What is the Rural Credit Policy?

Rural credit is the main instrument used for financing Brazilian agriculture. Related re-sources and lines of finance are determined in the Agricultural Plan, announced annu-ally by the federal government. Some credit lines offer special conditions for low-carbon crops and other sustainable practices. The Agricultural Plan is capable of fosteringsustainable practices in rural areas through the adoption of finance criteria and incentives associated with climate mitigation and adaptation objectives. These in-centives can promote low-carbon agriculture, as in the case of the credit line of the Program for Financing Sustainable Agricultural Production Systems (Programa de Financiamento a Sistemas de Produção Agropecuária Sustentáveis – RENOVAGRO), or resilience to climate change through specific planting techniques such as no-till farming.

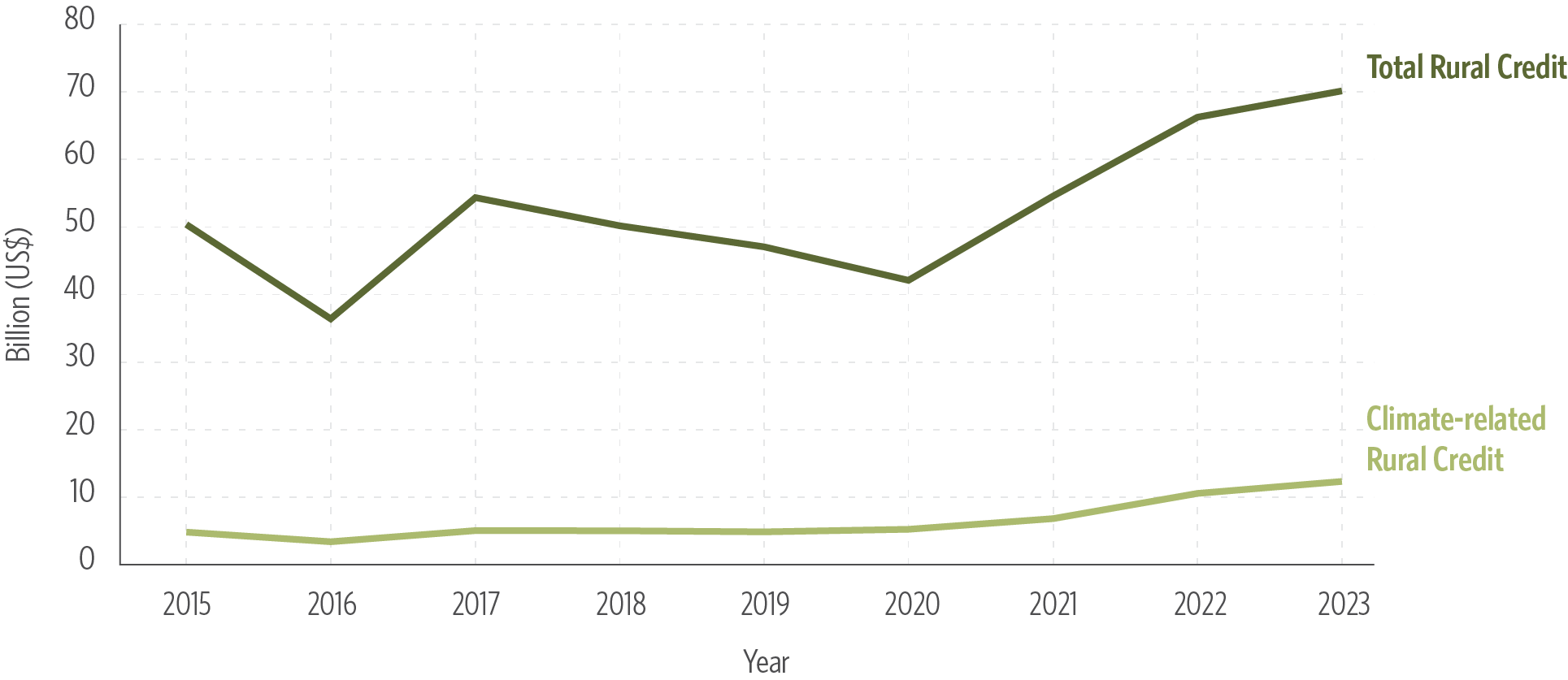

Rural credit was the instrument tracked as having the largest volume of climate finance for land use in Brazil between 2021 and 2023, at an average of US$ 9.9 billion per year. However, this figure represents only 16% of total rural credit operations in the country during the period, which averaged US$ 63.7 billion per year. Figure 4 shows the evolution of total rural credit, as well as rural credit classified as climate-related, between 2015 and 2023.[1]

Figure 4. Evolution of Total Rural Credit and Climate Credit, 2015-2023

Note: Evolution of total rural and climate credit for the purposes of funding, investment and industrialization. The marketing purpose was not included.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO with data from SICOR/BCB (2023), 2024

The growth in climate-smart rural credit reflects not only an increase in resources earmarked for sustainable practices but also changes in transaction records. The criteria for classifying rural credit as climate-relevant follows the provisions of the BCB’s Public Consultation no. 82. No-till farming account for 40% of the growth in climate-smart rural credit between 2019 