Executive Summary

As Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) design a post-2020 climate agreement and establish their national contributions within it, the question of progress toward existing climate finance targets has become a sticking point. While mobilizing $100 billion will not meet the climate investment challenge by itself, the goal is currently the primary political benchmark for assessing progress on climate finance. This paper aims to make a positive contribution in the lead up to Paris by first unpacking the key variables Parties have emphasized in debates about “what counts”, and then proposing an approach to classifying climate finance that Parties could use as a starting point for their analyses and interpretations. It takes no position on what should count towards the $100 billion: instead it organizes different aspects of climate finance in politically relevant ways that could help facilitate clearer understanding and convergence.

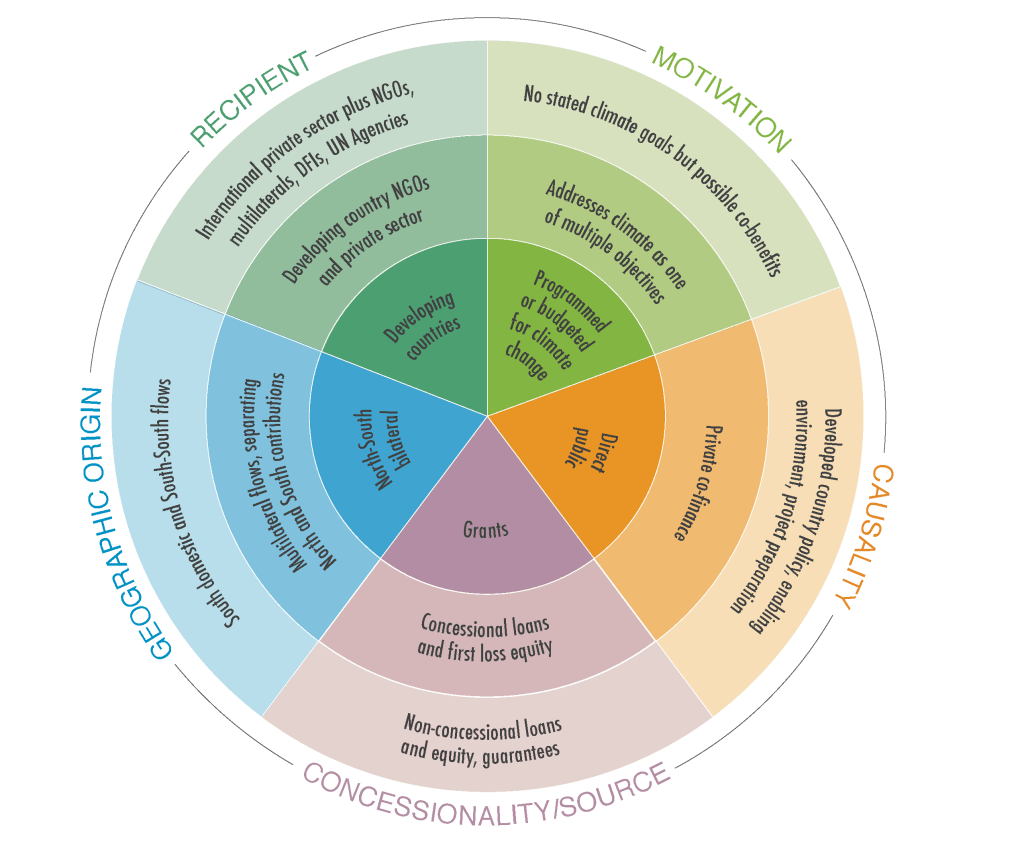

This paper builds on existing work by Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), Overseas Development Institute (ODI), World Resources Institute (WRI), and others including the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance on mapping and tracking the landscape of climate finance. It distills the debate into five key variables that have emerged as relevant to what Parties consider to “count” as climate finance:

- Motivation – the extent to which a financial flow was explicitly designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or support climate adaptation.

- Concessionality / source – the legitimacy of public versus private sources of climate finance, and the degree of “softness” of the finance reflecting the benefit to the recipient compared to a loan at market rate.1 To simplify categorization and facilitate debate we combine “source” with “concessionality” in this paper, though we recognize this is an imperfect conflation.

- Causality – the extent to which a contributor’s intervention (whether public finance or policy) can be said to have mobilized further investment in climate-relevant activities.

- Geographic origin

- Recipient

Each of these variables is explored in depth in section 4 of the paper. In all the diagrams used to represent them, different categories are organized into concentric circles according to political consensus (what we refer to as “onion diagrams”). The closer a category is to the center of the onion diagram, the more notional consensus there is among stakeholders that it should count toward the goal. The key issues considered are summarized in the figure below.