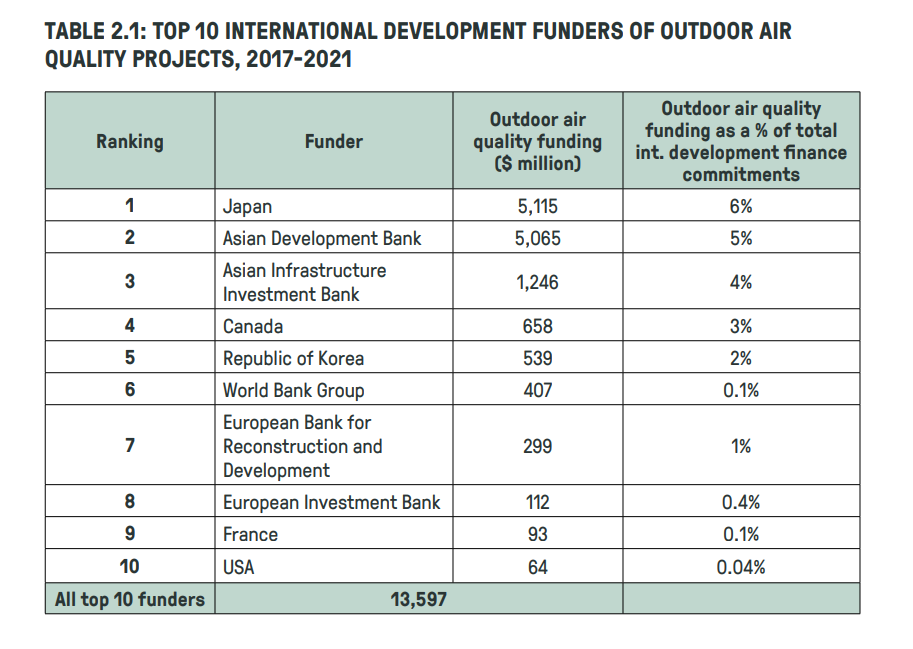

- Top 10 funders tackling air pollution: 10 donors provided 97% of total outdoor air quality funding in the last five years for which data is available. This high concentration of funding between a few funders indicates limited engagement with air quality issues. This funding base needs to be expanded to match the scale of this global crisis.

- Fossil fuel financing overtaken by air quality for the first time: There are signs that the tide is starting to turn on official development assistance supporting fossil fuel usage. The data shows a decline in funding for fossil fuel-prolonging projects since 2019. At its peak that year, $11.9 billion of international development funding was channelled to projects for the extraction and production of oil and gas, threatening the clean air cause and the delivery of global climate goals. In 2021, for the first time, international development funding for outdoor air quality projects ($2.3 billion) exceeded funding for fossil fuel-prolonging projects ($1.5 billion).

This suggests growing momentum following the commitment to phase down coal-fired power at COP26. Since then, 34 countries and five public finance institutions agreed to stop international public finance for fossil fuels by the end of 2022. If this trend continues downwards, governments at COP28 need to agree on clear strategies for phasing out fossil fuels completely and transitioning to cleaner energy sources fairly and equitably.

- Untapped opportunities: climate finance and financial instruments: Only 2% of international public climate finance explicitly tackled outdoor air pollution. The causes and consequences of climate change and air pollution are interconnected, and so are their solutions. It is critical to track the benefits of climate interventions on air quality. Monitoring local air quality benefits – particularly in relation to health – can help to deliver a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of global climate interventions, allowing for more informed decision-making and resource prioritization.

There are a range of financial instruments available to funders with the potential to incentivise and catalyse more funding towards air quality projects. Unharnessed finance vehicles like green bonds, social bonds and results-based funding can create efficiencies and mobilize long-term private capital into air quality projects. So smarter use of these financial instruments by government, international development funders and private investors will catalyze further investment, as the risk is shared. - Loans prioritized over grants: 92% of outdoor air quality funding was provided in the form of loans ($12.9 billion), of which $5.3 billion was low-cost/concessional. Concessional funding is particularly important for low- and middle-income economies who may already be burdened with high debt or are in a debt crisis in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Grants accounted for the remaining 8% of outdoor air quality funding committed in the period, largely from governments (93%). Such funding is vital for facilitating capacity building and technical assistance. Action on air pollution is ultimately a public good and may not develop without the catalytic role of grants. Recipients also favour grants as they avoid worsening debt positions and provide local authorities with more choice in spending.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUNDERS

We recommend a substantial increase in the volume of funding for air quality from OECD-DAC donors, whether channelled through multilateral channels or bilaterally. The report urges funders to better incorporate air quality co-benefits into climate and health projects. Priority should be given to increasing grant and concessional finance and to ensuring that funding reaches all countries and regions in need. This is particularly important in the context of the debt distress faced by so many countries that receive international aid.

As the largest funders of outdoor air quality projects, Multilateral Development Banks can play a critical role in substantially increasing the availability of development finance for air quality. There is a particular role in driving this agenda for the World Bank, whose new leader, Ajay Banga, has made access to clean air an explicit part of its remit.

National policy makers and regulators are encouraged to track and report on government

spending on air quality to increase transparency and assess progress over time. This includes capital obilised from other sources for projects with air quality co-benefits. For example, private capital could be attracted at scale through innovative financial vehicles such as Shari’ah-compliant bonds or sukuks and structured finance mechanisms such as securitization.

Ultimately, funders and policy makers need to rewrite the script. They must reassess how they finance climate and air quality projects in tandem if we are to live up to the hopes of the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals. Only then will we see the funding scale up to match both the size of the opportunity and the scale of this pervasive, global problem.