and 2024. This agricultural practice was not registered in the Rural Credit and PROAGRO Operations System (Sistema de Operações do Crédito Rural e do PROAGRO – SICOR) until 2018, though it was widely used for crops such as soybeans, corn, and wheat. However, between 2021 and 2023, US$ 2.2 billion—or 23% of tracked rural credit—was categorized as climate credit solely because it was recorded in SICOR as no-till farming. This represents 13% of the total flows tracked for the period covered in this report. Therefore, part of the growth in rural climate credit reflects a change in database classification, rather than an increase in the allocation of resources to sustainable practices.

In addition, it is important to note that registration with SICOR involves no effective verification mechanisms. With the increase in discourse on sustainability in agriculture and its relationship with the credit agenda, the declaration of no-till farming has come to be viewed as a benefit, prompting a significant increase in registrations. This growth, therefore, may reflect producers’ greater interest in reporting this practice.

Furthermore, the term “no-till” covers a range of practices, and a better disaggregation of which of these have additionality from a climate perspective would be beneficial. Several national and international initiatives have sought to establish sustainability parameters applicable to the land use sector. While some of these initiatives focus on classification and monitoring, others have the broader objective of directing finance towards sustainable production. A detailed tracking and analysis of the intersections and complementarities between these initiatives is available in a report published by CPI/PUC-RIO (Oliveira et al. 2024). The Brazilian Sustainable Taxonomy—currently under development by the Ministry of Finance in partnership with other ministries, regulatory agencies, the private sector, academia, and civil society organizations—could offer more precise and transparent sustainability criteria for categorizing rural credit.

