Under President Obama’s recently announced Clean Power Plan, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed that states cut greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants by 30 percent from 2005 levels.

Commenters on both sides of the aisle say this rule means big changes for the coal industry.

But before we get fired up about the changes, it’s important to take a look at the facts: While states will need to retire coal plants at the end of their useful lives to meet the proposed limits, EPA’s rule would give states a great amount of flexibility to avoid coal asset stranding and still meet emissions reduction targets. In fact, valuing the right services from coal plants will prove the more important question for a low-cost, low-carbon electricity system.

Let’s look at why.

First, we need to understand what the rule really means for coal asset stranding. An asset is “stranded” if a reduction in its value (that is, value to investors) is clearly attributable to a policy change that was not foreseeable by investors at the time of investment.

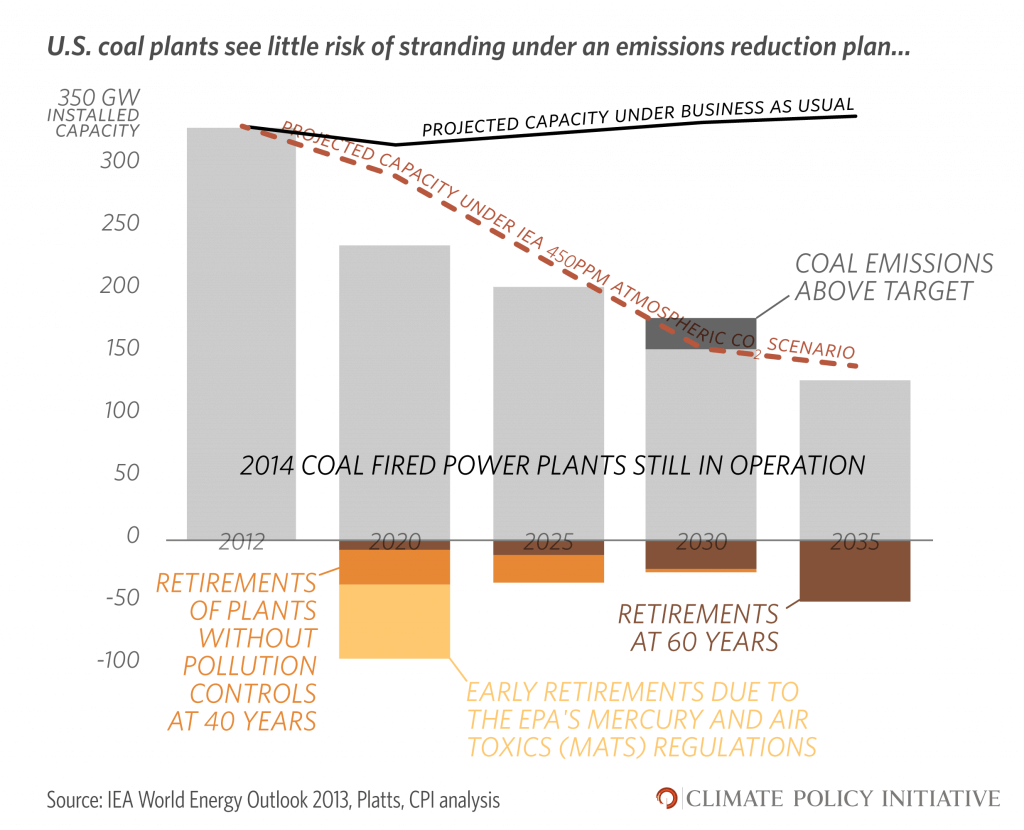

In our upcoming analysis of stranded assets, Climate Policy Initiative finds that if no new investments are made in coal power plants and existing plants retire as planned (typically, 60 years for plants with pollution control technology investments and 40 years for plants without), the U.S. coal power sector stands to experience approximately $28 billion of value stranding from plants that are shut down. While that’s a big sounding number at first glance, it’s very small relative to the size of coal power sector. As the figure shows, that retirement schedule puts the U.S. coal power sector on track to come close to the coal power capacity reductions called for in the IEA 450 PPM scenario to limit global temperature increase to 2°C.

This means that if EPA’s regulations leave room for existing coal plants to retire at the end of their useful lives, the country can achieve needed emission reductions from the coal power sector with minimal stranding. EPA’s proposed rule provides the flexibility to do just that. EPA sets a CO2 emissions rate standard for each state’s aggregate pool of fossil-fuel plants, but the states decide how to dole out responsibility for the emissions reductions across fossil fuel plants, renewable generation, and energy efficiency efforts. And states can determine the timing of reductions as long as they meet their emissions rate standard averaged over 2020 to 2029. States can use this flexibility to avoid forcing coal plants to make new investments, thereby enabling most coal plants to retire on time without stranding value. So, we’ve established that the rule provides the flexibility to meet state targets without the asset stranding feared by some, but what changes are in store for coal? In many states, it will be about focusing on ways to value the “right” services from coal plants. Many states will look to renewable energy as an attractive way to meet emission rate standards. As wind and solar play a greater role in our electricity system, we will need balancing services to fill electricity supply gaps left by intermittent sunlight and wind. It will be crucial that balancing power sources can ramp up or down quickly according to demand. Depending on the region, these power sources may include hydropower, natural gas-fired plants, storage technologies — or certain coal plants. Coal plants that do stay online will need to play new roles. Instead of base load generators, they should be valued as reliable backup power. In the end, those coal plants kept online for balancing services may run at lower generation levels with higher emissions rates in order to achieve greater net emissions reductions across the system. However, utilities and regulators will need to adopt new business models that facilitate this transition. Without business models and policy that value coal plants appropriately, the $28 billion of coal plant assets at risk of stranding will grow. It is up to the states to understand how electricity business and market structures will evolve and then develop a plan that appropriately values reductions, generation, and balancing to facilitate the lowest cost pathway to meet EPA’s standards. EPA’s rule gives states the opportunity to do this, but it will not guarantee that the country takes the lowest-cost path to a low-carbon electricity system. It’s now time to put our heads together to help states meet this challenge. — Andrew Goggins, an analyst at Climate Policy Initiative, also contributed to this piece. This piece originally appeared on The Huffington Post.