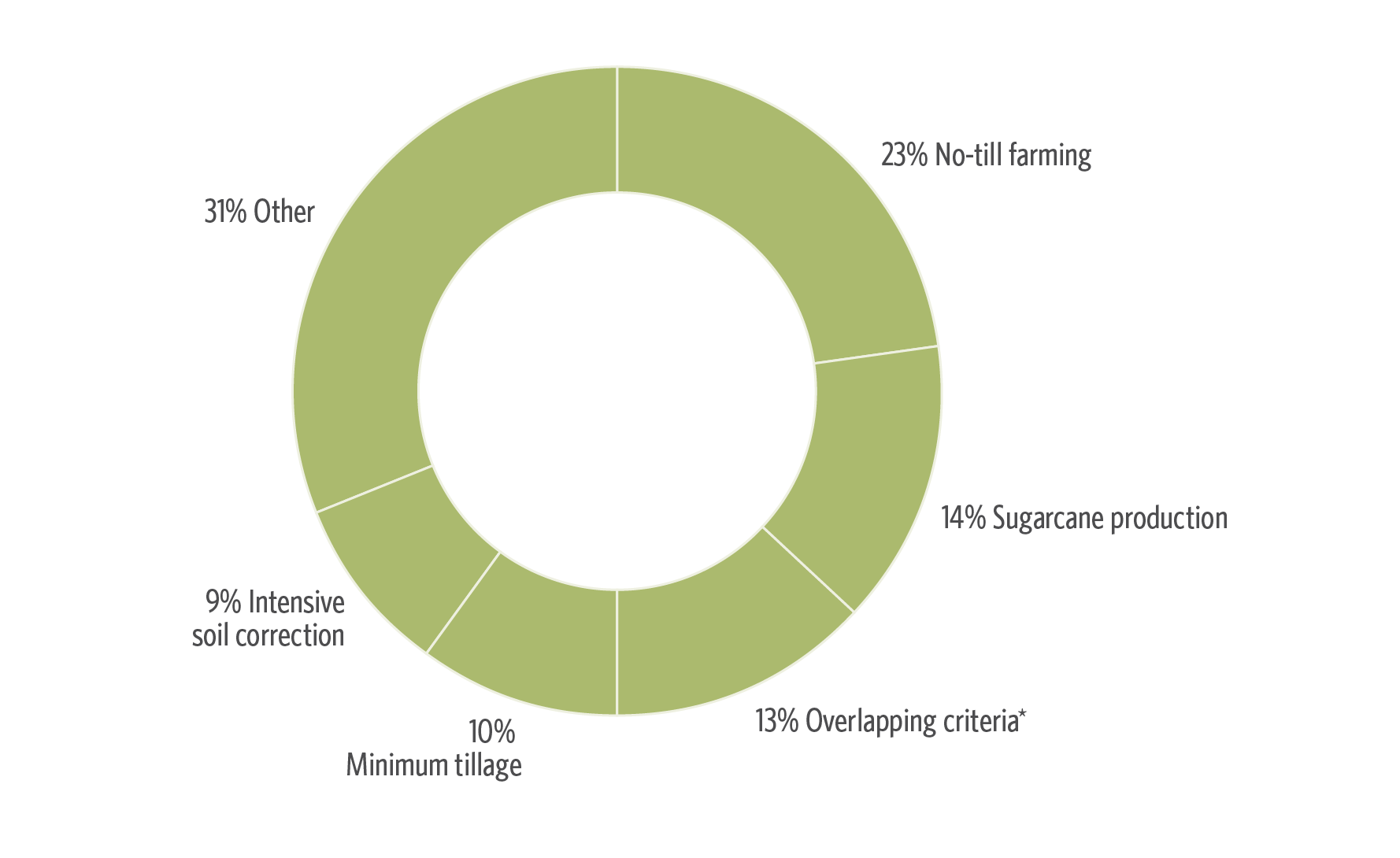

What Makes Up Climate Rural Credit?

The Central Bank’s Public Consultation no. 82 of 2021 suggested sustainability criteria applicable to rural credit, using information on products, planting methods, and techniques adopted. The most relevant criteria between 2021 and 2023 are no-till farming, intensive soil correction, minimum tillage, and sugarcane production, which together account for 69% of tracked climate rural credit (Figure 5).

In particular, all sugarcane production is considered sustainable because it is associated with the production of biofuels, as per the criteria of Public Consultation no. 82. This criterion alone is responsible for the inclusion of US$ 1.4 billion per year, corresponding to 14% of rural climate credit.

Figure 5. Climate Rural Credit Criteria, 2021-2023

Note: Overlapping criteria refers to rural credit associated with two or more criteria, among them direct planting, sugarcane, minimum tillage, and intensive soil correction.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO with data from SICOR/BCB (2023), 2024

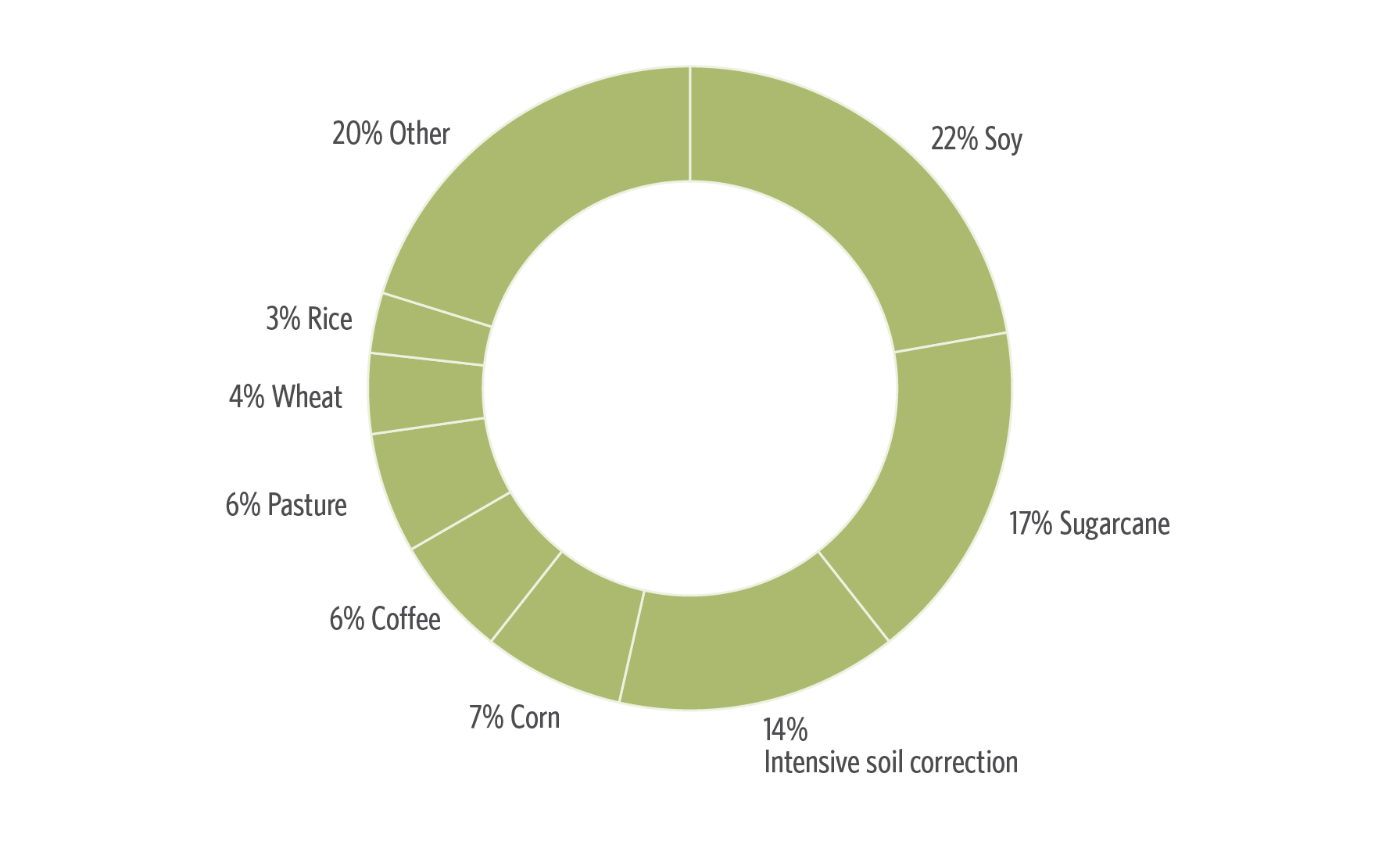

Soy is the main product benefiting from climate rural credit, receiving US$ 2.2 billion per year, or 22% of the total tracked (Figure 6). Despite its significance among climate flows, this figure represents only 16% of the total rural credit for soybeans. The classification of soybean production as climate-relevant is due to the planting techniques used: no-till farming is the main reason, accounting for 75% of the rural credit tracked for this product, followed by minimum tillage and agro-sylvo-pastoral systems.[2]

Figure 6. Climate Finance via Rural Credit by Product Financed, 2021-2023

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO with data from SICOR/BCB (2023), 2024

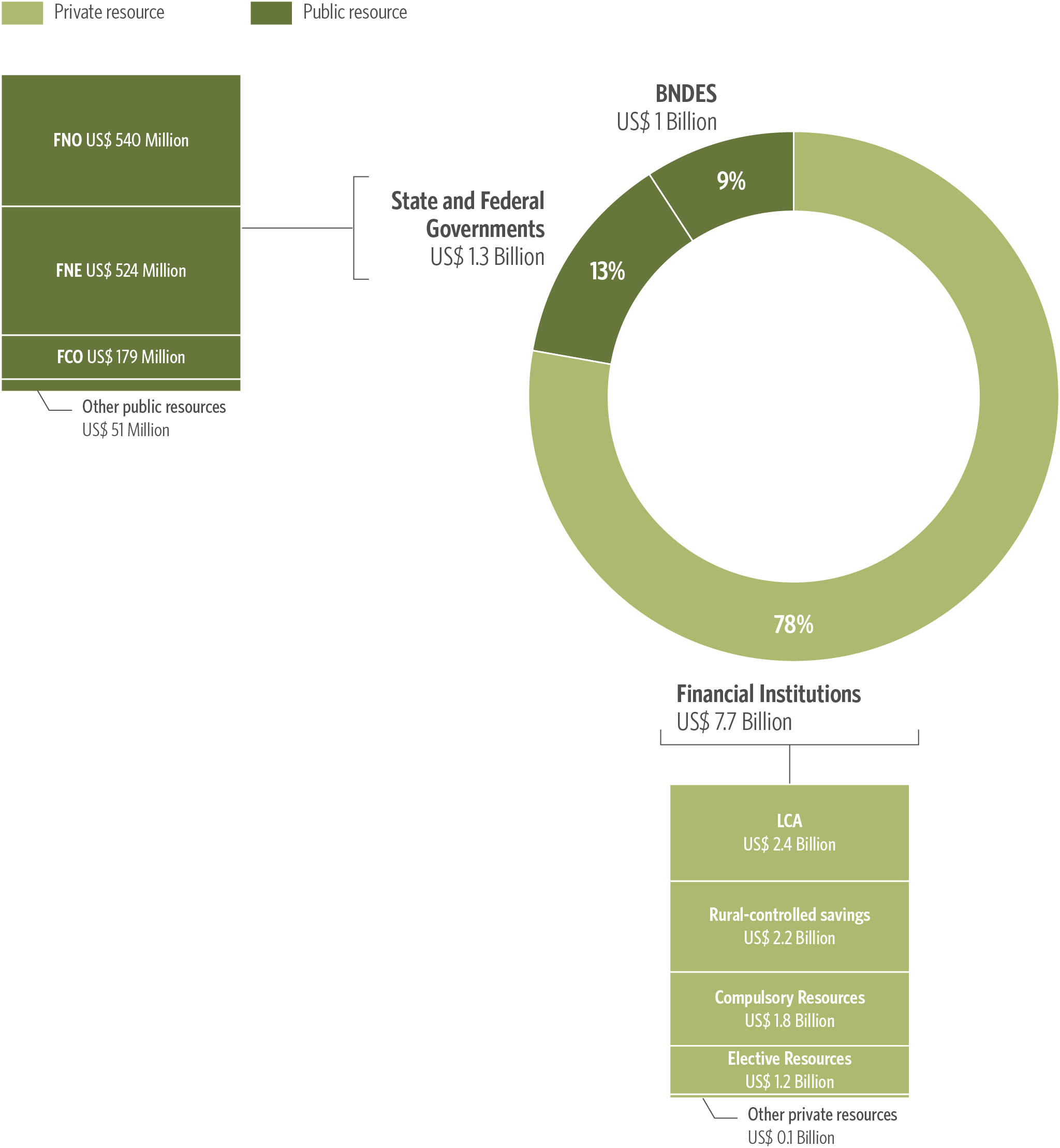

Private resources make up 78% of rural credit aligned with climate objectives, totaling US$ 7.7 billion per year, from financial institutions such as private and public banks and credit cooperatives (Figure 7). These resources are directed by the federal government’s credit policy, which determines both the allocation and the conditions of finance. Therefore, these flows do not follow the usual market mechanisms. The Agricultural Plan is the main instrument of this policy, annually establishing a set of rules for agriculture finance, including the obligation to allocate part of current account and savings account resources to rural credit.

Figure 7. Climate Finance via Rural Credit by Source of Funds, 2021-2023

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO with data from SICOR/BCB (2023), 2024

In the 2023/2024 Agricultural Plan, there was an important change, making it compulsory to direct the funds raised through Agribusiness Letter of Credit (Letra de Crédito do Agronegócio – LCAs) to rural credit operations from 35% to 50% (MAPA 2023). As a result, LCAs became one of the main sources of climate resources over the period covered by this report, with US$ 2.4 billion per year, or 24% of tracked credit.[3]

Finance from public resources amounted to US$ 2.4 billion per year, representing 22% of the total tracked for rural climate credit. The BNDES is an important financier of rural climate credit, with 9% of the flows tracked (US$ 0.9 billion per year). The federal government was responsible for 13% of the flows, with finance coming from the Constitutional Financing Fund of the North Region (Fundo Constitucional de Financiamento do Norte – FNO) (US$ 540 million per year), the Constitutional Financing Fund of the Northeast Region (Fundo Constitucional do Nordeste – FNE) (US$ 524 million per year) and the Constitutional Financing Fund of the Midwest Region (Fundo Constitucional de Financiamento do Centro-Oeste – FCO) (US$ 178 million per year).

A crucial issue is the need to measure the impacts of climate finance flows on the sustainability of crops and the reduction of GHG emissions. The ABC Recuperação credit line, which is the main instrument implemented in recent years for the recovery of degraded pastures in Brazil, has been found to have very limited effectiveness (Oliveira, Souza and Assunção 2024). Use of the credit does not generate a significant increase in the overall quality of pastures and causes very marginal changes in land use.

Another relevant consideration is how to ensure that climate finance flows generate economic incentives that promote sustainable agriculture and forest preservation in an integrated manner. An analysis of the subsidized rural credit granted to properties that deforested between 2020 and 2022 indicates that 31% of those that deforested accessed subsidized credit, totaling an average of R$ 14 billion (US$ 2.8 billion) per year (Mourão, Stussi and Souza 2024). This suggests that credit for sustainable practices, such as the direct planting of soybeans, may also be benefiting properties that deforest.

[1] The data for rural credit in this report only considers the purposes of funding, investment and industrialization, disregarding the purpose of commercialization. Rural credit for commercialization purposes was excluded from this analysis and from the calculation of the total amount of rural credit granted over the period, as it can be used to finance the purchase of products through the Minimum Price Guarantee Policy or for refinancing, such as discounting Rural Duplicates (Duplicata Rural – DR) and Rural Promissory Notes (Nota Promissória Rural – NPR). The annual average of rural credit granted considering all purposes—funding, investment, industrialization, and commercialization—was US$ 73.7 billion per year for the period 2021 to 2023.

[2] This report considers only the purpose of commercialization.

[3] An LCA is a fixed-income security issued by financial institutions to finance agribusiness through loans to rural producers, created by Law 11.076 of 2004 (B3 2024).